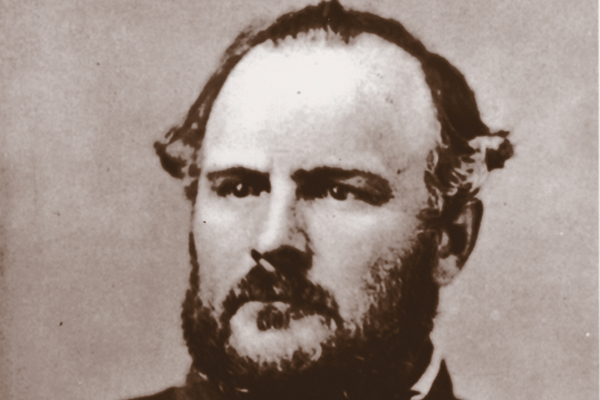

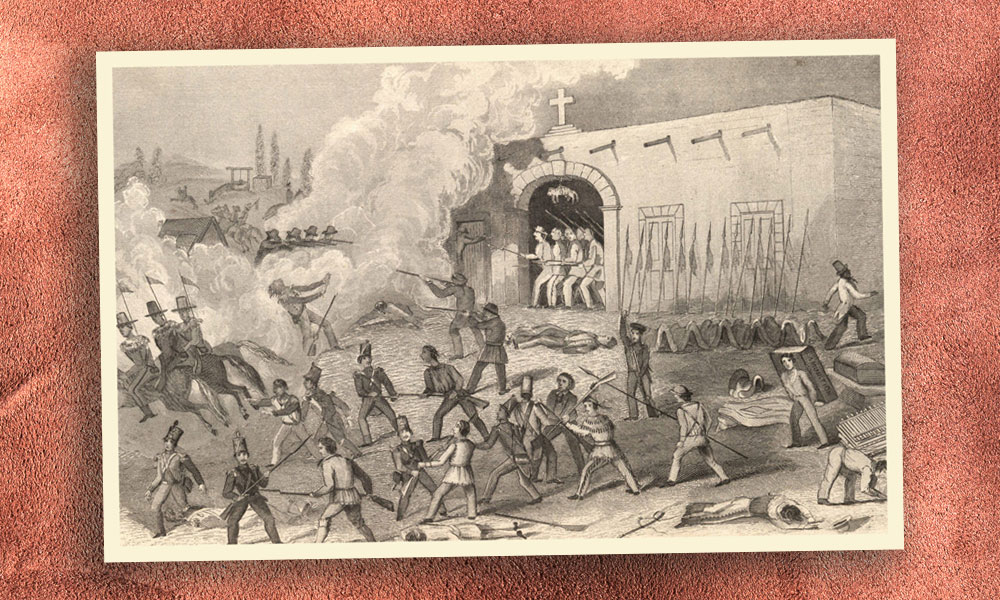

Just after dawn on November 29, 1864, elements of the First and Third Colorado Regiments commanded by Col. John M. Chivington attacked a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians camped beside a dry streambed known as Big Sandy Creek.

Just after dawn on November 29, 1864, elements of the First and Third Colorado Regiments commanded by Col. John M. Chivington attacked a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians camped beside a dry streambed known as Big Sandy Creek.

The ensuing battle—commonly known as the Sand Creek Massacre—left upwards of 150 mostly women and children dead . . . or so popular history would have us believe, a view put forth by Linda R. Wommack in “Take No Prisoners,” True West, Jan/Feb 2004.

