Even though the dollar is not what it used to be, a few bargains can still be had.

Even though the dollar is not what it used to be, a few bargains can still be had.

For example, a paltry $16 million will purchase a breathtaking spread—nearly 25,000 acres—found less than an hour northeast of Cheyenne, Wyoming. The realtor assures me it’s still on the market, and the property contains everything one might require to operate a very sizable working ranch: pasture, water, 10 homes, a “classic old” barn, lodge, bunkhouse, cookhouse and a recreation area. That’s for starters.

What the prospectus doesn’t list is the remarkable history of the Y-6 Ranch, the family who lived there and the man who built it, Charles Burton Irwin. C.B. Irwin’s story is a story of the West—of trains and the men who robbed them, of rodeos, Indians and a trio of prize-winning cowgirls who grew up there. You got horseracing and horse trading and hustling.

The history of the property is one of high aspirations, showmanship and tragedy. Like Shirley Morris, a filmmaker who’s planning a documentary on the Irwin family, says, “Every letter, every turned page, is another whole movie.”

“The story about the Irwins is the biggest story to come down the pike since How the West Was Won,” says Morris, whose most recent project was Oh, You Cowgirl! A True Story About America’s Unsung Heroes (find it at TheCowgirlMovie.com). In part, the film tells the enigmatic story of the girls who all acted the role of one of America’s most beloved rodeo stars, Prairie Rose. C.B. Irwin played a major role in that bit of show business as well.

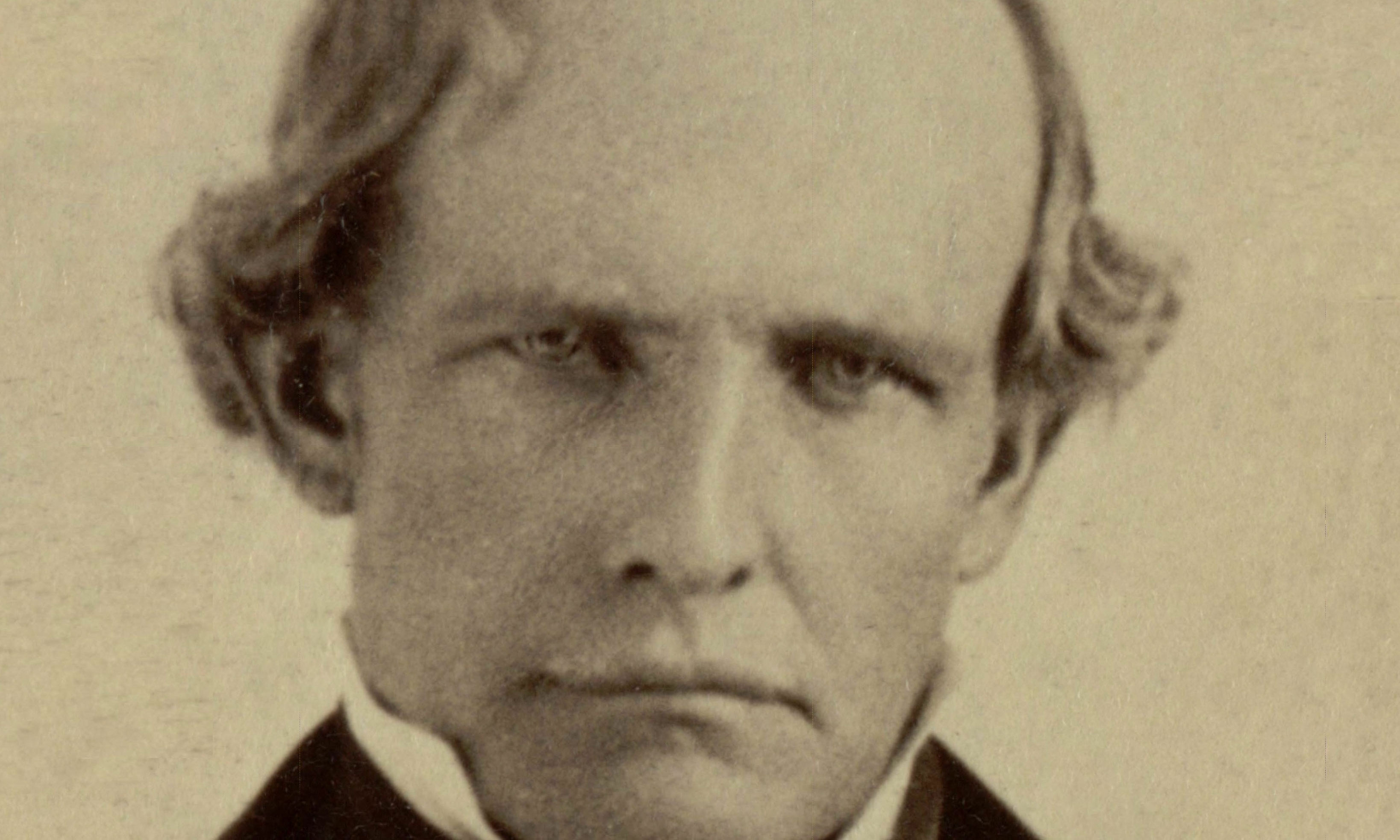

The story of Irwin, who weighed over 500 pounds when he died in a car accident (a tire blew because of his weight), is either one of legendary achievement or colossal chicanery. Actually, where Irwin is concerned, the two are indistinguishable.

