When the beloved man’s funeral cortege passed the Adams Museum on March 3, 1943, a bell began tolling. It rang 77 times, matching the years of his life. Hymns played on carillons chimed from a distance as mourners grieved graveside at Mount Moriah Cemetery overlooking Deadwood, South Dakota. John Eli Perrett had died after a two-week illness, drawing to a close an era that marked the transition from pioneer prospecting exploits in Indian territory to America’s entry into WWII.

When the beloved man’s funeral cortege passed the Adams Museum on March 3, 1943, a bell began tolling. It rang 77 times, matching the years of his life. Hymns played on carillons chimed from a distance as mourners grieved graveside at Mount Moriah Cemetery overlooking Deadwood, South Dakota. John Eli Perrett had died after a two-week illness, drawing to a close an era that marked the transition from pioneer prospecting exploits in Indian territory to America’s entry into WWII.

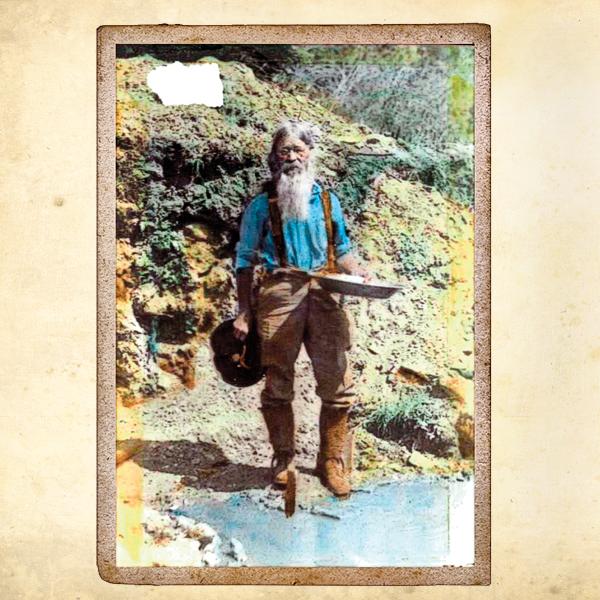

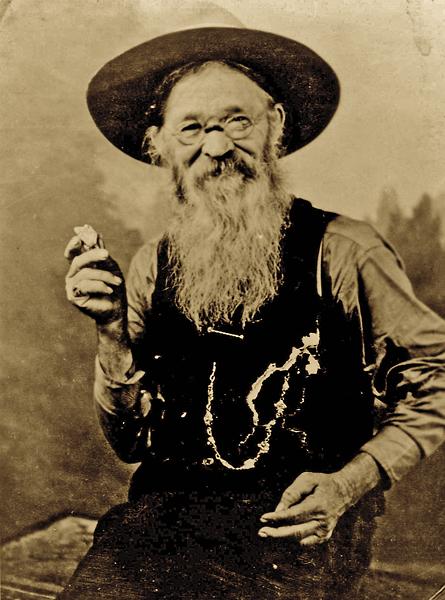

While few recognize his birth name, and some have spelled it as Johnnie or Perrott, many knew the man by the name he was given after bringing into town a large gold nugget he had found in a creek in the Black Hills. Reports list his date of birth as February 9, in either 1868 or 1866. Perrett arrived in Deadwood on a stagecoach in 1883 when he was 15 or 17 years old.

Despite news accounts reporting another Welsh village as Perrett’s birthplace, he was actually born in Abergavenny, a market town in Wales located about six miles from England’s border. Perrett traveled by ship with his father and sister from Wales to New York City, then by train to Sidney, Nebraska. The family rode by stagecoach to Central City in Dakota Territory, outside Deadwood, where his uncle operated a blacksmith shop.

