They were so bold, so brave and so bodacious that their journey would not only be America’s first great expedition, but also its most important one until man walked on the moon 165 years later.

They were so bold, so brave and so bodacious that their journey would not only be America’s first great expedition, but also its most important one until man walked on the moon 165 years later.

It’s impossible to talk about Lewis and Clark without using superlatives: the first, the best, the longest, the only. Even historians who report the halos and warts alike can’t help themselves. Stephen E. Ambrose’s bestseller on the thousand-day, 8,000-mile odyssey is titled Undaunted Courage.

They were part of the greatest national expansion the world would ever see. In one fell swoop, with $15 million, the small United States doubled in size and added 565 million acres from the Mississippi to the Rockies.

President Thomas Jefferson was hell-bent to find all that existed in his Louisiana Purchase. He wanted to lay claim to the land he’d bought, as well as land farther west to the Pacific. But most of all, for him and the Congress that thought it was paying $2,500 for the “Voyage of Discovery”—but ended up with a final bill of $38,722.25—this was a business trip.

Jefferson and the nation believed totally in the magic Northwest Passage: a river route from the Pacific to the Eastern markets. Oh, how it would increase profits on goods from the Far East, eliminating the tedious and lengthy trip around the tip of South America. What riches this route would mean to the new nation—all Lewis and Clark had to do was find it and map it.

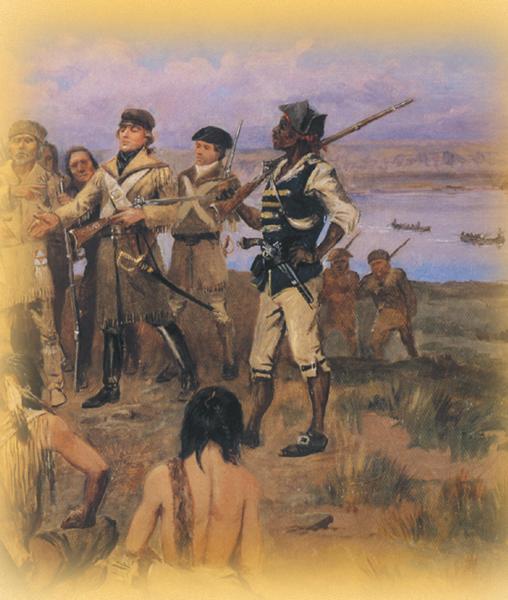

While they were at it, their military mission would solidify relations with the tribes that should be trading only with the “White Father” back East, not the French and British who had been coming down from Canada.

So off they went, setting foot where no white man had ever trod, forging into a land that was little more than blank space on every existing map. Always they proceeded onward, helped by tribes they encountered along the way—often surviving only because of those friendly people—and faced hardships that should have turned them back. They were out of touch with “civilization” so long, most Americans thought they’d perished.

With a license that seems so very American, they named things as they went. “Judith River” was named in honor of Miss Hancock, who’d become Mrs. William Clark when her fiancé returned from his adventure; and the giant legendary bear they’d heard so much about became the “grizzly bear.”

They kept copious notes on everything they saw, everything they experienced. Besides the captains, some of the enlisted men also kept journals. In all, a million words would be written by quill pen with reconstituted powdered ink on parchment paper stored in leather pouches. The journals give an instant snapshot of the West, often with spelling that is as confusing as it is bemusing. (“Fearless spellers,” Time magazine called them.)

The enormity of what they’d discovered—what myths they’d debunked, the 122 new animals and 178 plants they’d found—wasn’t immediately apparent upon their return in September 1806. Of course, there was that little problem of failure—they’d been sent to FIND the Northwest Passage, not come home with evidence it didn’t exist. President Jefferson did his best spin ever by simply changing the trip’s objective: the men had spent 28 months understanding the 58 tribes they encountered and collecting trunks of plant and animal specimens.

The incredible journals that had been kept, which Lewis was charged with editing, never were published in his lifetime. He died just three years after his return, apparently by his own hand. He was 35.

Clark then took up the task of editing, and the journals were finally published in 1814. But they weren’t a hit, and wouldn’t become significant until subsequent publications almost a century later caught the attention of a nation watching the West being “settled” and mined and ranched by the second and third wave of white explorers.

With the commemoration this year of the 200th anniversary of the Voyage of Discovery, every point along the trail is hoping more and more Americans will discover the magic.

There is much to celebrate, but also much to bemoan. Although Lewis and Clark came in peace—handing out medals that showed the united hands of whites and natives—they were about the last white men who didn’t see the Indians as simply in the way. Those who came after Lewis and Clark brought diseases that wiped out entire tribes, guns that killed whole vill-ages and policies that robbed the natives of their lands and relegated them to reservations. The white man thrived, but only as he destroyed the red man.

