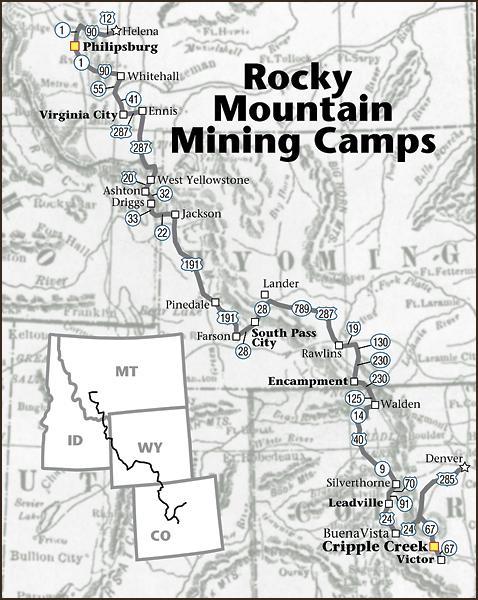

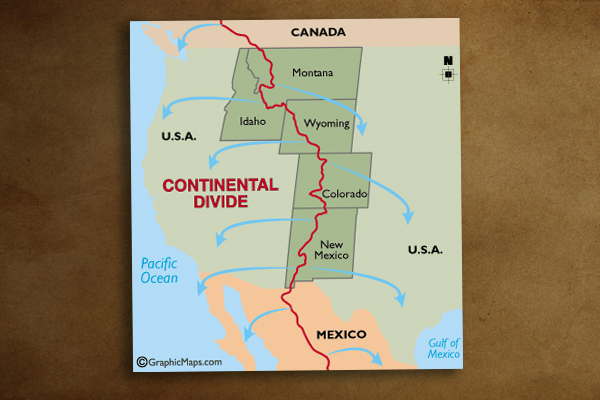

The backbone of the continent—the Continental Divide—is rocky and rugged in places, and geologically diverse.

This landscape from Colorado to Montana is high country known for scenic vistas and diverse mineral resources. Beginning in the 19th century and continuing to the present, miners have harvested the bounty of nature: gold, silver, copper and sapphires are some of the riches they’ve taken home.

The mother lodes they found spawned fast-growing towns and rich histories, and today you can explore the places and learn the stories of their booms, their busts and their people.

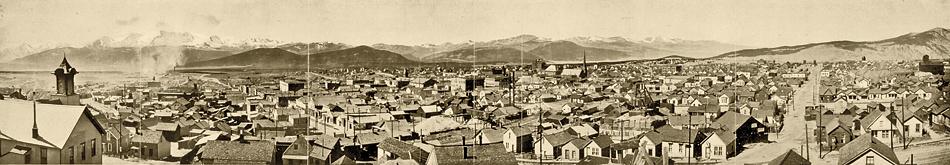

Miners pulled more than $18 million in gold from the nearly 500 mines in the Cripple Creek district high in the Rocky Mountains just to the north of Pikes Peak in the late 19th Century. Bob Womack—some called him “Crazy Bob”—filed on the El Paso lodge mining claim on October 20, 1890. When his ore assayed at $250 in gold per ton, the rush was underway.