“C.B. (as most people called Irwin, except Will Rogers, who called him Charley) was born on August 14, 1875, and weighed 14 pounds. He was the son of a Missouri blacksmith and was a blacksmith as well,” Morris tells us.

“Irwin and his wife, Etta, left Missouri for Colorado, where they did well until a fire wiped them out. They pulled up stakes and headed north to Wyoming.

“C.B. had a dream—he was determined to be a land baron, and it was because he was C.B. Irwin that he was able to make it all happen. He was not going to accept anything less.

“He started working for the L-5 Ranch as a hand, saving his money and negotiating smaller parcels of land. He went to work for Sen. Francis Warren on his spread, and it was during that time that he met Gen. Pershing (who married Warren’s daughter). They all became very, very close friends. Years later C.B. and his daughter Joella would supply Pershing and the Army all of the horses for WWI.” (For an in-depth look at Irwin’s horseracing activities, and considerably more, see Laura Hillenbrand’s acclaimed novel Seabiscuit: An American Legend.)

The fascinating thing about C.B. is how he managed to be everywhere and do everything. He and his brother Frank sang for their friend Tom Horn, just before the trap opened and he was hanged in 1903 for murder on the newfangled, automated Julian Gallows.

As a detective for the Union Pacific, C.B. chased and caught Bill Carlisle, one of the last of the great train robbers. The detective did so twice, actually, in 1916 and in 1919.

Irwin’s horse Steamboat was a featured attraction in bucking bronco contests from 1901-14, and it’s Steamboat who is seen on the Wyoming state license plate.

And Irwin started the Irwin Bros. Wild West show, which lasted from 1913-17 and is regarded as one of the best. He also created a motion picture company, which seems to have produced only two movies. One of them, Fall Round-Up on the Y-6 Ranch, is supposedly based on Tom Horn and was partly filmed at the Colorado State Prison.

“C.B. and his wife, Etta, had three daughters and a son, but they ended up adopting and fostering 17 children,” Morris says. “It had a whole lot to do with the Orphan Trains. At that time there was an Orphan Train that went through the states, like puppy mills. What I’m thinking is that C.B. was like all of the ranchers and farmers in the area—if they didn’t have a boy to help, you’d bring in kids and adopt them.”

But what fascinates Morris, and what’s motivated her to pursue the Irwin story, is how Irwin encouraged his three daughters to become not just champion riders but also overachievers in every area of their lives.

“This family really should have a very special place in Western history, because it was not just one member of the family that was outstanding, it was the entire family. They each had something to contribute to the West.”

Irwin’s son, Floyd, was well on his way to becoming a great cowboy—he had won the Pony Express race in Pendleton, Oregon—when he died in a freak accident. “Floyd ran away,” Morris says, ”and became a ringmaster for the circus. He got married and told C.B., ‘I don’t want to do the rodeo anymore.’ C.B. talked him into coming back and helping out for just one more show.

“So Floyd agreed to do Cheyenne Frontier Days for the final time. But they were bringing in some cattle, and one was not cooperating. He threw his lasso. It missed, he thought, and as he turned his horse to leave, the rope snapped, the horse reared and the horse’s head hit Floyd and crushed his skull.”

As bizarre a death as that was, something similar happened to one of C.B.’s adopted sons as well. “The kid who C.B. took under his wing after Floyd died, he was grooming this boy to take over a lot of the duties on the ranch,” Morris says. “It wasn’t more than a few years later that this kid was killed in an almost identical manner. He was out there roping steer, the horse slipped and landed on him, and broke his neck.”

C.B.’s girls, however, were all renowned for their horsemanship. Each of his daughters won events and acclaim in the rodeo world.

“C.B. expected his children to be as accomplished as he was. He wouldn’t accept anything less,” Morris says. “The very first cowgirl to come out of the greater Irwin family was Margaret, C.B.’s sister-in-law, who won the first Denver Post Cup for the relay race, and she won it three or four years in a row. She has been nominated to the Hall of Fame in Cheyenne as an outstanding cowgirl of her time.

“Teddy Roosevelt said that Joella was the finest horsewoman he had ever met. He was just amazed at her abilities. She also won the Denver Post Cup and won countless relay races. Later Joella became a fine artist, and the Los Angeles County Museum featured her in her own show, in 1951.

“And his daughters, at a time when women didn’t even have the vote [nationally], they became champions in their own right. Not only were they champion cowgirls, they went on to be champions in other things. Frances went on to be the very first woman horse trainer in America. She worked with Tom Scott and had a string of wins that would rival anyone’s today. She was inducted a few years ago at Longacres [racetrack]; she knew horseflesh like her father knew horseflesh.

“You can’t be a champion at everything, and one of the things that C.B. was not as good at was watching his pocketbook,” Morris admits. “He ended up broke many times. But he was a man of the West, and he was always out for the challenge. He would always step off that one ledge if there was a challenge, or competition or something he wanted. He was good for the risk.”