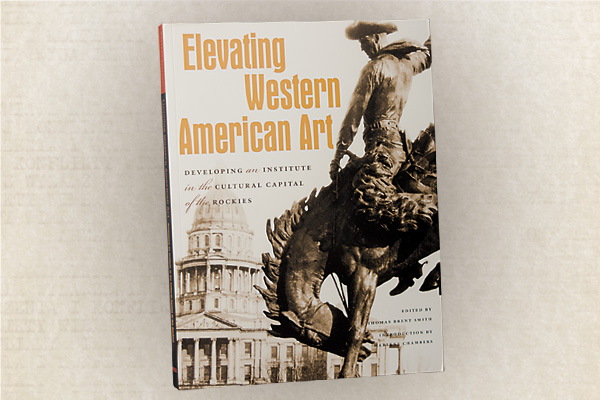

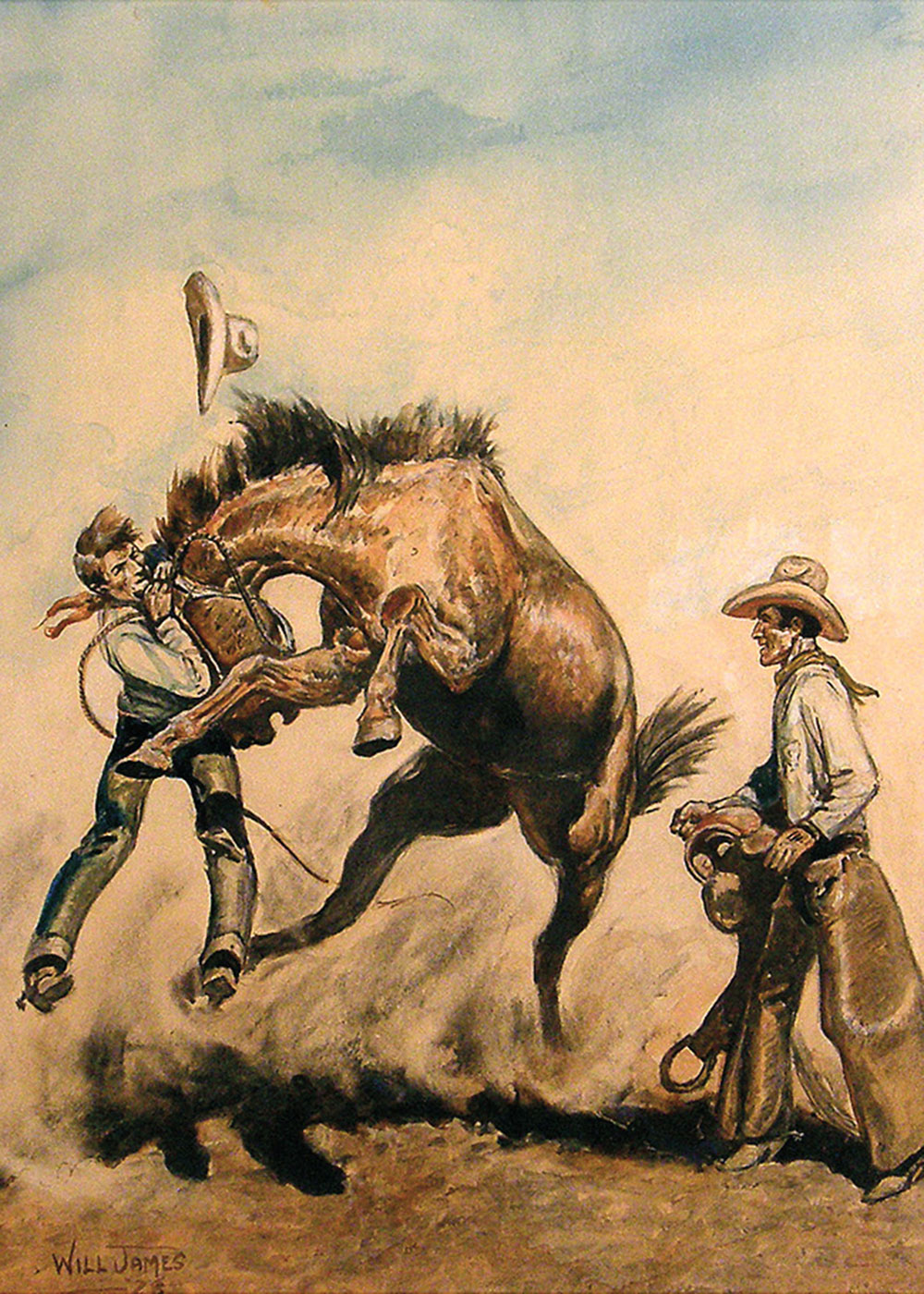

— Courtesy Whitney Western Art Museum, BBCW, Cody, Wyoming, Gift of General Budd Marks. 2.71 —

Painting and illustration cannot be mixed—one cannot merge from one into the other,” Western artist/illustrator N.C. Wyeth said.