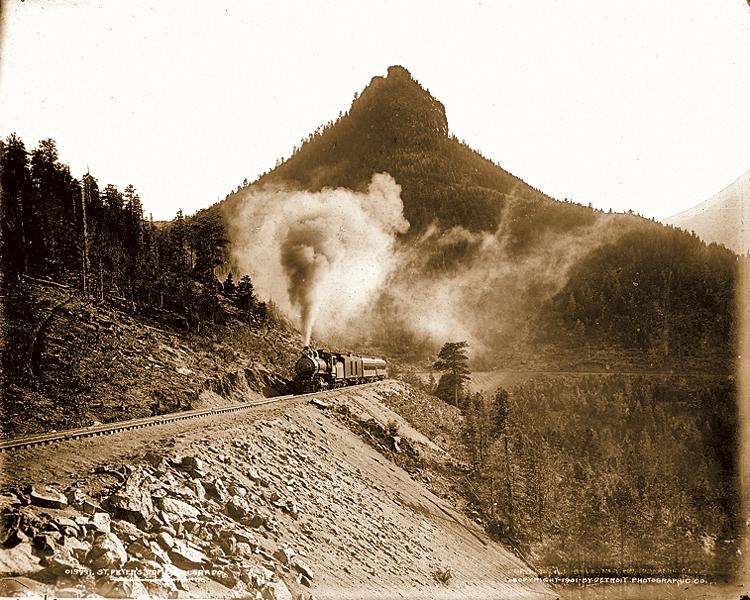

During the heyday, three railroads and two electric trolley systems served the gold camp. The “Gold Belt Line” narrow-gauge Florence and Cripple Creek Railroad linked the gold camp with Florence, Colorado, by climbing through Phantom Canyon. You can drive the route of this old railroad by taking the Phantom Canyon Road, but be forewarned, it is steep, narrow and not for anyone who dislikes heights, one-lane roads with two-way traffic or blind corners. For adventurers, however, it is an awesome drive.

Gold mining continues in the region by the Cripple Creek and Victor Gold Mining Company. The Cripple Creek Heritage Center has mining history displays, and opportunities for a guided tour of a modern working mine, as well as a visit to the historic Mollie Kathleen Mine. Nearby Victor also has a rich mining heritage. Learn more at the Victor Lowell Thomas Museum. Gold Rush Days are held in mid-July with mining games, gold panning, a parade and other activities.

From Cripple Creek and Victor head north through Buena Vista to Leadville, location of one of the richest historic silver districts in the country, and home of the National Mining Hall of Fame and Museum, a showcase of American mining. Outstanding examples of ores and precious rocks and minerals are on display along with artifacts, historic photographs and exhibits including a replica underground hard rock mine and a prospector’s cave. The museum also has a collection of mining tools such as hammers and drills that show how mining technology changed through the years.

As you travel north from Leadville through Silverthorne and Walden, you are on a route speculators and miners took when they fled Cripple Creek to the next big strike: the discovery of copper in what became the Grand Encampment Mining District.

Grand Encampment Mining District

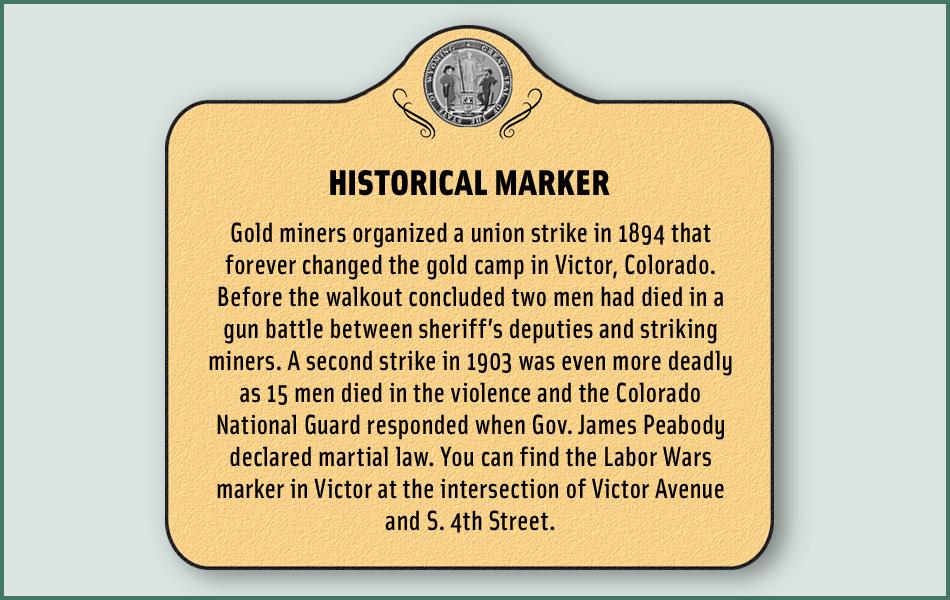

Edward Haggarty herded sheep but his primary interest in the Sierra Madre mountain range was the search for minerals, and on a spring day in 1896 he found the mother lode—a copper deposit that would be developed as the Rudefeha Mine (named for the men who backed his mining work—Rumsey, Deal, Ferris and Haggarty). In May 1897, the word was out and men who had rushed north from Cripple Creek staked the Wyoming town of Grand Encampment at the foot of the mountains. Miners and boomers came quickly, many of them like Milt Englehart and Edward Parkison from Cripple Creek, Colorado. They opened stores to serve the mining industry and brought newspaperman Grant Jones up from Cripple Creek as well. He would take over the promotion of the area, quickly getting articles placed in newspapers from Philadelphia to Denver.

