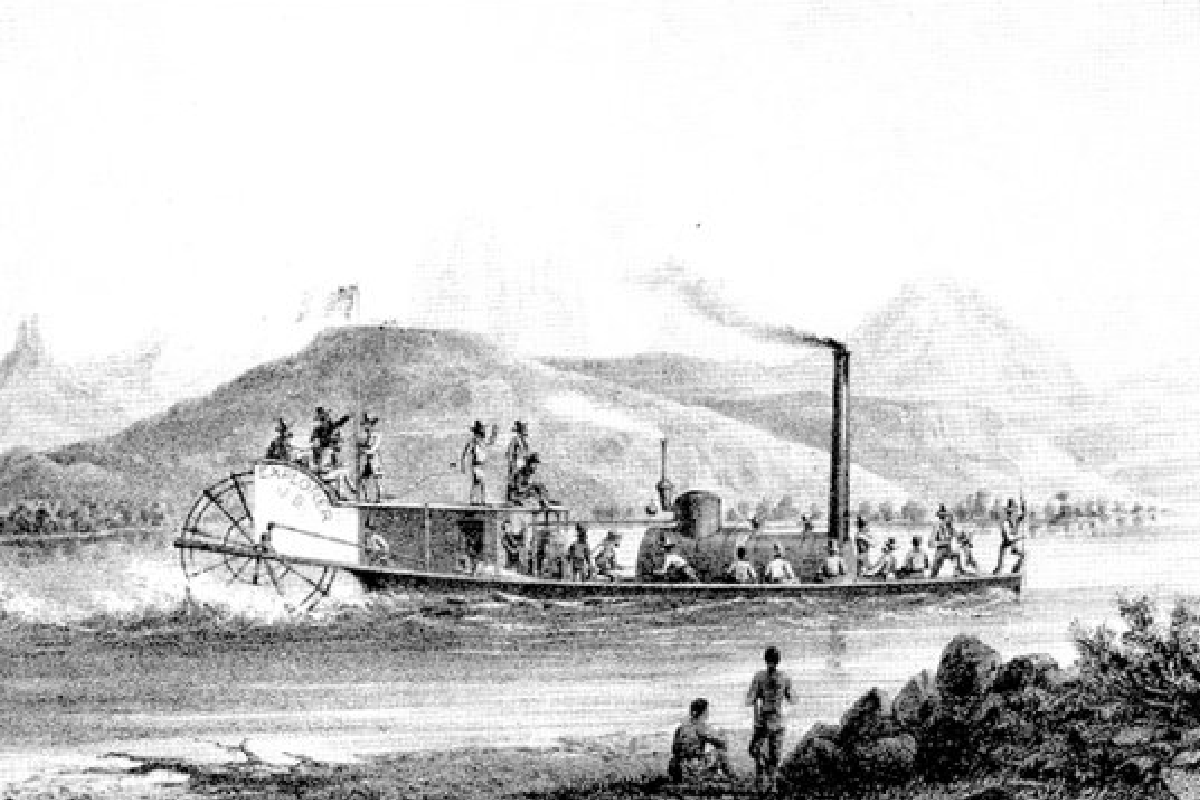

Little was known about the navigability of the Colorado River above Fort Yuma until 1858 when Captain George Johnson took his steamboat, a side-wheeler dubbed the General Jessup upstream from Fort Yuma. On his heels was, Lieutenant Joseph Christmas of the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers and his iron-hulled, 54-foot-long military stern-wheeler, aptly named the Explorer. They both set out to see how far up the river a ship could travel. The little Explorer certainly wasn’t the most graceful-looking steamer to navigate the river. The expedition artist, Baldwin Mollhausen called her a “water-borne wheelbarrow.” She had an oversized boiler and an undersized engine. The paddle wheel was at the stern and the boiler and smokestack shared the front with a four-pound deck-mounted gun. In between was a small cabin and observation deck. Atop the cabin, a U.S. flag flapped in the breeze.

Earlier, Johnson had offered to do the job for the Army for $3,000 a month, a fraction of the $75,000 the Army appropriated to do the same survey. His generous offer was refused and the Army went on a spending binge. It was assembled in Philadelphia, tested on the Delaware River, where it received poor grades, disassembled and shipped to San Francisco via Panama. Then it was transported by schooner to the mouth of the Colorado where it was reassembled in chilly, gale-force winds and christened, the “Explorer.”

The journey up the river to Fort Yuma took ten days and the little steamer managed to hit most of the snags and sandbars on that stretch of the river.

Earlier, Captain Johnson had decided to explore with his own steamboat, the General Jessup. Accompanying him on the journey was a curious assortment of fellows including the great scout, Paulino Weaver, Pasqual, the 6’7” tall, chief of the Yuma (“Quechan”) Indians, an Army officer and 15 enlisted men.

He took his side-wheeler up the silt-laden river to Pyramid Canyon, over 300 miles above Fort Yuma and determined the river was navigable all the way to the Virgin River. Then, he turned around and headed downstream.

The next day, near today’s Needles, they met Lieutenant Ned Beale and his Camel Corps surveying the 35th Parallel, the future Route 66. The meeting of a steamboat and a pack of hump-backed camels in the Mohave Desert had to be one of the most unlikely events in the history of the American West.

Meanwhile, Lt. Ives and his little Explorer, clawed their way up the Colorado and came to the same conclusion as Captain Johnson.

On his way back Ives, decided to leave his boat, head east and explore the mighty Grand Canyon. With the help of some local native guides, he snaked his way into the canyon, thus becoming the first white man to accomplish the feat. His comments afterwards were most interesting. “It can be approached, only from the south and after entering it there is nothing to do but leave. Ours has been the first and will doubtless be the last party of whites to visit this profitless locality.”

It’s all in the eyes of the beholder.