Yet Wyeth (1882-1945) made a career doing both, leaving a legacy and a record of the American West.

What’s the difference between an artist and an illustrator?

“An illustrator usually had to take orders from an editor, like ‘Turn the horse around and make him go the other way,’” says Forrest Fenn, an art historian in Santa Fe, New Mexico. “The illustrator hated that worse than anything, but at least it was a living. Ernest Blumenschein [1874-1960] was a good example. In the process of being over-supervised, the illustrator learned discipline and what the consuming public wanted to look at. So, it was natural for him to become a fine art painter. Clark Hulings [1922-2011] was a good example, but he always cussed the editors.”

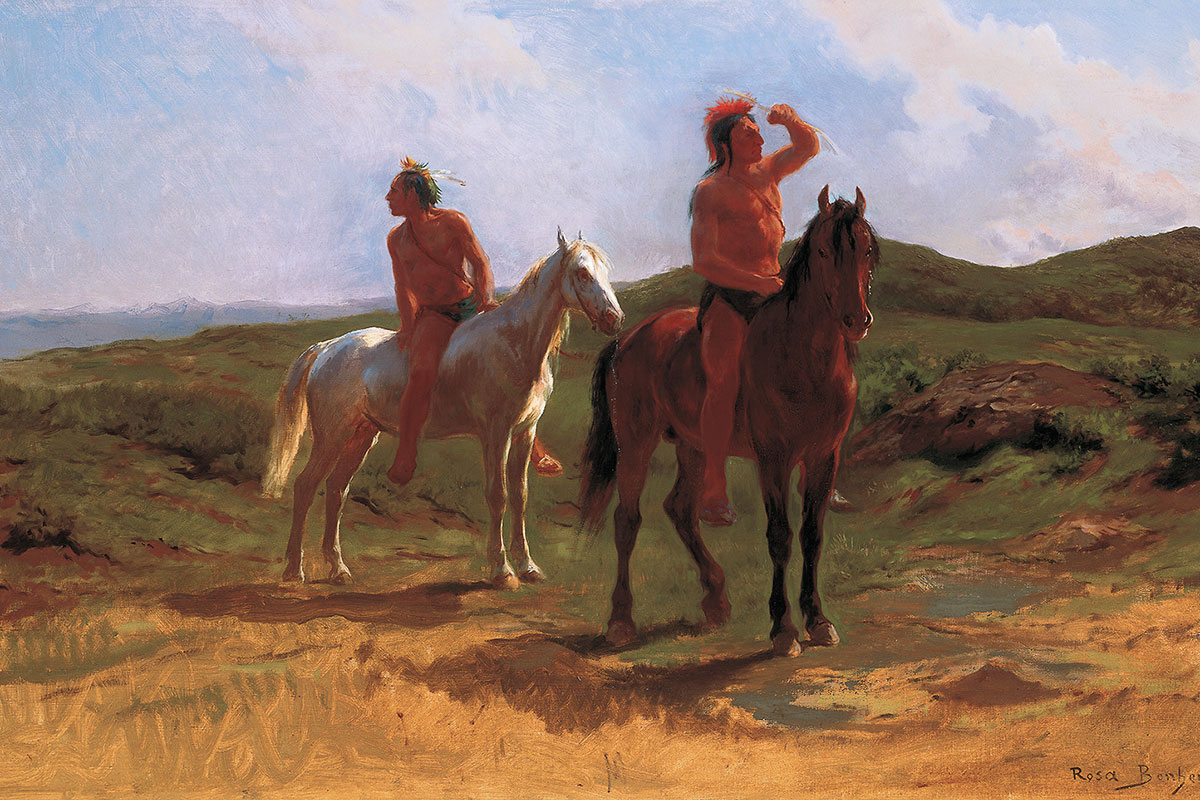

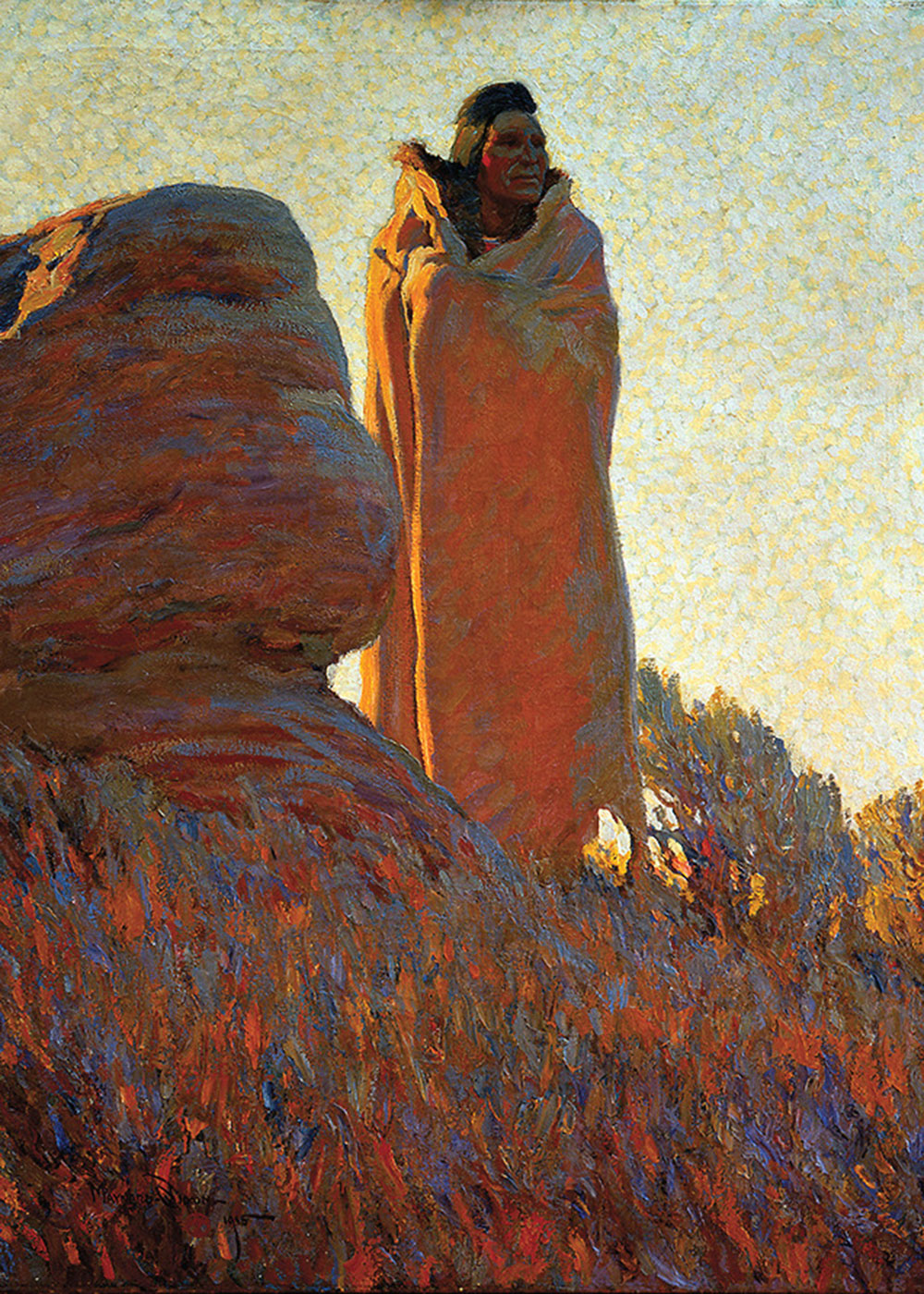

— Courtesy The Whitney Western Art Museum, Buffalo Bill Center of the West, Partial Bequest of Vernon R. Drwenski and Museum Purchase, 8.04.6 —

