Just the sound of her name draws a mental picture: Mattie Silks.

Just the sound of her name draws a mental picture: Mattie Silks.

No plain, dowdy woman in a calico dress would ever wear such a name; no girl with prim schoolmarm glasses or neck-strangling high collars would answer to it.

But a “love merchant” in rich brocade and lace would; a woman whose custom-made gowns always had two pockets—one for her gold coins, the other for her ivory-handled pistol; a woman known as the undisputed “Queen of Denver’s Red Light District” would feel right at home in that name.

And she did, this woman who bragged she was never a prostitute—“the man doesn’t live who has enough money to buy me,” she supposedly said—but was one of the Old West’s most successful businesswomen in supplying “soiled doves.”

Her girls were known to possess “the prettiest of faces, the tiniest of waists, the creamiest of bosoms, the daintiest of giggles, the best of conversational skills, the most imaginative of techniques, the perkiest of personalities … and the best of acting abilities (leading the customer to believe that she really cared),” notes Clark Secrest in Hell’s Belles.

Mattie was born somewhere in the Midwest around 1846—some say Kansas, others Indiana—and there are only hints at her true name: Martha, it seems was probably her real first name, but one document has been found that seems to refer to her as “Mate Wineman,” but no one knows for sure. What is clear is that she never had any profession except running a “sporting house,” first making her name at age 19 in Springfield, Illinois, as the youngest madam on the frontier.

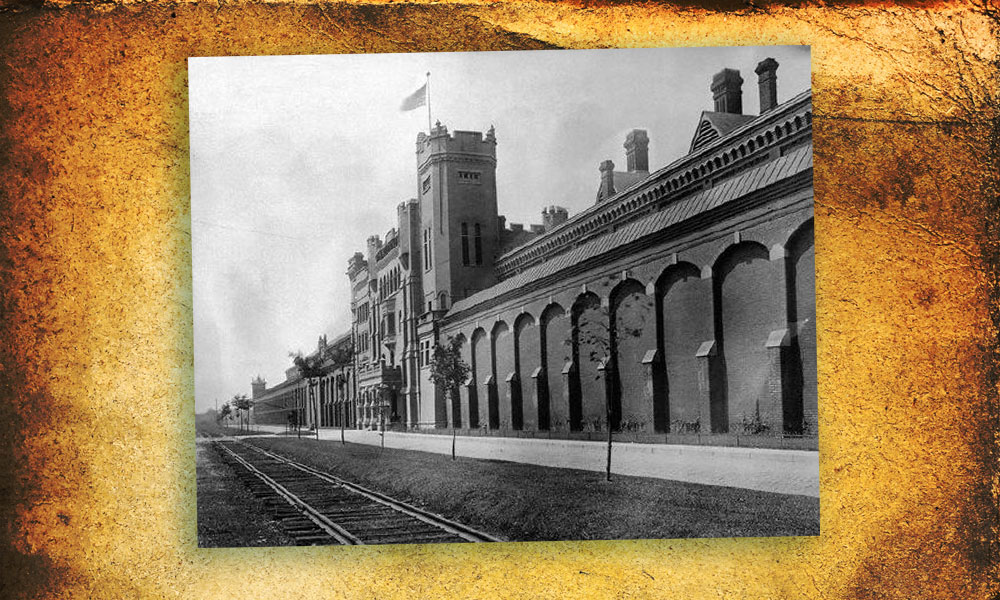

Seeing greener pastures farther West, Mattie eventually gathered up four girls and a tent, and set up a traveling bordello that worked the Colorado goldfields. About 1876, she settled in Denver and opened a fashionable house on Holladay Street (now called Market Street), known as “the wickedest thoroughfare in the West,” according to Anne Seagraves’ Soiled Doves: Prostitution in the Early West, the most popular book ever written on the subject. Seagraves reports that this one street boasted 1,000 ladies for sale in all kinds of establishments. At the top of the list were the elegant “parlor houses” like Mattie’s, while the bottom of the barrel were the shabby “cribs”—a dirty bed with a piece of oilcloth across the bedspread to protect it from the muddy boots of the customers.