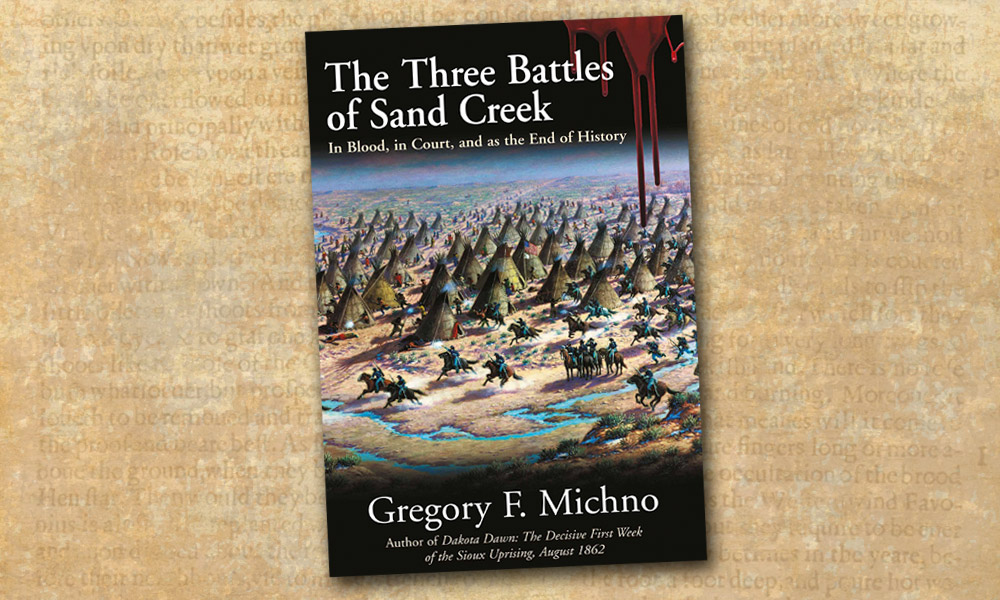

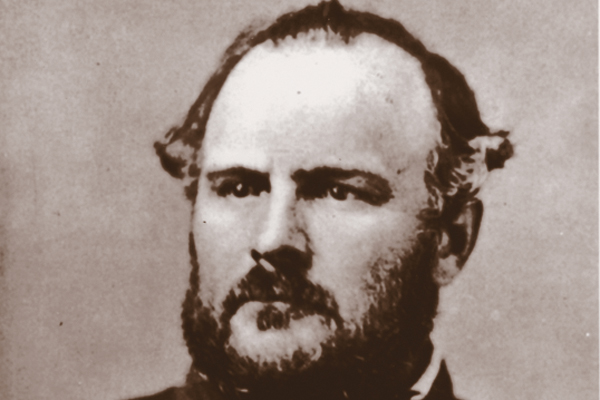

Writing “The Real Villains of Sand Creek” in the December 2003 issue of Wild West magazine, Gregory Michno presents a far different picture, arguing that the engagement was not a massacre, but rather was a tough fight in which the Indians, though suffering a defeat, acquitted themselves well. Michno points his finger at Maj. Edward Wynkoop, who disobeyed standing orders by trying to make peace with the Indians and instead placed them in harm’s way. Afterwards, according to Michno, the major publicly characterized the fight as a “massacre” in order to exonerate himself of any fault.

In contrast, Wommack lays the blame for the battle at the feet of Chivington and Colorado Territorial Gov. John Evans, who ordered the colonel to “Go in pursuit of all hostile Indians … kill and destroy.”

True West asked both authors to present their positions and show why the other one is wrong. Linda R. Wommack is a Colorado-based writer, who is currently working on a Rocky Mountain PBS documentary about Sand Creek. Gregory Michno, also from Colorado, has recently completed a history of the fight, Battle at Sand Creek, to be published this spring, wherein he hopes to dispel the popular, “politically correct” notion of the battle.

Their face-off begins…

Wynkoop Was Not at Fault.

By Linda R. Wommack

In a speech given years after the 1864 atrocity, John Chivington said “I stand by Sand Creek.” Right or wrong (and I believe he was wrong), he stood by his convictions. I, too, stand by my research and articles regarding Sand Creek.

The Colorado Territory Plains had been ravaged by radical Cheyennes and Arapahos during the summer of 1864. The citizens were in a state of panic; communications to the East had been cut, stage lines were stopped, wagon trains were terrorized. Supplies were also nonexistent and prices soared. The citizens demanded Gov. John Evans take action.