As the bicentennial is celebrated, those stories must also be told. For all Americans—both those who are native-born and those of us who came later—Lewis and Clark signify a plate shift in American life.

Theirs was a journey that changed America forever.

When Lewis and Clark reached North Dakota, they found the most cosmopolitan area they’d ever encountered.”

Certainly, Patrice Tunge must be exaggerating. The communications coordinator for the North Dakota Lewis & Clark Interpretive Center is sitting in her office overlooking the Missouri River.

Rural is the best word to describe her view: some plowed fields, a few farmhouses dotting the rolling hills and, of course, cottonwood trees bordering the meandering river—nothing that would conjure the idea of cosmopolitan in a state where most places look like this and that word is seldom spoken.

But in October 1804 when the explorers arrived, there was a big city along this river: five noisy, crowded villages with as many as 5,000 inhabitants that was already a regular stopover for traders of a half-dozen nationalities. So surely she must mean they hadn’t seen anything like this since they began their Voyage of Discovery.

But that’s not what she means at all. She means exactly what she said. The villages of the Mandan and Hidatsa tribes were larger and healthier than the nation’s capital of Washington D.C., where an anxious President Jefferson awaited word on exactly what he’d bought for the $15 million he spent on the Louisiana Purchase. They were larger and more prosperous than St. Louis, near where the expedition had begun five months earlier, and they were teeming with an ethnic stew you wouldn’t find in the “civilized East”—Native American, French, German, Spanish, Welsh, French Canadian, English.

But it wasn’t just the size and mix that made such an impact. Even more impressive was the incredible commerce centered here. For over 900 years, this had been a trading center. “It was the original Mall of America,” Tunge says.

As historian Stephen E. Ambrose puts it, “Nowhere else could one see at a single glance the diversity and colorful lifestyle of the Indians of the Plains. There were Spanish horses and mules to buy and sell, fancy Cheyenne leather clothing, English trade guns, baskets of produce, meat products, furs of all kinds, musical instruments, blankets, dressed buffalo hides, painted buffalo hides.”

The expedition would spend one-fourth of its entire trip in North Dakota, living among these people who called them friend, and who they honored by naming their winter home Fort Mandan.

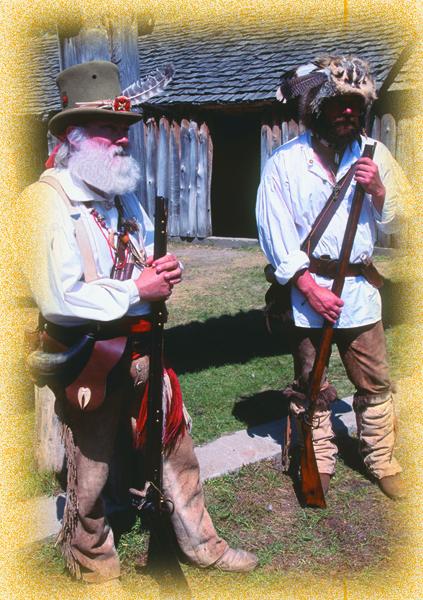

It was here that the motley crew of soldiers, frontiersmen and boatmen—already a disciplinary problem with insubordination, brawling and drunkenness—would become a band of men who covered each other’s backs. “The best of families,” Lewis called them. As history tells us, “They gradually learned the lesson of community.”