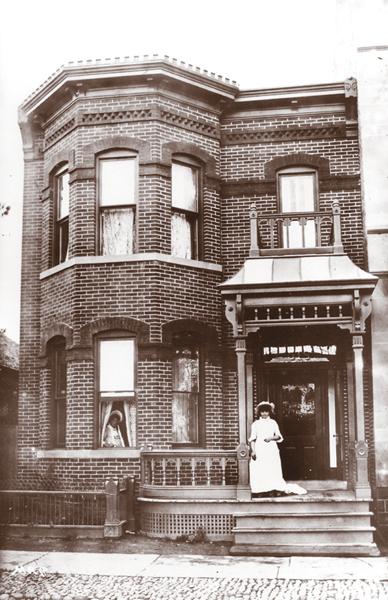

Mattie eventually bought the single most famous parlor house in town—House of Mirrors—built by Denver’s other legendary madam, Jennie Rogers. After Jennie died in 1909, Mattie moved into the house that seemed made for her.

“The House of Mirrors was the perfect setting for the dynamic Mattie,” Seagraves notes. “This opulent establishment had doorposts carved to represent phallic symbols, an elegant reception room and a parlor with plate glass mirrors that covered the walls. The chandelier, made of hundreds of glass-faceted prisms, hung from an 8-foot mirrored ceiling and gave the room a shimmering beauty that reflected upon a golden harp and rich brocade chairs.”

Life in the house was as good as it got for prostitutes. Mattie served two good meals a day: breakfast at 11:30 a.m. and dinner at 5 p.m., Secrest reports. The girls were required to dress nicely, and most were indebted to Mattie for their clothes. She allowed them to keep half their earnings, but from that they had to pay room and board. By all accounts, she treated her girls well and once bragged she never hired anyone who wasn’t experienced, emphasizing she never turned “innocent” girls into hookers.

Here’s how Secrest describes her: “Chubby and curly-locked, Mattie Silks was an enduring businessperson in an era when few women embarked upon any sort of business venture, enduring or not. She was successful in an enterprise that other women frowned upon outwardly but looked upon privately with some curiosity: Mattie Silks was a bordello madam—and a good one—famous throughout the West. Plus, she never apologized about it.”

She would boast that she made about $2 million in her career (and she spent it all).

Mattie’s major failing was her lousy taste in men. It’s said that her last name came from her first husband, Charley Silks, but when and where she married him, and when and where she disposed of him, has never been established. What is known is that her “true love” was a good-for-nothing gambler, drinker, rustler and general scoundrel named Cort Thomson, who she met in 1877 and married in 1884. Seagraves describes him as “a cocky little foot racer who wore pink tights and star-spangled blue running trunks and bragged ‘he was too proud to do a day’s work.’” Instead, he took thousands from the woman who adored him, even though he beat her, cheated on her and embarrassed her publicly.

To get him out of Denver—and supposedly out of harm’s way—Mattie bought a 1,400-acre ranch near Wray where she kept Cort and her 21 racing horses (which raced in Denver under the ownership of Mrs. C.D. Thomson, who no one in Wray knew was the famous Mattie Silks).

Cort had left a wife and child to run off with Mattie, and about 1886, a little girl came into their life that was either his daughter or granddaughter (historians aren’t sure). While he wanted nothing to do with the child, Mattie did, adopting the girl and sending her to a good boarding school. Eventually, the girl became one of Mattie’s beneficiaries.

Mattie almost came to her senses about Cort in 1891, when she sued him for divorce and charged him with being a “drunk, wife beater and philanderer,” but soon after, they reconciled! He died in 1900, either from spoiled oysters, or, as the Rocky Mountain News reported, from whiskey and opium. Mattie buried him in style.

She hired “Handsome” Jack Ready as her bouncer, a man many years her junior, but they became lovers and in 1923, when Mattie was in her mid-70s, they married.

Mattie died on January 7, 1929. She had a quiet funeral and was buried next to Cort. Handsome Jack died a couple years later, a pauper.

The great businesswoman who’d led such a lavish life left an estate of $4,000 in real estate—the cottage where she lived—and some $2,500 in jewelry, including the two diamond rings she always wore and her trademark: an 11-diamond cross that hung at her neck.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –