Enforcing the law in the early West was a vocation for stout, fearless men.

Enforcing the law in the early West was a vocation for stout, fearless men.

And yet there were at least three who extended the long arm of the law to apprehend malefactors, even after they had only one arm to extend.

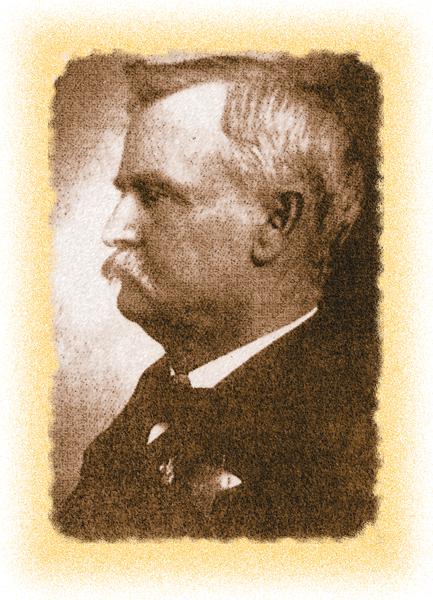

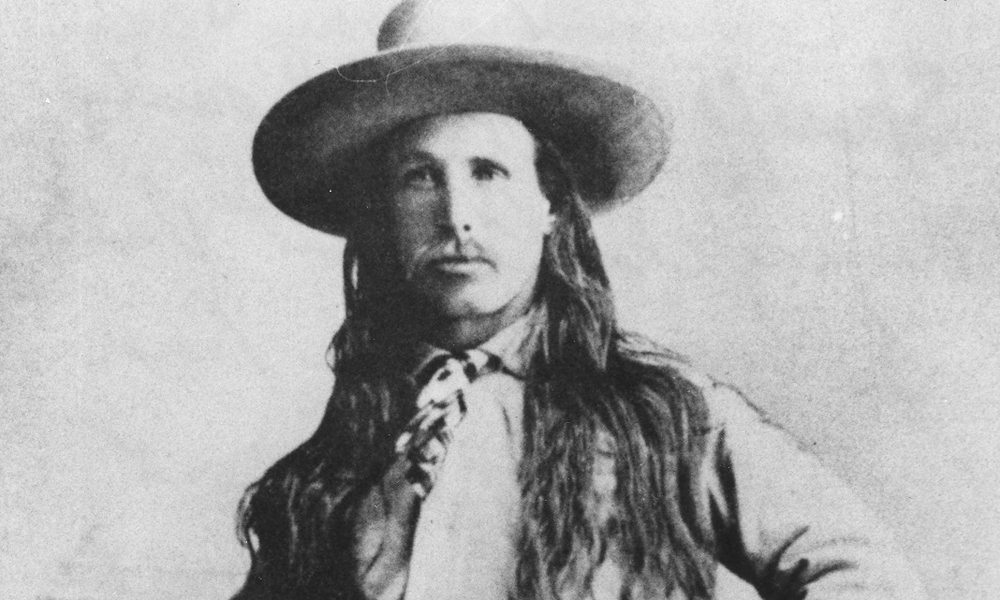

Virgil Earp was the most famous of the three because of his brother Wyatt and his own participation in Tomb-stone’s fabled “Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.” Born in Kentucky in 1843, Virgil was the eldest of the “Fighting Earp Brothers.”

After the Civil War in which he fought as a Union soldier, Virgil crisscrossed the frontier, working as a teamster, stagecoach driver and railroad laborer. Although he claimed to have pinned on a badge in Wichita and Dodge in the mid-1870s, no confirmation has been found.

His first documented encounter as a peace officer was in Prescott, Arizona, in October 1877, when he was deputized to help arrest desperadoes Tallos and Wilson. In the ensuing gunfight Tallos and Wilson were killed, and Virgil Earp acquitted himself well. The incident led to his appointment as a night watchman and his election as a constable in November 1878. A year later, he was appointed deputy U.S. marshal for Pima County, and moved to Tombstone. In 1880 he also became the Tombstone city marshal and stepped into the war between his brothers and the Cow-boys. On December 18, 1881, less than two months after the famous gunfight, bushwhackers blasted Virgil with shotguns as he made his nightly rounds. One pellet struck him “just above the groin, coming out near the spine,” but his worst injury was a shattered left arm. Doctor George Goodfellow, an expert at treating gunshot wounds, saved the arm from amputation, but had to remove the elbow and almost six inches of bone above the joint. “Never mind,” Virgil told his distraught wife, Allie. “I’ve got one arm left to hug you with.”