Jones would ultimately open his own paper, the Dillon Doublejack, published in the town that grew closest to the mine. In addition to the Rudefeha Mine (which later became the Ferris-Haggarty), other copper mines were quickly developed and spawned such Wyoming towns as Battle, Copperton, Elwood and Rambler.

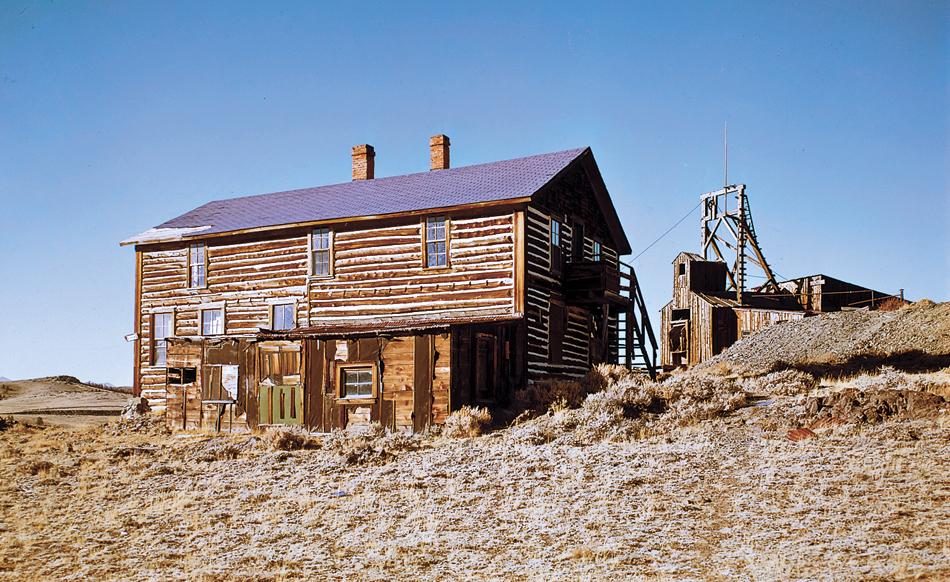

From 1897 until 1908 Grand Encampment was the hub of the copper district. Stagecoach service provided a link to the Union Pacific Railroad at Walcott Junction, 40 miles to the north. Freighters like Gee String Jack Fulkerson hauled goods to the mines and mining camps, and returned to the North American Copper Company smelter with loads of copper ore. But that transportation was difficult—both costly and dangerous. So the company hired the Riblet Tramway Company from the Pacific Northwest to build a 16-mile-long aerial tramway that could transport the ore from the Ferris-Haggarty to the smelter that had been constructed along the Grand Encampment River near the town. This engineering marvel was the longest aerial tramway in the world at the time. It operated from June 1903 until August 1908 when the last of three fires rendered the smelter inoberable.

The copper boom went bust shortly thereafter, but the Grand Encampment Museum has one of the original tramway towers, plus three replica towers that have original cable and ore buckets. Also on the grounds at the museum are original buildings from the town of Battle, homestead and stagecoach cabins, a one-room school and a two-story outhouse.

South Pass City – Birthplace of Woman Suffrage in the West

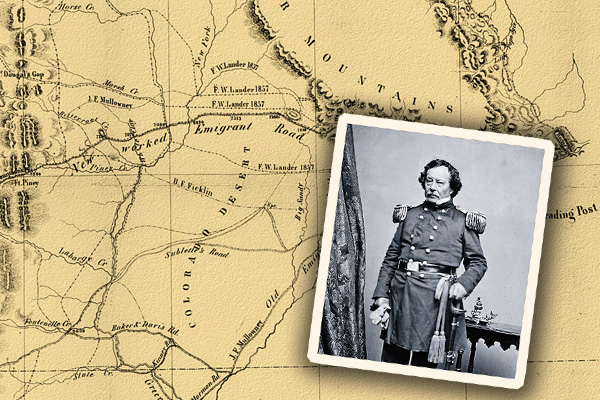

An even earlier mining boom occurred farther north in Wyoming in 1868 with the discovery of gold and the beginning of South Pass City, which is now a Wyoming State Historic Site located in central Wyoming just below the famous pass that hundreds of thousands of overland emigrants crossed. The remnants of the town line the single street, which is one of the best-preserved 19th century mining towns in the West.

