I’ve waited until May to come back, figuring that a late fall or early winter trip would be too depressing. Besides, driving across rural southeastern Colorado in November can be deadly.

I’ve waited until May to come back, figuring that a late fall or early winter trip would be too depressing. Besides, driving across rural southeastern Colorado in November can be deadly.

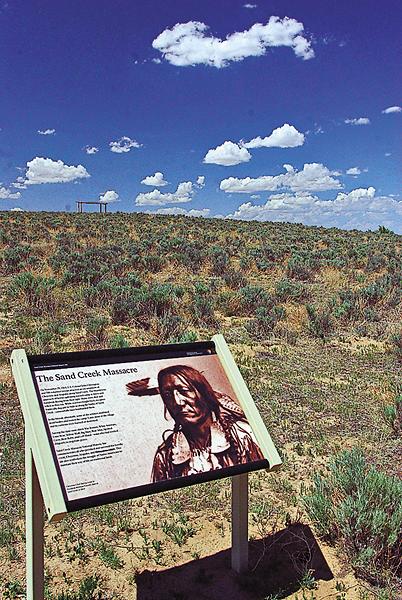

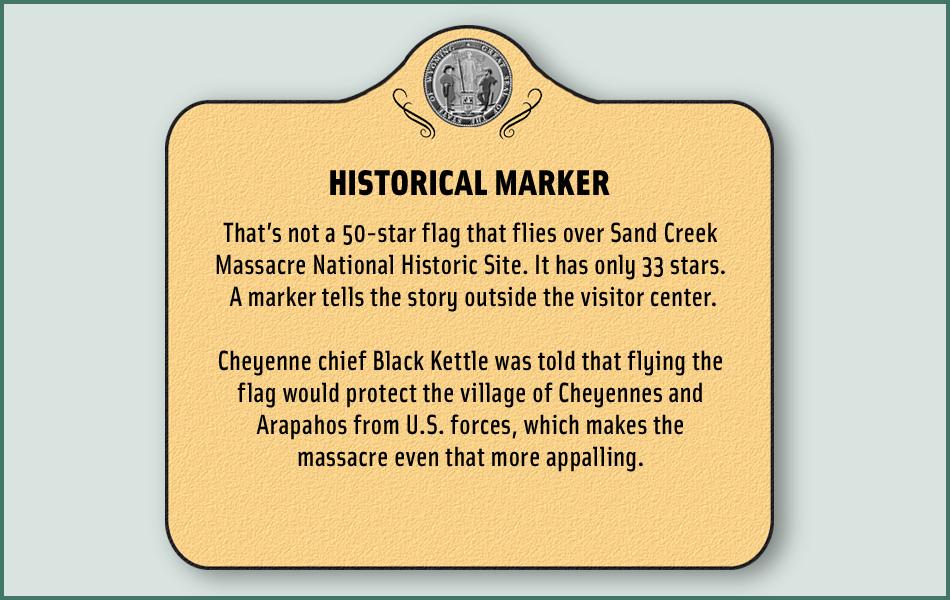

The last time I came here, in the late 1980s—years before Sand Creek was dedicated as a National Historic Site in 2007—tears streamed down my face as I looked over the plains where once an American flag flew over a peaceful village of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians.

Hey, I get emotional at the 9/11 Memorial in New York City and at the Vietnam “Wall” in Washington, D.C., but those are personal. Friends of friends died during the terrorist attacks of 2001, and a first cousin’s name is on that wall. But no historical site affects me like Sand Creek.

It’s 90 degrees as I turn off the unpaved county road and head toward park headquarters, but already I feel chilled.

“This is not a feel-good park,” Shawn Gillette, Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site’s chief of interpretation, tells me. “A group of Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians who wanted peace and got assurances of peace came here and were attacked by the United States Army.”

On November 29, 1864, a cavalry force led by Col. John Chivington attacked a Cheyenne and Arapaho encampment. Cheyenne peace chief Black Kettle raised a U.S. flag and a white flag, but many soldiers, in particular the 3rd Colorado, paid no attention.

White Antelope, almost 80 years old, and Standing in the Water, probably in his 60s, walked out to meet the soldiers, but were shot down. They “were the first two Cheyennes killed,” says independent historical investigator Jeff C. Campbell, who lives in nearby Eads.

What followed was horrible.