Sometime later Virgil opened a detective agency in Colton, California, where voters elected him constable in 1886 and city marshal the following year.

By 1904 the mining excitement at Goldfield, Nevada, attracted Virgil, and he accepted appointment as Esmeralda County deputy sheriff and acted as a special officer at the National Club, a saloon and gambling house. More than 60 years old, in failing health and with only one good arm, the aged lawman could still handle saloon toughs and troublemakers. Goldfield was Virgil Earp’s last boomtown, for he contracted pneumonia and died on October 19, 1905.

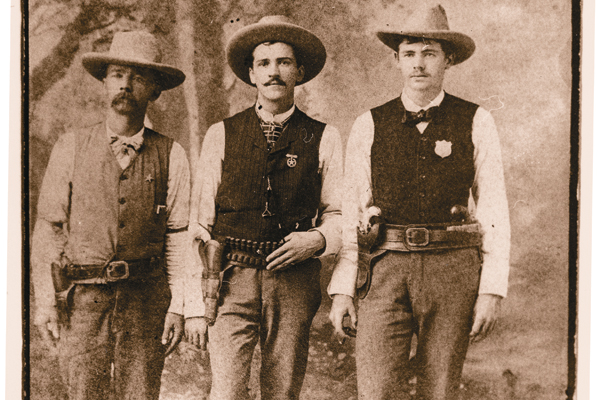

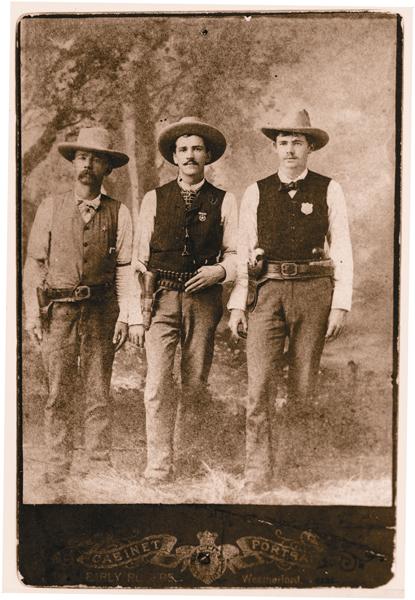

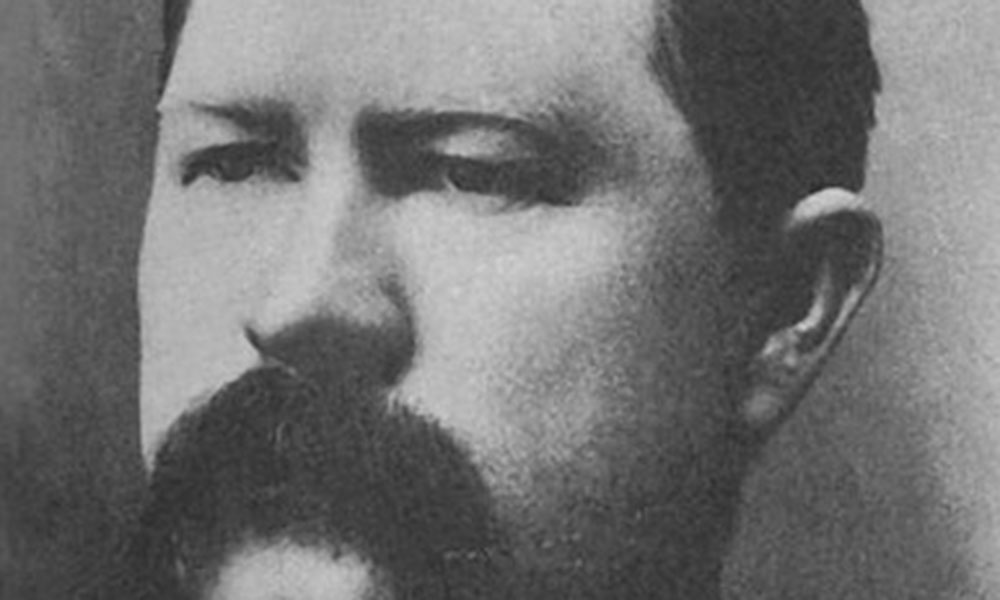

Another career lawman was Edward W. Johnson, born in Clark County, Arkansas, in 1853, who took his first law enforcement post at the age of 22 when he became a deputy sheriff in Arkadelphia. After moving to Clay County, Texas, in 1880, Johnson became a deputy under Sheriff G. Cooper Wright, who was just beginning a 14-year tour as the county’s top lawman. When Democrat Grover Cleveland became president in 1885, he appointed loyal party supporter William Lewis Cabell as U.S. marshal for Texas’ Northern District. Cabell, in turn, chose experienced Democratic lawmen as deputies, including Ed Johnson, who was assigned to work out of the federal court in Graham.

In late February 1888, Johnson led a posse after outlaws in the Indian Nation. Stopping in Wichita Falls to spend the night, he argued with local cowboy Frank James. After exchanging hot words at the Bender Rooming House where Johnson had taken lodging, James left, but returned moments later carrying a Winchester. When Johnson saw him, he jerked his pistol. Both men pulled their triggers, and the reports from the rifle and six-shooter sounded like one. Shot through the heart, James staggered 20 steps before collapsing and breathing his last. Johnson had been struck in the right forearm, the bullet smashing the bones, severing the artery and passing through 30 pages of documents before coming to rest in a pocket memorandum book. Bystanders carried him to the Commercial Hotel where Doctors Coffield and Burnsides worked feverishly to stop the bleeding. According to one newspaper, “the floor of the room he was in looked like they had been killing hogs.” They amputated his arm on Leap Year’s Day.

