Deserted by her husband, a determined teenage mother is left to raise her young son in France’s colonial outpost, New Orleans. Not an auspicious beginning for what would become one of the most influential families on the American frontier.

Deserted by her husband, a determined teenage mother is left to raise her young son in France’s colonial outpost, New Orleans. Not an auspicious beginning for what would become one of the most influential families on the American frontier.

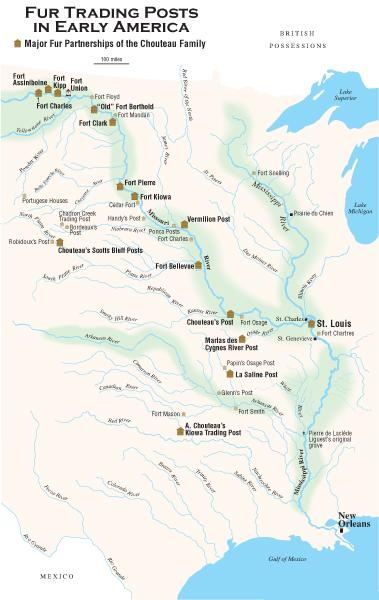

At the start of the 18th century, Europe demanded furs for its latest fashions as France, Spain and Great Britain vied with each other to dominate the North American fur trade. France claimed most of Canada and the Mississippi-Missouri River basin, which the French called Louisiana. They used the Mississippi and Missouri Rivers as highways, traveling inland to barter manufactured goods for deer and buffalo hides, beaver pelts and other furs from the Indian tribes. After the French founded the port of New Orleans near the mouth of the Mississippi in 1718, it soon became the administrative and economic center of Louisiana.

Into this stronghold sailed French emigrant René Chouteau, out to make his fortune. His first job at the port was as a tavern keeper. At 25, he married 15-year-old Marie Thérèse Bourgeois, a native of New Orleans who had lost her father when she was six. Two years later, in 1750, Marie Thérèse and René had a son named Auguste.

Family tradition recounts that René was abusive, and on one occasion, he cut Marie Thérèse’s face, leaving a scar. Several years after the birth of Auguste, René deserted his family and sailed back to France. Marie Thérèse must have said good riddance. With her husband gone and her father dead, she called herself the Widow Chouteau. Family records do not disclose how she provided for Auguste and herself.

Stimulating the fur trade

In 1755, a small group of French colonists led by Pierre de Laclède Liguest dis-embarked at the New Orleans port.

Laclède, 26, was ambitious and determined to make his fortune. He had been born into a middle-class family living near the French-Spanish border and graduated from the Académie d’Armes de Toulouse, where he won two swordsmanship contests. Not only did Laclède have a military education, but he was also knowledgeable about agriculture, milling and civil engineering, and he spoke several languages.

The French and Indian War, part of a larger, European war between France and Great Britain, had broken out the year before when a small band of Virginians led by a young George Washington unsuccessfully tried to expel the French from Fort Duquesne in present-day Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Laclède had been working on agricultural and business ventures in and around New Orleans when he volunteered to join the military staff of Col. Gilbert Antoine de Maxent, who also happened to be a well-off New Orleans businessman. The colonel liked young Laclède and took him under his wing.

No record relays how or when Laclède met Marie Thérèse, but they eventually fell in love. They wanted to live as husband and wife, but there was a problem: René Chouteau was still alive and well in France, and the Catholic Church and French Government did not recognize divorce. Seeing no other choice, Marie Thérèse and Laclède defied church and state, and began living together as husband and wife. Marie Thérèse had four children with Laclède—a son, Pierre, born in 1758, followed by three sisters. Since Marie Thérèse and Laclède were not legally married, they gave the children the surname Chouteau.

France’s trade with the Indian tribes declined due to the war. Wanting to stimulate the fur trade, the new governor of Louisiana, Jean Jacques D’Abbadie, gave Col. Maxent exclusive trading rights for six years on the west bank of the Mississippi River and along all of the Missouri River. Colonel Maxent and Laclède formed a partnership, with the colonel providing most of the capital for the venture and Laclède traveling upriver to develop contacts with the tribes and trade for furs and hides. To succeed, Laclède needed to establish a good relationship with the Osages.

The Osages were one of the most powerful tribes in North America, centering their home territory in what is now the state of Missouri. They had acquired firearms early on from Europeans and dominated even the fierce Comanches and Apaches. The good news for French traders was that the Osages considered the French their friends and desired French goods.

