Lost gold mines are among our greatest natural resources; they don’t pollute the sky with columns of acrid smoke, befoul streams, or scar delicate hillsides with unsightly tailings. They don’t cost the taxpayers a cent to maintain and equip; there are no asphalt parking lots, restrooms, or visitor centers to clutter up the natural landscape.

True Believers are sure they exist. Others believe they as real as a pot of gold at the rainbows end.

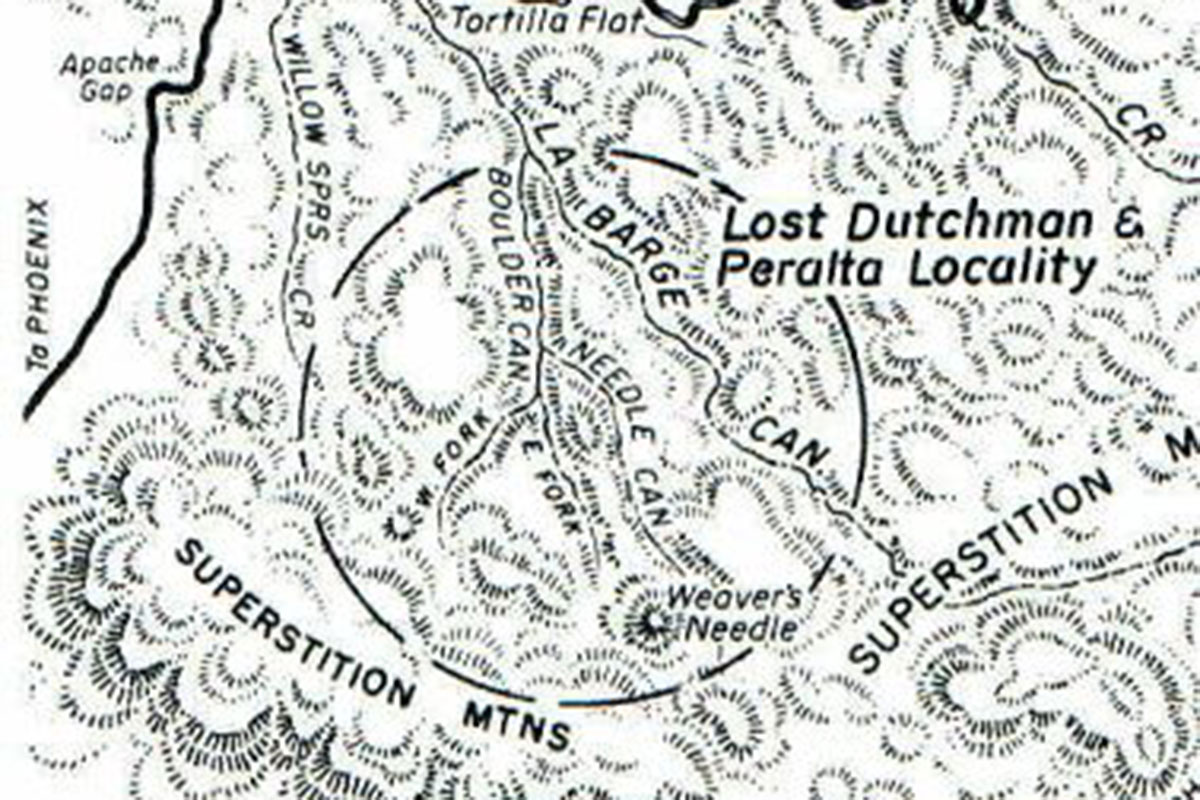

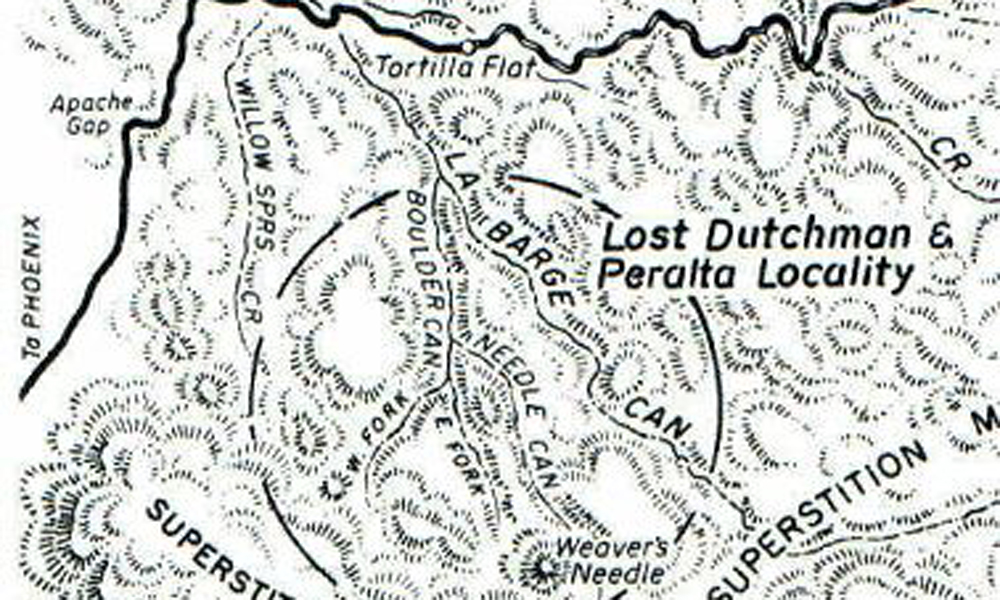

Of the hundreds of lost mines in the American West, the most famous of them all was the Lost Dutchman. The Lost Dutchman has it all, including embroidered narration’s, death bed ruminations, brooding, mysterious named mountains, ghost Apaches guarding its whereabouts and treasure beyond any Argonaut’s wildest dreams.

The mountains were named by the Pima Indians living along the Gila River. Apache raiders would plunder their villages then retreat to their lairs in the narrow, rugged canyons. When the Pima warriors would launch a punitive expedition against their ancient enemies, they would be lured into the mountains and never be seen again.

One legend says it began in the late 1845 when a party of Mexican miners were ambushed and massacred by Apache warriors as they were transporting gold from their mine deep in the Superstition Mountains.

Only one man, Don Miguel Peralta survived the massacre and he vowed never to return to the Superstitions. Then one night two men came to his aid in a cantina fight in a Mexican village and he decided to befriend them and share his secret. The two were German prospectors, named Jacob Waltz and Jacob Weiser. Don Miguel gave them directions to the old mine in the Superstitions and the two set out to find their fortunes.

At first they worked the mines without any problems but they became increasingly aware they were being watched by the Apache. One day Waltz went into Mesa for supplies and when he returned found Weiser had been killed by the Apache.