A routine arrest by Johnson only six months after losing his arm set off a chain of events that would profoundly effect his life and bring national attention to Graham and Young County. Central figures in the affair were the Marlows, five frontier-hardened brothers: Charley, George, Boone, Alf and Lewellyn (nicknamed Epp). For years the Marlows had eked out a living from the land in Texas, Colorado and the Indian Territory. Some said they had not always done it honestly. Holding an arrest warrant for the brothers for stealing Indian ponies, Johnson led a posse into the Indian Territory. He apprehended four of the Marlows—George could not be found—and brought them back to Graham. When George came to town a few weeks later, he quickly joined his brothers in jail. Released on bail, the brothers soon plunged into deeper trouble. Boone shot and killed Sheriff Wallace when he attempted to arrest him on a murder warrant from Wilbarger County. Boone fled, but county officers rounded up the other brothers and put them back in jail.

The Young County citizenry was outraged by the murder of their popular sheriff, and on the night of January 17, 1889, a band of armed men burst into the jail, intending to lynch the Marlows. When one member of the mob attempted to enter the cell, Charley Marlow struck him so hard he later died from the blow. The brothers’ resistance unnerved the lynch mob and they dispersed.

Recognizing that his prisoners were in grave danger in Graham, Johnson arranged to transfer them to Weatherford. After nightfall on January 19, the four Marlows and two other federal prisoners, W.D. Burkhart and Louis Clift, started for Weatherford under heavy guard. They were paired with leg shackles: Charley and Alf, George and Epp, Clift and Burkhart. At Dry Creek, two miles out of town, a large number of masked men attacked the procession, guns blazing. The Marlows tumbled from their wagons and grabbed their guards’ weapons. Soon the mob, guards and prisoners were firing wildly. When the battle was over, three members of the lynch mob and two Marlow brothers lay dead. Several others were wounded, including the remaining Marlow boys and Deputy Marshal Ed Johnson, who had taken a bullet in, of all places, his only hand.