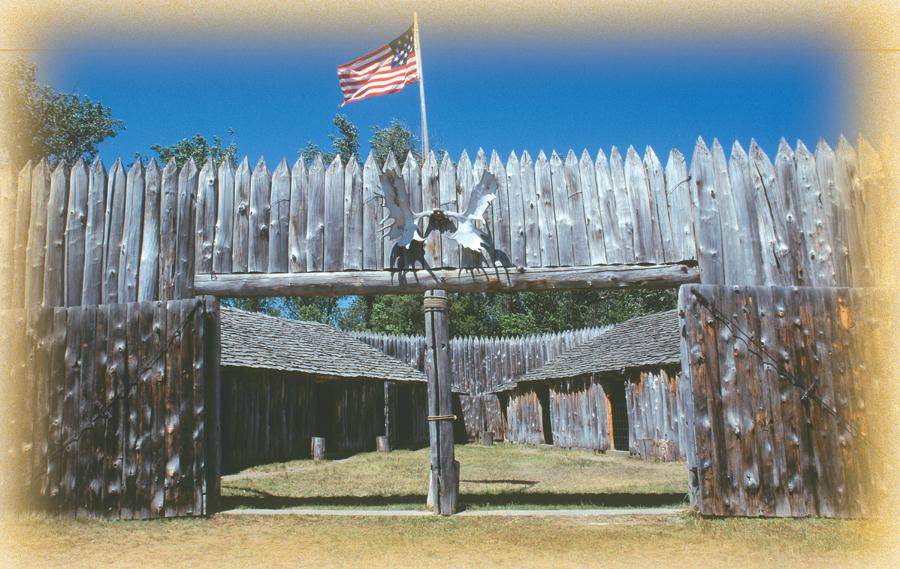

In the entire 7,689-mile trip they’d make camp over 600 times, but nothing so resembled “home” as Fort Mandan. The men built the trapezoidal fort with its 18-foot outer log walls in just two months, finishing on Christmas Eve. By then, they’d already tasted a bit of the bitter North Dakota winter—on December 17, it had hit an astonishing 45 degrees below zero; in all, they’d awaken to 49 mornings when the temperature was below zero. It would be the coldest winter any of them had ever known, probably would ever know. No wonder the stone fireplaces that kept each of the 10 rooms warm were a center-piece of their lives.

They first hoisted the American flag with its 17 stars on Christmas morning, then spent the day drinking whiskey, singing and dancing to a fiddle. The liquor and a day of rest were their only Christmas gifts. There was no Christmas tree, for the German settlers who’d bring that tradition to America hadn’t yet arrived.

Most significantly, the expedition’s five months at Fort Mandan would be crucial to the explorers’ survival. “The Native Amer-icans taught them how to survive off the land,” Tunge re-counts. “They came to North Dakota in linen coats—you can’t survive winter like that.”

They spent the long months on buffalo hunts with their Indian neighbors (during the entire expedition, they’d kill 259 of the beasts that then numbered in the tens of millions). They made pair after pair of moccasins. They learned how to make candles from buffalo fat, and indeed, when they almost starved to death later in the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana, they ate the candles to keep themselves alive. And they consumed 6,000 calories a day from the wildlife they killed and the beans and squash the Indians traded.

Historians agree that without the food from the tribes, the men would never have survived the winter. (When fresh meat wasn’t available, they got a taste for dog. Lewis would come to prefer it to elk or venison, but Clark never developed a taste for canine.)

And of course, it was at Fort Mandan that the explorers first met Sacagawea, who joined their voyage as an interpreter with her French-Canadian husband. They lived in the room next to Lewis and Clark’s that winter, across the courtyard from the other men, who were stuffed seven or eight in 14-foot-square rooms. On the floor of her quarters, Sacagawea gave birth to her first son with the help of Lewis, who fed her the rattle of a snake to induce labor. She’d carry the infant Clark nicknamed “Pomp” on a cradleboard across the Rocky Mountains all the way to the Pacific and back.

Except for Christmas Day when the captains asked for privacy, the fort was visited daily by Indians. Some brought sick children to be treated by the nice Captain Lewis; others came for the blacksmith or to exchange information, or to trade for the precious blue trade beads that were so popular with the women. The men were busy even without visitors. They exercised daily to keep fit, hewed canoes from cottonwood logs, made buffalo jerky, continually cooked in their copper pots, took turns standing guard and got regular treatments for syphilis.

By the time they left Fort Mandan on April 7, 1805, they were a cohesive group ready to “proceed on” to find the wonderful “Northwest Passage.” As historian Dayton Duncan puts it, belief in the Northwest Passage was “the principal myth of North American geography for hundreds of years.”

It would be months before Lewis, confronted with the never-ending Rocky Mount-ains, realized they were searching for something that just wasn’t there.

On their return trip to North Dakota from the Pacific, only Clark would go back to see what had become of Fort Mandan, “to view the old works,” as he so unemotionally called it. He found most of the fort gone, having burned down by accident. But this wooden stockade along the Missouri would always hold a special place in their story of discovery.

Although the original site is now thought to be under-water, in 1971, a replica fort was built on the banks of the Missouri near Washburn, North Dakota.

To this day, the state advertises Fort Mandan with billboards telling a simple truth: “Lewis and Clark slept here 146 times.”

Jana Bommersbach is one of Arizona’s most acclaimed journalists, having won major accolades for her many-faceted career. She’s been Arizona’s Journalist of the Year; named the nation’s best columnist for a city magazine; earned a regional Emmy for her television work; and in 2002, won more awards from the Arizona Press Club than any single journalist in the state. She’s also an author, whose debut book, The Trunk Murderess: Winnie Ruth Judd was cited as one of the country’s best nonfiction books of 1992. Jana grew up in North Dakota, but has made Arizona home for 30 years—a “born again native,” as it were. She recently joined True West as the Special Projects Editor.

Photo Gallery

– Painting By Charles Russell –

– Photo By Karen A. Robertson –

– Photo By Karen A. Robertson –