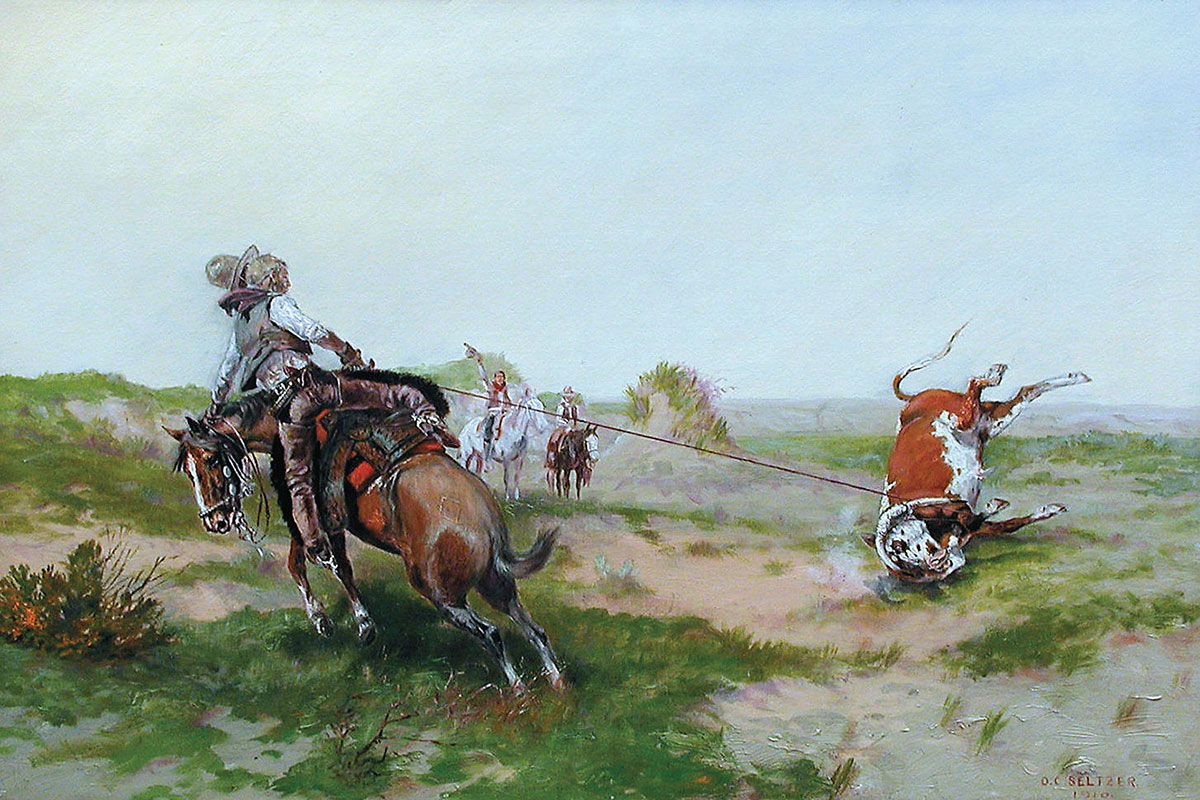

George Caleb Bingham (1811-1879), Alfred Jacob Miller (1810-1874), John Mix Stanley (1814-1872), Charles M. Russell (1864-1926) and Frederic Remington (1861-1909) were great artists—but also great illustrators.

“The common theme for these artists—even Remington, in many instances—is that they observed firsthand what they painted and distributed their work through illustrated books or journals, or, in the case of Bingham, in individual lithographs and engravings, with the intention of documenting an individual, event, process, or place,” Ron Tyler writes in the introduction to Western Art, Western History: Collected Essays.

Early artistic documentarians included John James Audubon (1785-1851), George Catlin (1796-1872), Albert Bierstadt (1830-1902) and Thomas Moran (1837-1926), whose works revealed European influences.

By the turn of the century, Western art had become truly American art—with American influences. Russell likely had the most influence.

— The Booth Museum, Cartersville, Georgia —

“What Charlie gave America is memory on canvas, an indelible impression of the way life really was during that short span of time in the 19th century before fences sprouted across the West,” says Nancy Plain, Spur Award-winning author of Sagebrush and Paintbrush: The Story of Charlie Russell, the Cowboy Artist.

Another noted artist of that period was Joseph Henry Sharp (1859-1953), who “stepped outside the bounds of many traditional western artists,” Peter H. Hassrick writes in The Life & Art of Joseph Henry Sharp. “…He painted scenes of women and men with equal fervor, never diminishing the former with sexist inferences, as Russell was wont to do in the 1890s.”