Buildings that served the miners are restored, as is the Carissa gold mine, which was the primary operation in the South Pass District. Although the gold rush lasted just a short time, the Carissa was operated well into the 20th century when underground mining took place. A new millhouse constructed in 1929 and upgrades after WWII kept the mine in operation on a periodic basis until it closed permanently in 1954.

With the restoration work at the Carissa, it is now open again for tours (Thursday to Sunday during the summer). The 1.6 mile Flood & Hindle Mining Trail that follows Willow Creek from South Pass City has been developed with interpretive signs, and replica equipment from the mining era when mills were used to crush the gold-bearing ore. Other operations included sawmills where workers shaped mine timbers.

South Pass City is known too, for the role its citizens played in bringing equal suffrage. Esther Hobart Morris lived in the mining town and urged territorial lawmakers to sponsor the legislation that gave Wyoming women the right to vote—the first territory in the nation to approve such an act. Morris became the first female justice of the peace in the United States in 1870, taking over the position after James Stillman resigned in protest of the law that gave women the right to vote!

Montana’s Mining Roots

The issue of equality for women will be presented by the historian re-enactors at Nevada City, Montana, in August, one of many summer events that bring history to life in the historic site located in southwest Montana. While the buildings of Nevada City have been brought in from all over Montana, the original structures in use down the road a mile in Virginia City are in their original location. These two mining towns take you back to the days of the gold rush in Alder Gulch, one of the earliest booms in what became Montana Territory.

Born during the Civil War, this was a town divided with Unionists and Southern sympathizers each supporting their side in the war. Set aside all differences when you attend the Virginia City Grand Victorian Balls, where women in 1860s style gowns and their dashing male escorts take to the dance floor as they swirl through the steps of the old dances. If you want to participate, you’ll need appropriate duds (they are available at Rank’s Mercantile in Virginia City), and you can take a dance lesson the afternoon of the ball. Then participate in the grand promenade through town before you dance throughout the evening and share a midnight supper.

Montana is dotted with the ghost towns of the gold mining era, from Bannack, the first territorial capital, which is now a Montana State Park (there was damage to many of the historic structures in Bannack in the summer of 2013 due to a rain and hail storm) to Granite, an 1890s silver boomtown that is now Granite Ghost Town State Park.

The first silver deposits were uncovered in the Granite area in 1865 with the Granite mine developed in 1872. It led to a bustling community that included a hospital, church, many homes and businesses, and the Miner’s Union Hall. The boom that caused Granite to grow went bust in the silver panic of 1893. Although mining would resume the town of Granite never again reached its peak population of 3,000 miners, and ultimately was completely abandoned. If you visit, you can still see remnants of this once vibrant town.

Today you can do some mining of your own not far from Granite Ghost Town in Philipsburg, called P-Burg by the locals. The gemstone you’ll find here, most

likely, is a Montana sapphire and you can seek your own at the Gem Mountain Sapphire Mine, or do your “mining” in the comfort of the Gem Mountain Sapphire Gallery in Philipsburg (you buy a bag of dirt and then sift and wash it to uncover the gem-quality sapphires).

Some folks come and sit most of a day walking away with several stones. I was there just long enough to “mine” a single bag of dirt that resulted in six small sapphires that I later had heat treated so I can make them into pieces of jewelry. If all that “mining” makes you hungry, step into The Sweet Shop for a piece of homemade saltwater taffy. In the evening take in the Vaudeville Variety Show in the Opera House Theater, for a return to the heyday lifestyle of the old mining camps.

Candy Moulton, the author of Roadside History of Colorado and Roadside History of Wyoming, has danced at the Virginia City Victorian Ball, been deep in the Oceola Tunnel of the Ferris-Haggarty Mine and panned for gold at South Pass City.

Photo Gallery

– by William Henry Jackson/ Courtesy Library of Congress –

– by William Henry Jackson/ Courtesy Library of Congress –

– by J.E. Stimson/Wyoming Division of State Parks and Cultural Resources –

– by Candy Moulton –

– by Jack E. Boucher/ Courtesy Library of Congress –

– by Candy Moulton –