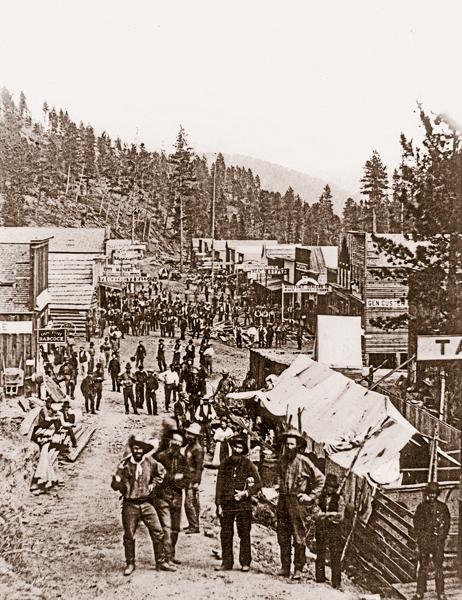

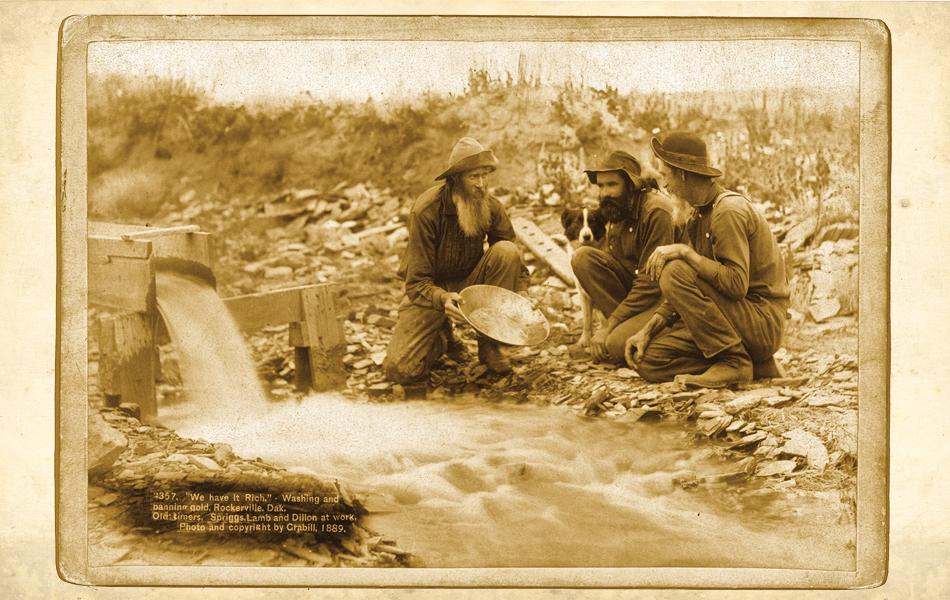

On May 27, 1929, five months before the crash of the stock market brought on the Great Depression, Perrett produced a 7.346-troy-ounce gold nugget that he said he had found on his claim in Potato Creek in Spearfish Canyon. His nugget created immediate and sensational news. The Black Hills that produced the gold chunk had been exploited for its mining wealth since 1875 when Deadwood was an illegal encroachment on Indian land, a settlement thrown up on a gulch along creeks that produced placer gold.

By 1876, thousands of miners had moved to the Black Hills, flaunting the Fort Laramie Treaty that ceded the land to the Lakota and other tribes forever. The government did not hold back the flood of immigrants. Rule was enforced by power; murderous thugs robbed miners of their claims and pokes.

By the time this young Welshman got to Deadwood in 1883, most of the miners had left. The “most disastrous flood” in the region’s history ravaged Deadwood that May, the creeks no longer gave up easy gold and mining companies were focusing on hard rock mining to extract ore from underground pits and tunnels.

“Potato Creek Johnny had a drinking problem, yet he had great animal magnetism. Bluebirds would land on his finger. He was a musician and looked the part of a miner with his long whiskers,” says Mary Kopco, executive director of Deadwood History, which operates the Adams Museum, the 1892 Adams House, Days of ’76 Museum and the Homestake Adams Research and Cultural Center.

Perrett’s fiddle playing and cranky nature ended up disrupting fellow employees of the Tinton tin mine. The mine put him to work in the pump house.

When the tin mine closed in January 1929, hard times befell the area. Perrett, who had married Molly Hamilton on March 13, 1907, was childless and divorced by 1928. Molly’s grounds for divorce stated her husband had kept a home like a junkyard, refused to allow his wife to clean it and had synchronized clocks that chimed to her distraction. Perrett, having lost his job at the tin mine, continued to prospect his claims outside Spearfish in Potato Creek.

Some suspected Perrett of breaking into a cottage owned by Capt. Edgar St. John, when he was hospitalized, to steal his gold. “Just as intriguing is the assertion by independent sources that to alter the gold dust’s appearances, thereby making it untraceable, Johnny went to George Veitl’s work shop behind Ayers Hardware Store in Deadwood, and had it melted together,” wrote Christopher Hills, in his book, Gold Pans and Broken Picks: The History of the Tinton Mining Region.

Hills reported that St. John recovered from his hospital stay and swore vengeance against Perrett. After a confrontation between the two on Deadwood’s Main Street, Perrett fled the scene. He emerged with his nugget, only after St. John had died.

Mystery always adds to the intrigue. No charges were filed against Perrett, and he was never arrested for theft of gold. Rumors persisted, but they never brought Perrett to a courtroom.

The news of Perrett’s find turned the little prospector into an overnight celebrity. He reveled in the limelight. With the U.S. Treasury setting the price of gold at $20.67 per ounce, the 7.346-troy-ounce nugget was worth about $152. An attorney offered Perrett $200 for it. W.E. Adams, the benefactor who created the history museum in Deadwood, raised the ante and offered Perrett $250, which he accepted.

