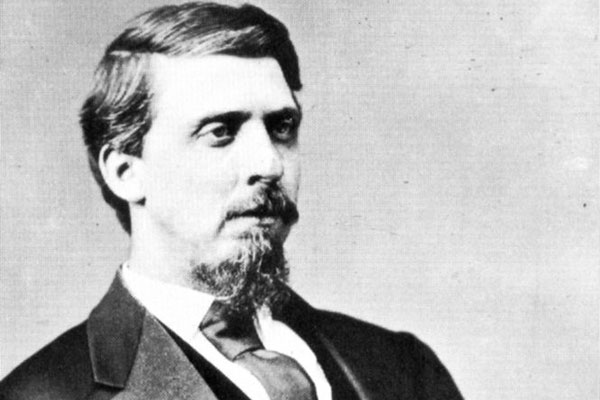

On May 10, 1875, a new judge came to the bench in Fort Smith, Arkansas. His territory covered about 74,000 square miles in parts of Arkansas and the Indian Territories (now eastern Oklahoma). The Western District of Arkansas was both a circuit and district court—meaning the verdicts could not be appealed (except to the president of the United States).

On May 10, 1875, a new judge came to the bench in Fort Smith, Arkansas. His territory covered about 74,000 square miles in parts of Arkansas and the Indian Territories (now eastern Oklahoma). The Western District of Arkansas was both a circuit and district court—meaning the verdicts could not be appealed (except to the president of the United States).

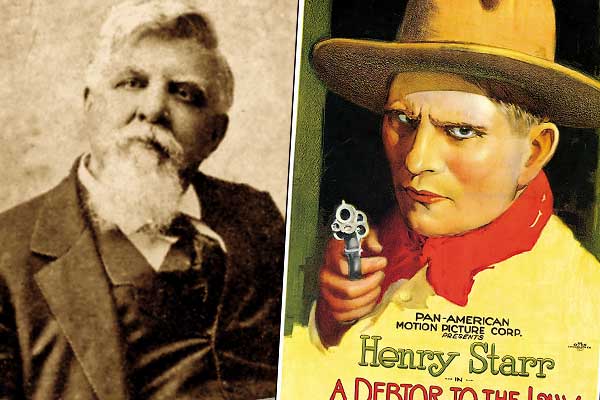

Isaac C. Parker had become, arguably, the most powerful judge in the country. He held dominion over life and death—which inspired his “Hanging Judge” nickname.

For 14 years, he wielded that power with diligence, a sense of duty and, yes, maybe a touch of arrogance. But his power did not last. A fair number of folks in Washington, D.C. were concerned that convicted criminals in the Western District—especially those sentenced to death—had no appeal.

Parker was also his own worst enemy. He had ticked off a lot of folks in his life, especially political opponents. The judge had a thin skin; anybody even mildly critical of him became, in Parker’s eyes, an enemy of justice and a friend of crime.

In 1883, some parts of his jurisdiction were given to courts in Texas and Kansas, at least in part to reduce Parker’s case load (unsuccessfully). Six years later, Congress eliminated the circuit court function at Fort Smith, meaning that convictions could be appealed.

Once the law went into effect on May 1, 1889, others could legally question and change Parker’s rulings, which did not sit well with the judge—especially considering what came to pass.

Between 1891 and 1897, the Supreme Court overturned over two-thirds of the Western District convictions. Forty-four of the death penalty cases came up for appeal—some of them two or three times. Thirty of them were overturned, often for errors on the part of Parker.

Frequently, the error was found in his instructions to the jury. Parker made no bones about what verdict he expected (usually “guilty”)—and the jury almost always went along with him.

Plus, Parker believed in “duty to retreat,” which argued that persons threatened with physical harm had to take every opportunity to get out of the situation before, ultimately, taking violent action to defend themselves. That wasn’t what most courts believed; a mere verbal threat could be legal justification for deadly response. The Supreme Court overturned several Parker cases on that basis.

Parker responded by attacking the high court with tough language, accusing the justices of knifing the “trial judge in the back” and allowing the “criminal to go free.” He claimed the reversals had filled the Fort Smith jail to overflowing and “contributed to the number of murders in the Indian Territory.”

In 1895, Congress stripped the Western District of its jurisdiction over the remaining Indian Territories. That went into effect in September 1896. By then, Parker’s health was failing. He went before the Great Judge 11 weeks later.

But the beginning of his end came 125 years ago, when Congress took away some of the rope from the Hanging Judge.