By the early 20th century, Will James (1892-1942) was “trying to invest art in a narrative, essentially painting and telling a story,” says Neal McEwen, education coordinator at the Phippen Museum in Prescott, Arizona. James was good at both, as his books, and the pen-and-ink and charcoal drawings often included in those books, attest. Russell and James greatly influenced George Phippen (1915-1966), who, as co-founder and first president of the Cowboy Artists of America, continues to influence artists today.

Tom Lea (1907-2001), the iconic Texas writer, illustrator, artist and muralist, was an exceptional chronicler of the Indian, Spanish, Mexican and Anglo cultures in early Texas, but his art, such as the 1940 mural Stampede in the main post office in Odessa, Texas, reveals his love of Italian Renaissance art.

While these artists helped influence how people looked at the West, history influenced artist Maynard Dixon (1875-1946).

— Courtesy Mark Sublette, Medicine Man Gallery, Tucson, Arizona —

“Even as mental snapshots of the West stimulate the budding painter’s imagination, the Old West begins to disappear,” says Mark Sublette, owner of Mark Sublette Medicine Man Gallery in Tucson, Arizona, and author of Maynard Dixon’s American West: Along the Distant Mesa. Sublette cites the 1889 Oklahoma Land Run, the Ghost Dance scare and the 1890 massacre of Lakota Indians at Wounded Knee by the 7th Cavalry. “These events, paramount in young Dixon’s consciousness, deepen his appreciation for Native cultures and sharpen his awareness of how quickly change is taking hold of the frontier. Like many others of his generation, Dixon hopes to paint the American Indians before their cultures perish. By the time he starts drawing in earnest, the buffalo have been hunted to the point of near-extinction; it is not unreasonable to fear the Native Americans they sustained are next.”

During the Golden Age of pulp magazines (1920s-1950s), Arthur Roy Mitchell (1889-1977) made a living painting covers and illustrations for magazines and novels before returning to his hometown of Trinidad, Colorado, to paint.

— Courtesy The Peterson Family Collection, Western Spirit: Scottdale’s Museum of the West, Scottsdale, Arizona —

“The covers…were meant to be eye-catching,” says Allyson Sheumaker, executive director of Trinidad’s A.R. Mitchell Museum of Western Art. “I believe the colors he chose in his illustrations reflected that. Most of his cover cowboys wore red shirts as an example. …His paintings reflect the light from a candle or oil lamp, the stance of a horse tied to a hitching post. It is my opinion that if the illustration was by Arthur R. Mitchell, it depicted the West he knew. The color of the cowboy’s shirt may be brighter, but the subject was true.”

The pulps all but disappeared by the 1960s, when other artists began looking at the West differently.

In the late 1960s, Fritz Scholder, a one-quarter Luseino Indian, began painting the “real Indian”—with an Indian drinking a Coors beer or a “Mad Indian” with the American flag behind him.

The latter part of the 20th century saw a new wave of Western art reinvigorated with Pop art interpretations by Andy Warhol (1928-1987). “When an artist of his significance and oeuvre weighs in on the American West, you have to take note of it,” says Seth Hopkins, executive director of the Booth Western Art Museum in Cartersville, Georgia.

— Courtesy The Bequest of Kenneth S. “Bud” Adams and Nancy Adams, Eiteljorg Museum, Indianapolis, Indiana —

Warhol’s contributions are on display in Andy Warhol and the West, co-developed by the Booth, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum and the Tacoma Art Museum. The exhibit runs at the Booth through December 31 before moving to Oklahoma City and Tacoma next year.

Warhol “wore cowboy boots almost every day,” Hopkins says. “He had a Roy Rogers alarm clock. What’s more Western than that?”

Where does Western art go from here?

Artist Thom Ross of Lamy, New Mexico, would like to see “artists with true imagination tackle the reasons why they care about Western art, and why we should care about it, too. If it matters, why does it matter? Challenge viewers. If your art isn’t doing that, then it’s not art—it’s a product.”

— Courtesy Whitney Western Art Museum, BBCW, Cody, Wyoming, Gift of William O. Sweet. 63.72.58 —

–—Courtesy A.R. Mitchell Museum, Trinidad, Colorado —

— Courtesy Permanent Art Collection, National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. 1972.028 —

— Courtesy Northeastern Nevada Museum, Winnemucca, Nevada —

— Courtesy the Whitney Museum Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Godwin Pelissero. 2.73 —

Johnny D. Boggs writes in his office, where an original painting of a Comanche Indian by Nocona Burgess and a Theresa Montoya original painting of St. Francis—patron of writers, editors and journalists—protect him.