The bewhiskered little man led Deadwood’s Days of ’76 parade that year. The city took him on tour to lure tourists to the area. He was pictured in Life Magazine and treated to meals by tourists who enjoyed his stories.

When something is touted as the largest, the biggest, the most of anything, that record will be challenged. The rival in this case was the “Doc” Wing nugget, reportedly found in 1879 from Bear Creek in the Black Hills. In 1931, the Black Hills Engineer acknowledged Potato Creek Johnny’s nugget, but also reported that the 1879 nugget was valued at $465. Calculating the price of gold at $20.67, that nugget would have had to weigh 22.5 troy ounces. Yet the existence of the Wing nugget remains unconfirmed. To this day, no other nugget from the Black Hills has been proven to be larger than Potato Creek Johnny’s.

Experts have confirmed the authenticity of Johnny’s nugget. James O. Aplan, of Antique Appraisal Association of America, issued a report on June 29, 2011, stating: “It is my opinion that the Potato Creek Johnny nugget is the single, most valuable artifact of Black Hills history in existence…. Based upon my over 60 years of buying, selling and evaluating historical Americana, I would value the true, original, famous Potato Creek Johnny nugget

at $500,000.”

“Gold experts have found it to show quartz crystal in it. You can’t manufacture that. The longer we go on with expert opinion, the more certain Johnny found it in situ like this,” Kopco says.

“In the Black Hills, you just don’t find nuggets this size,” she adds. The closest anyone has come was when “two modern-day prospectors found what is now called the Icebox nugget in 2010.”

Prospectors Charlie Ward and Byron Janis formed their Icebox Mining Company to prospect the creeks and alluvial deposits throughout the Black Hills. On July 6, 2010, they discovered a 5.27-troy-ounce nugget, with a gold content that measures 3.96 troy ounces. Their discovery stirred up interest just like Potato Creek Johnny had enjoyed.

Chris Johnson who, with his son, Trevor, owns the Clock Shop in Rapid City, says the Icebox nugget they purchased has been appraised for more than $100,000. “I doubt any larger nuggets will be found. This is the first [of its kind] found in about a hundred years,” Chris says.

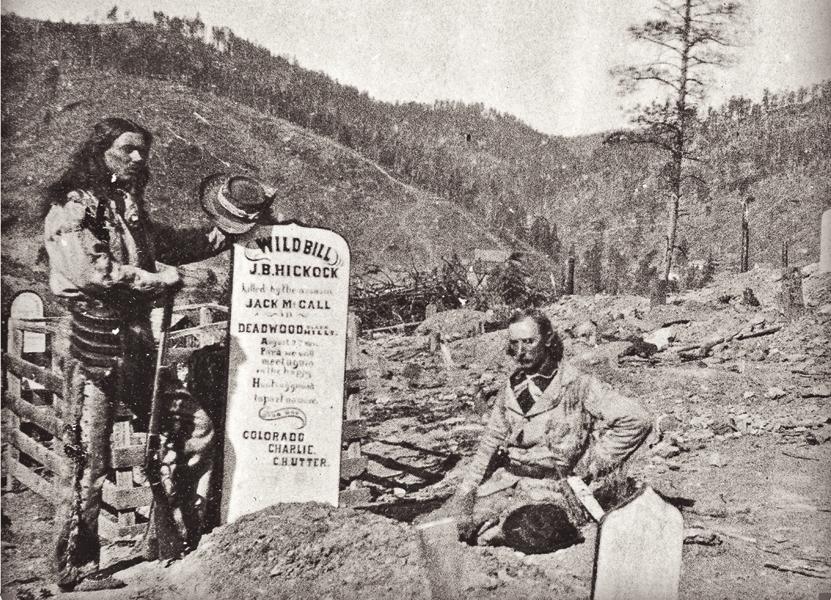

The largest nugget, though, remains the one found by Perrett, who was buried alongside Deadwood’s other legends, Wild Bill Hickok and Calamity Jane. When gold prices teetered at almost $2,000 an ounce during recent uncertain economic times, the lure of prospecting brought new interest to the Black Hills, a place where, as Kopco says, “Our history is stranger than fiction.”

John Christopher Fine has worked extensively in South Dakota where he helps support a conservancy for wild Spanish mustangs. He is a marine biologist and expert in marine and maritime affairs. He is the author of 25 books.

Photo Gallery

–Courtesy Deadwood Public Library –

– Courtesy South Dakota State Historical Society –

– By Myriam Moran –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– All images Courtesy Deadwood History, Adams Museum Collection, Deadwood, SD, unless otherwise noted –