Independent historian Louis Kraft, who is writing Sand Creek and the Tragic End of a Lifeway for the University of Oklahoma Press, reminds me:

“Volunteer troops used small children for target practice, an unborn child was cut from its dead mother’s body and scalped, three women and five children prisoners were executed by a lieutenant as their guards backed away in horror and while they begged for their lives. Many of the bodies gave up between five, seven and sometimes eight scalps. Penises, vaginas and breasts were cut from the dead and displayed as ornaments and trophies.”

A century and a half later, the Cheyenne and Arapaho peoples aren’t calling this an anniversary, but a healing. How should we remember this?

“For exactly what it was,” Kraft says, “an outrage and a devastating wound that still burns within the soul of today’s Cheyennes and Arapahos.”

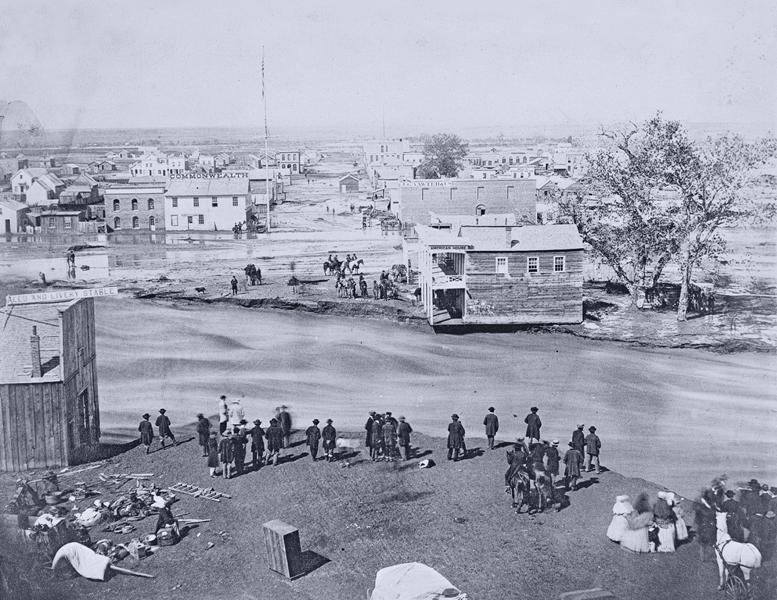

If you want proof of how deep these wounds cut, head to Denver, where I started this road trip.

On June 11, 1864, Nathan Hungate’s family was killed, and “Indians” were blamed. “Neither the Cheyennes, Arapahos or any other tribe has been proved to be responsible for the murders of the Hungate family,” Campbell says. “Even the coroner’s inquest couldn’t name suspects.”

Yet the remains of those victims were displayed in Denver, white settlers became outraged, and territorial Governor John Evans told “friendly Indians” to go to “places of safety,” including Fort Lyon. He also authorized citizens to “kill and destroy … hostile Indians.” On August 11, the U.S. War Department authorized a 100-day volunteer cavalry and put Chivington, a hero of the 1862 Civil War battle of Glorieta Pass in New Mexico, incommand of the military district.

Sand Creek Pilgrimage Begins in Denver

I’m inside the History Colorado Center, a fabulous state-of-the-art museum downtown. When I first visited the museum shortly after it opened in April 2012, it presented an exhibit on Sand Creek. But no more.

In the summer of 2013, the museum closed the exhibit after receiving complaints from Cheyenne and Arapaho Indians. The tribes had not been consulted before the exhibit went up, and objected to a “collision of cultures” explanation of what happened.

“We continue the consultation process with the tribes and, while this takes place, the exhibit remains closed,” outgoing public relations director Rebecca Laurie says.

Back in September 1864, Indian leaders, including Black Kettle, met with Evans and Chivington near Denver. The Indians followed instructions and headed to Fort Lyon, where, after more discussions, they moved to Sand Creek for forage and game.