Charley and George Marlow escaped. Suffering from their wounds, they eventually surrendered to federal officers. Bounty hunters killed fugitive brother Boone. The bloody affair at Dry Creek led to lengthy criminal trials that were appealed to the Supreme Court.

Ed Johnson’s wounded left hand finally healed, but he lost his job as deputy U.S. marshal. He stubbornly refused to leave Young County, though many residents blamed him for the tragedies that had befallen their community. In 1911 Johnson again pinned on a lawman’s badge, accepting appointment as a deputy under Sheriff O.H. “Ol” Brown. At the age of 63, Johnson moved to California where he served 15 years as a deputy sheriff in Los Angeles County. He died in the early 1930s.

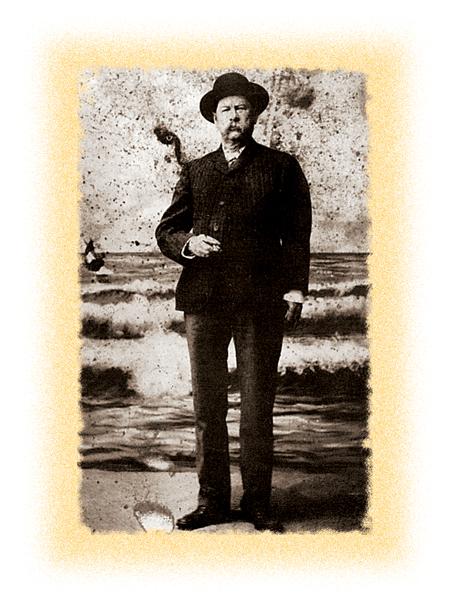

A third one-armed lawman came to the profession by way of outlawry, a common occurrence in the frontier West. Jesse J. Rascoe was born July 10, 1848, in Rusk, Texas. Like many other Confederate sympathizers, he was drawn into anti-social behavior by the violent sectionalism of the Civil War and the corrupt Reconstruction that followed. He was living with his parents near Corsicana, Navarro County, Texas, when family tradition says 17-year-old Jesse became infuriated when a black Union soldier pushed his mother off a sidewalk, breaking her ankle. In a campaign of retaliatory vengeance, so the story goes, he waylaid and killed several black soldiers. Though short-tempered and violent, Rascoe was a devoted family man. His marriage to Mary Jan “Mollie” Duncan in 1866 lasted more than a half century and produced eight children.

In August 1874, he killed a black man and stabbed another one in the arm. His second victim appears to have also died, for on March 18, 1875, two first-degree murder indictments were brought against him in Navarro County. Released under $1,500 bond to await trial, he skipped to Louisiana, perhaps with the help of his brother, William Perry Rascoe, a Texas Ranger.

Records do not indicate that Rascoe ever came to trial for these murders. But it did not take him long to leap back into the legal fire with the killing of Harry Lackey in Corsicana, Texas, on December 29, 1877.

The killing had been committed before the startled eyes of two law officers, a city policeman and a deputy sheriff. Yet, Rascoe escaped. The Texas governor offered a $500 reward for his capture, $300 to be paid on his delivery to Navarro County, and $200 upon his conviction. In May 1878, Rascoe’s $1500 bond was forfeited.

Two years later, Rascoe was confined in the county calaboose in Corsicana, but again his Texas Ranger brother came to his aid. Bill Rascoe concealed a saw blade in a pair of new boots and delivered them to Jesse, who quickly sawed his way to freedom. So says the family.

However he accomplished it, Jesse Rascoe did break jail at Corsicana and headed to Mexico and then Arizona Territory. By 1882 he was working for John Galey of Galeyville in Cochise County, using the alias Peavey House. He later rode for the 3C cattle spread.

Galeyville and Charleston, satellite camps outside Tombstone, were notorious hangouts for outlaws on the run, and it was in Charleston that Jesse Rascoe, a.k.a. Peavey House, suffered the gunshot that took his arm. He had come to town on March 5, 1882, to collect some back wages. In typical fashion after drawing his pay, he raised a bit of hell in a saloon and drew the ire of a tough bartender. Rascoe had left the place and was preparing to mount his horse when the barkeep, scattergun in hand, followed him outside and turned loose his battery, shattering Rascoe’s right arm with lead pellets. Cowboy friends took the severely injured man to Tombstone, where a doctor (probably George Goodfellow, who had worked on Virgil Earp’s shotgun-blasted arm only weeks before) amputated Rascoe’s arm at the elbow. He was not expected to live, but like Virgil Earp before him and Ed Johnson years later, he refused to die.