Another version of this story has Waltz killing Weiser so he could have all the gold to himself. Somewhere along the way Waltz seems to have morphed into a sinister, steely-eyed killer who ambushed anyone who dared follow him to his secret mine. In reality old Jacob was incapable of the violent nature attributed him by yarnspinners.

According to legend, Waltz left the mountains but returned periodically when he needed to replenish his supply of gold. Some tried to follow the old Dutchman and learn where his horde of gold was located but he always managed to elude them.

Later in life Waltz fell upon hard times and was living in south Phoenix in 1891 and was being cared for by a good-hearted neighbor, an African-American woman named Julia Thomas. During the heavy winter rains in February 1891 the Salt ran its banks and flooded the neighborhood. Waltz waited out the flood in a tree but due to the exposure he contracted pneumonia. He died soon after but on his deathbed supposedly told her the location of his gold mine. Ms. Thomas, along with a couple of brothers, Reiney and Hermann Petrasch headed for the Superstitions where they searched but were never able to find the treasure. Ironically, the trio would have crossed the very ground where, a month later prospector’s would discover rich gold deposits at the Black Queen and at the following spring Mammoth Mine where, over the next four years, they took out three million dollars in gold.

Claiming to have directions to Waltz’s mine, Ms. Thomas did manage to make a few bucks by selling maps on the streets of Phoenix for seven dollars each or whatever the traffic would bear.

Down through the years literally thousands of treasure seekers have searched for the Lost Dutchman but thus far, the brooding mountains have kept their secret.