“Help Demanded From Government,” “Appeal To The People,” “Cavalry or Infantry” were just a few of the many headlines screaming for action in Colorado’s newspapers.

Evans found himself in the middle of a political pressure cooker. The safety of Colorado’s citizens and secured land prospects would lead to eventual statehood. He clearly needed a military victory against the Indians, for the sake of the citizens, as well as his political future. Evans found his answer with the newly enlisted Third Regiment of Colorado Volunteers and his ally, Col. John M. Chivington, a Civil War hero and proponent of statehood, who was now the military commander of the District of Colorado.

The final stage was set when Evans declared martial law, issued a proclamation for the citizens to defend themselves and implored Chivington to “eradicate the Indian problem.” Chivington, seeking military fame, put forth a plan of annihilation.

Working for a peaceful solution, Maj. Edward Wynkoop, commander of Fort Lyon, brought the Cheyenne and Arapaho chiefs, including Black Kettle, to Denver where Gov. Evans held a cold reception. Chivington informed the chiefs that peace negotiations were to be made “when you lay down your arms … for treaties has passed.” Wynkoop returned to Fort Lyon, where he instructed the Indians to camp at Sand Creek, within Fort Lyon’s district, ensuring their safety. Wynkoop’s belief in peace, while continuing his military command, makes him at the very least a victim of circumstances, and thereby caught in the middle.

To think Wynkoop’s actions were the cause of the atrocity is irrational, based on the facts and testimony that followed at the Congressional hearings of 1865. Chivington had resigned his commission with no military charges, but he was further condemned for his actions. Governor Evans was removed from office by the U.S. district attorney. Wynkoop, on the other hand, went on to serve as a distinguished military officer, continuing to fight for peace.

Yes He Was.

By Gregory Michno

The crusaders, politicians, committees and press gave Sand Creek bad reviews from the start. Eyewitnesses who saw the event as a hard-fought battle were later called apologists or liars by historians and novelists. The Sand Creek affair was not a stellar event in American history, but the fight and the people involved did not get a fair hearing.

The episode has been depicted as an epic battle between good and evil—a simplistic explanation that will not stand up to historical scrutiny. The traditional view places the blame on Gov. John Evans and Col. John Chivington. Although some relish conspiracy theories, Evans and Chivington did not hatch a secret plot to massacre Indians.

A study of primary evidence, combined with archaeological discoveries and an open mind, will lead us to more accurate conclusions. The village did not rest on the traditional site, as archaeological finds prove there was no significant fight in the village. The Colorado volunteers took serious casualties. Of the 1,470 engagements in the trans-Mississippi West from 1850-90, the soldiers suffered greater losses in only six other battles, making Sand Creek more costly to the whites than 99.6 percent of the other battles.

With this new information, some traditional heroes have proved to be gilded, not golden. The person most responsible for the Sand Creek incident was Maj. Edward Wynkoop. He may have had good intentions, but were it not for his continual violation of orders, there never would have been a battle. His attempt to make a separate peace with the enemy while his own army was trying to bring them to battle should have resulted in his own court-martial. To cover up his mistakes, he frantically shifted the blame.

Although Wynkoop set the stage for the tragedy, the Indians must also accept responsibility. They had been raiding and killing for years. If some now favored ending the war, it did not absolve them of guilt. Had they not captured seven white prisoners, they never would have written the letter to Wynkoop, in which they dangled the hostages as pawns to bargain for peace. Placed in a 21st-century context, Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle harbored terrorists, and in so doing, he was not immune from attack.

The depiction of Sand Creek as a massacre stems from the machinations of a handful of men: Sam Colley, John Smith and Wynkoop. All did their best to exaggerate and obfuscate so they could hide their mistakes, gain monetary advantage or seek revenge. The finger can also be pointed at Maj. Scott Anthony (Wynkoop’s replacement) for deceiving the Indians as to the military’s intentions, and certainly at Chivington for not controlling the excesses of his men.

But, if one must choose a new villain, it is Wynkoop. Without his interference, we would not be writing of this battle today.