In 1763, Laclède headed up the Mississippi River with 13-year-old Auguste and a band of workers. After three months and 700 miles, they reached St. Genevieve, a small west bank town, but they found no place suitable to store their trade goods. The commander of nearby Fort Chartres, on the east side of the Mississippi, allowed them to store their goods temporarily in his fort until they could find a permanent location. Laclède set up a temporary trading post in the nearby town of St. Anne de Fort Chartres. News of Laclède’s trading post soon spread to the local tribes, which began trading their furs and hides for Laclède’s goods.

Meanwhile, the war with Great Britain was not going well for France. Rumors circulated that France was to cede to Great Britain all of Canada and the French territory east of the Mississippi River, except for New Orleans. Laclède did not want to live under British rule, so in December, he set out with Auguste to find a site for his trading post on the west bank of the Mississippi River, where it would still be under French control.

Laclède found a site on high ground just below the mouth of the Missouri River. The location provided easy access for the upstream Missouri and Mississippi River tribes as well as for those that came down the Illinois River. After marking the site, Laclède returned to Fort Chartres for the rest of the winter.

Fort Chartres’ commander recommended to the French settlers on the east side of the Mississippi River that they return with him to New Orleans before the British arrived. Laclède told them that the move was unnecessary and convinced a number of people that the location of his new trading post would make an excellent town site.

On Valentine’s Day 1764, Laclède placed 14-year-old Auguste in charge of a work crew and sent them to the proposed site to begin clearing the land and building a trading post. When Laclède arrived in early April, he liked what Auguste had accomplished and named the trading fort St. Louis after the patron saint of Louis XV, the current king of France.

St. Louis’ settlers learned in December that France had transferred Louisiana to Spain in the secret Treaty of Paris two years before. Laclède and most of the settlers decided to stick it out and see what the new government would be like. Once again, Laclède’s instincts served him well. Spanish officials did not reach St. Louis until 1767, and most of them could speak French. Their governing rules for Upper Louisiana were little different than those of the French.

A Family Affair

After Laclède finished his combination home and trading post, he sent for Marie Thérèse and their other children. Laclède’s trading post was an instant success with the neighboring tribes. The Osages respected Laclède and his two sons, Auguste and Pierre. To cement that trust, the Osages invited the two boys to live with them. Auguste and Pierre spent long periods of time with the tribe, learning their ways and becoming their close friends.

Even though business with the tribes was booming, Laclède fell into debt. He was a good trader, but he was too willing to extend credit and allow late payments.

A directive from the government in New Orleans in 1774 further complicated Laclède and Marie Thérèse’s lives. René Chouteau had returned to New Orleans and, with the backing of the Spanish court, demanded the return of his wife. Marie Thérèse refused to go. Laclède did not want to send her back, so his friend, a St. Louis official, made excuses why Laclède could not return her to René.

The New Orleans officials did not attempt to force Marie Thérèse’s return, especially since René was a troublemaker and had recently been thrown in jail for falsely accusing a pastry chef of putting poison in his pastries. René’s demands finally ended with his death in 1776. With one less burden to shoulder, Laclède went about his business.

At age 49—and feeling ill—Laclède traveled to New Orleans in 1778 to compile a shipment of goods for his trading post. Before leaving St. Louis, he wrote a will disposing of his property. On May 27, he was returning upriver with the load of trade goods when he died of natural causes. His body was buried on the banks of the Mississippi River near the Arkansas Post in present-day Arkansas. Before Auguste could reach the grave site to recover Laclède’s remains for return to St. Louis, floodwaters washed away the body.

Auguste and Pierre eventually paid off Laclède’s debts and became successful businessmen in St. Louis, where they branched out from fur trading into mining and real estate. When France regained Louisiana from Spain, it sold the territory to the United States, a government that Auguste and Pierre wholeheartedly embraced. They opened their homes to Lewis and Clark when they visited St. Louis, and they supplied the explorers’ Corps of Discovery with provisions, guides and maps. As friends of the Osages, the Chouteau brothers were later instrumental in keeping the tribe on the U.S. side during the War of 1812. The brothers also provided leadership in St. Louis and Missouri Government and, above all, they stayed in the fur trade.

Most of the sons of Auguste and Pierre, as well as their nephews, continued trading fur. Pierre’s son, Pierre Jr., became a partner in and later bought the American Fur Company, which built trading posts and established a system of commerce throughout the Missouri River basin. Innovative, he was the first trader to send a steamboat—Yellow Stone—to the Upper Missouri River (in 1832, it went to Fort Union in present-day Western North Dakota).

The mixture of good business sense and honor that was shown by Laclède’s offspring made the Chouteaus one of the great families of the Old West.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy University of Nebraska Press from The American Fur Trade of the Far West, Vol. 2 –