Reports of the shooting reached Texas, where officers concluded that the man known as Peavey House in Arizona was the missing Navarro County fugitive Jesse Rascoe. At the request of County Attorney Rufus Hardy and County Judge R.C. Beale, Texas Governor Oran Roberts issued a requisition for Rascoe’s return for the murder of Harry Lackey, “a most cowardly and dastardly act,” in the words of Hardy.

Rewards for Rascoe were still outstanding, so bounty hunter Jack Duncan of Dallas went to Arizona, took the fugitive into custody on April 3 and brought him back to Corsicana. A newspaper reported that Rascoe acknowledged killing Lackey and also confessed to “several other murders in Texas, mostly negroes.” He was, said the paper, “undoubtedly a hard case.” Rascoe was jailed in Corsicana until his trial for the Lackey murder the following August. Despite the assertion by County Attorney Hardy that the proof of Rascoe’s guilt was “easy to come at and positive,” witnesses to the crime disappeared or refused to talk, and he was acquitted.

Perhaps this close brush with the hangman’s noose scared Rascoe, for thereafter he seems to have renounced the life of a saloon tough and outlaw. In 1889 he settled in the new town of Eddy, New Mexico. He had always made friends easily, and he soon became quite popular. He ran for constable at the first elections held in Eddy in January 1890 and easily defeated his opponent, W.L. Goodlett, a deputy sheriff. Rascoe and Goodlett were friendly and worked well together as lawmen, but a few months after the election, Rascoe had the unpleasant duty of arresting his fellow officer for participating in the killing of an accused horse thief named Cofelt.

He was successful in the tough town of Eddy and later moved to Roswell, where he served as city marshal from 1904 to 1908. He was paid only $55 per month, but license fee collections and a share of police court fines more than doubled his income. Highly respected in Roswell, he was elected an officer in the Old Settlers Society of Chaves County in 1905.

One old townsman remembered him well: “In performing his duties in Roswell, he always rode a very fine sorrel horse. He had scabbards strapped to either side of his saddle. In one he carried a sawed-off, double-barreled, 12-gauge shotgun; in the other he had a Winchester .30-30 repeating rifle, known to old-timers as a ‘saddlegun’ because it had a shorter barrel. Around his waist he wore a cartridge belt, always completely filled. On his left hip, because his right arm was missing, he wore a regulation double-action Colt .45.”

Ill health and advancing years forced Rascoe to retire in 1908. He moved to Bakersfield, California in 1911. His wife died in 1922 and on January 25, 1925, Jesse Rascoe, deadly Texas gunman-turned-honorable-and-efficient-one-armed-peace-officer, followed her to the grave. He was 76 years old.

Robert K. DeArment, World War II veteran, author of several books and member of NOLA since 1979, is also a contributing editor to True West. He lives with his wife, Rose, in Sylvania, Ohio.

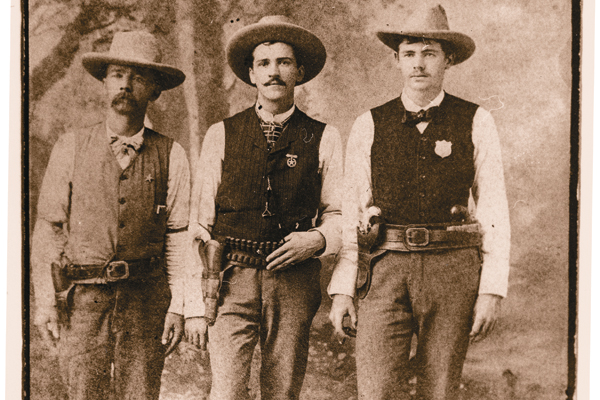

Photo Gallery

– Author’s collection –

– Courtesy George T. Jackson, Jr. –

– Craig Fouts collection –