Shortly after Julia and the Petrasch brothers returned from their futile search for the Dutchman’s gold in the fall of September, 1892 they shared their stories with a writer who had a fertile imagination and a penchant for lost mines named Pierpont C. Bicknell. This was the golden age of prevarication and he was a master. Bicknell took their story and with a grand display of embellishment and literary license, created the legend that most are familiar with today. It provided provocative clues to the whereabouts of the Dutchman’s gold and for the first time used the term “Dutchman’s Lost Gold,” incorporating the Weaver’s Needle. He also included the embroidered story of the fictitious Miguel Peralta. The story was published on the pages of the San Francisco Chronicle in January, 1895. Prior to the story the Dutchman’s Lost Mine, Weaver’s Needle and Jacob Waltz had not been linked together and Peralta family had not existed.

Another twist in the story has an Army doctor, named Abraham Thorne, who had attended to the sick Yavapai-Apache at Fort McDowell was befriended by a band who decided to reward his kindness by sharing some of their gold. He was blindfolded and led some twenty-six miles to a secret site at the bottom of a steep canyon. He was allowed to pick up all the gold nuggets he could carry. He later cashed them in for $6,000. He tried to return later for more gold but couldn’t locate it. Around that same time, 1871, two soldiers lost their way and stumbled into the gold field. They tried to return but couldn’t find I again. These are typical lost mine stories.

The story of the Lost Dutchman Mine might have become just another obscure legend had it not been for an easterner named Dr. Adolph Ruth, an amateur treasure-seeker who ambled into the Superstitions in the summer of 1931. Ruth had in his possession what he claimed was a map giving the location of the Peralta’s Las Minas Sombreras.

Crippled and elderly, Ruth was warned about the dangers of those mountains in the summer but he ventured in alone. When he failed to return a search party went looking for him but found no trace. Several months later his skeleton was found. The skull appeared to have a bullet hole and the mystery surrounding his death drew national attention. The map was missing and the True Believers insisted he was murdered for the map. A whole new generation of Dutchman hunters was born.

About that same time a group of folklore-loving Arizonans founded the “Dons of Arizona” to promote and preserve the colorful folklore the state, especially the Lost Dutchman Mine.

On April 16th, 1932 Tom Wiggins found a vein 4” by 6” thick of gold assayed at $12,000 to the ton about six miles from Superior in the far east side of the mountain range They said some nuggets were as big as marbles. It caused a stampede of prospectors but it soon played out.

During the late 1945, John T. Clymenson aka Barry Storm took Pierpont Bicknell tales to the next level embellishing every legend from the Jesuit’s and Peralta’s to the Dutchman and Weaver’s Needle and publishing Thunder God’s Gold that in 1948 was made into a movie, Lust for Gold that starred a young Glenn Ford as old Jacob. The beautiful Ida Lupino was written in to provide some romance.

Barry Storm’s book did more than anything yet to perpetuate the mythical Lost Dutchman Mine.

Between 1959 and 1991 a full-scale feud broke out at Weaver’s Needle between Ed Piper and Celeste Marie Jones. Both were seeking the mythical Lost Jesuit treasure and it created a contentious situation between the two camps. Ms. Jones an African-American lady reputed to be a former opera singer, carried a sawed-off .30-06 rifle and a pistol strapped to her hip. Piper went similarly armed. She believed the gold was inside Weaver’s Needle and planned to drill a shaft down through the core then blow it up.

Neither seemed to be the violent sort but both attracted an assortment of supporters who claimed to be bodyguards. A saloon in Apache Junction hung a recruiting post for each complete with sign-up sheets. The frivolity ended when a fight broke out among the resulting in three dead.

The feud ended when Piper died of natural causes in 1962 while Ms. Jones abandoned her claim and took off for parts unknown.

Congress designated it a Wilderness Area in 1964.

As I’ve said many times before, the real treasure in the Superstitions is the natural beauty of the twisted, steep-sided canyons, buttes, mesas and spires. Wild, untamed and unforgiving. For those adventuresome souls who dare venture in there you have to do it on her terms. Best time to visit is in the spring when the wild flowers present a variegated profusion of brilliant colors. Worst time is the summer.

A few years ago a “Dutchman hunter” tried it in the month of June. He had to be saved by Search and Rescue. He tried the same thing a year later and they recovered what was left of his body six months later.