Though some American settlers had traveled to Oregon and California in the 1830s, West-bound wagon trains really started heading out in great numbers in 1843, when Oregon’s Provisional Government began promising 640-acre tracts of land to each white family that settled in the territory.

It was 2,170 miles from Independence, Missouri to Oregon City, Oregon. The trip took four to six months. Oregon-bound travelers were advised to keep their wagons weighing less than one-and-a-half tons fully loaded. A new wagon and spare parts, which were almost always needed, would cost a family close to $100.

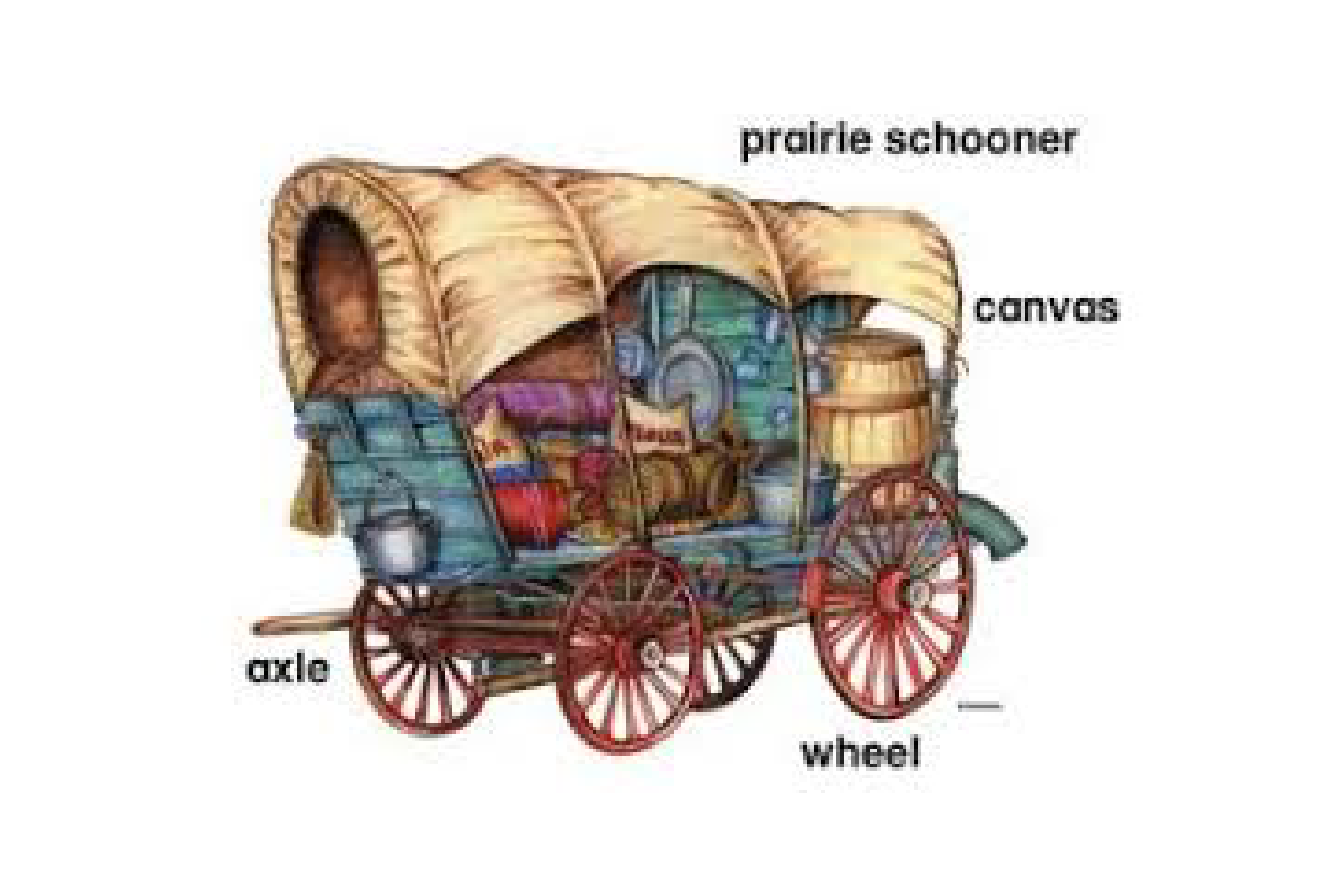

The wagons eleven-feet long, four-feet wide and two-feet deep. With only one set of springs under the driver’s seat and none on the axles the ride was so bumpy nearly everyone chose to walk. The covers were made of canvas, or a waterproofed sheeting called osnaburg. Frames of hickory bows supported the cloth tops, which protected pioneers from rain and sun. The rear wheels were five or six feet in diameter, but the front wheels were four feet or less so that they would not jam against the wagon body on sharp turns. Metal parts were kept to a minimum because of the weight, but the tires were made of iron to hold the wheels together and to protect the wooden rims. The rims and spokes would still sometimes crack and split, of course, and in the dry air of the Great Plains, they were also likely to shrink, which eventually caused the iron tires to slip off.

These early American mobile homes were called “prairie schooners” because they resembled a fleet of ships sailing across a sea of grass. In fact, when rivers were too deep to be forded and there was no timber to build rafts, the travelers would remove the wheels and float the wagons across.

Prosperous families usually took two or more wagons because the typical wagon did not have a large carrying capacity. After flour sacks, food, furniture, clothes, and farm equipment were piled on, not much space remained.

Marriages and births were always special occasions, and there were a surprising number of both on the Oregon Trail. Weddings were common either at the jumping off spots or, for those romances that bloomed along the Trail, on the Platte River or at Fort Laramie. A tongue-in-cheek conspiracy against the privacy of newlyweds by older-weds was called a “shivaree.” Virtually every train had expectant mothers, and their newborns were often named for natural features, events, or important days. There is one story of an orphaned baby who was passed from breast to breast to be fed.

They often killed buffalo and antelope, but a more dependable supply of meat was the herd of cattle following behind the wagons.

Highly infectious diseases, tuberculosis, measles, dysentery, flu, diphtheria, typhoid fever, smallpox and the scariest, cholera, whose symptoms include severe dehydration that could kill within a day—was caused by a water-borne bacteria that spread through the rivers, ponds, and streams that the Oregon Trail travelers used as both their water supply and public toilet. The most common treatment was opium, which reduced pain from cramping but didn’t cure the disease.

Estimates that about four percent of the settlers that traveled along the Oregon Trail died along the way, and that nine out of 10 of these deaths were caused by disease. With little time and few resources, wagon parties usually wrapped their deceased in blankets and left them in unmarked graves along the side of the trail.

Most people died of diseases, or in accidents caused by inexperience, exhaustion, and carelessness. It was not uncommon for people to be crushed beneath wagon wheels or accidentally shot to death, and many drowned during perilous river crossings.

Travelers often left warning messages to those journeying behind them if there was an outbreak of disease, bad water, or hostile American Indian tribes nearby. As more and more settlers headed west, the Oregon Trail became a well-beaten path and an abandoned junkyard of surrendered possessions. It also became a graveyard for tens of thousands of pioneer men, women and children and countless livestock.

Pioneers only packed what they needed:

- flour

- sugar

- bacon

- coffee

- salt

- rifles and ammunition