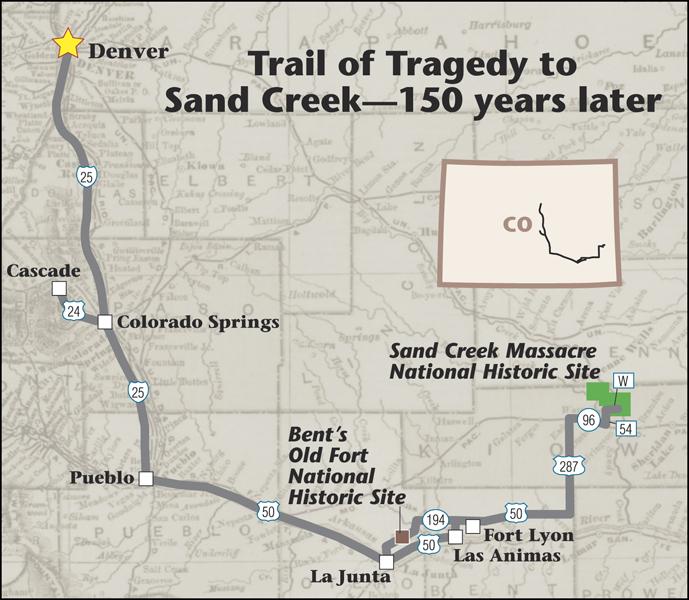

I left Denver for Cascade, just outside of Colorado Springs. I’m staying at Cascade Escapes’ Ramona Cottage, which happens to be walking distance to The Wines of Colorado, where I pair the state’s best wines with the restaurant’s outstanding dishes.

Besides, I remember that line in Kraft’s one-man play Cheyenne Blood, about Ned Wynkoop, one of the strongest white voices condemning Sand Creek:

“Indeed, I have been wrongly accused of raising a glass of fine juices to these lips far too often. That’s why some people call me Wine-koop.”

Okay. I needed to find some comedy on this trip. But there’s another reason to visit Colorado Springs and vicinity. In 1858, gold was discovered in Colorado, setting off the Pikes Peak rush.

That history is well documented at two Colorado Springs museums: the Colorado Springs Pioneers Museum and the Ghost Town Museum, both fun for children and adults.

The gold rush brought thousands of white settlers to Colorado, and led to the Treaty of Fort Wise (which would become Fort Lyon) in 1860. The agreement greatly reduced the Cheyenne-Arapaho hunting grounds established in 1851. But many Indians, possibly unaware of the new treaty, kept hunting on their old grounds.

It’s time to head away from the mountains and toward Sand Creek.

The Road to Sand Creek

In Las Animas, the John W. Rawlings Heritage Center and Museum offers a nice look at regional history, while Fort Lyon, which closed in 1867 and was a minimum security prison until 2011, is on the National Register of Historic Places, including a national cemetery established in 1907.

In November, the 3rd Colorado—by then being derisively referred to as the “Bloodless Third” for its lack of combat—and the 1st Colorado headed for Fort Lyon, soon joined by other companies. Chivington and his staff left Denver on November 20.

He arrived at Fort Lyon on November 28, and that night rode north with roughly 675 men and four 12-inch mountain howitzers.

Chivington, an ordained (but inactive) Methodist minister, reportedly said: “I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heaven to kill Indians. Kill and scalp all, big and little; nits make lice.”

Did he really say that?

“Most likely,” Campbell says. “General [William] Harney was credited with that quote [after the battle at Ash Hollow, Nebraska, in 1855], and Chivington often thought he had ‘eclipsed Harney.’ However, in one form or fashion that quote goes back to Roman times, ad infinitum.”Make sure you visit Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site, a reconstructed 1840s adobe post and excellent living history museum near La Junta.

William Bent, who married a Cheyenne woman, helped establish the post along the Arkansas River. Three of his mixed-blood sons would be at Sand Creek on that ugly morning.

“A unique way to compare Denver attitudes versus Arkansas Valley attitudes helps explain a lot,” Campbell says. “Along the Arkansas Valley, people got along, both Indian and white, but in Denver ‘the Indian had to go.’”

My Solemn Return to the Massacre Site

So here I am at Sand Creek, once again overlooking the campsite—off-limits to visitors, out of respect for the dead.

As more research is uncovered, the number killed increases. “It’s about 200,” Gillette says, “and it’s probably going to grow.”

Not every soldier, however, took part in the massacre, which lasted between six and eight hours. Captain Silas Soule and Lieutenant Joseph Cramer ordered their soldiers to stand down. Soule reportedly even placed his men between the attackers and retreating Indians.

Soule wrote Wynkoop: “I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized.”

While Chivington and his men would be feted as heroes upon their return to Denver, in Washington and elsewhere, the massacre would be condemned.

Chivington, however, went to his grave in 1894 denying any culpability. “I stand by Sand Creek,” he often said.

Soule would later be killed in Denver. Some argue his death was a conspiracy for his testimony against Chivington. Others say that, as provost marshal, he unfortunately lost a gunfight.

“The descendants of the Cheyennes and Arapahos who were here 150 years were largely responsible for establishing this park,” Gillette tells me. “And they wanted it to be for all Americans, not just their own people.”

These wounds, however, still hurt.

“War doesn’t give soldiers the right to murder, rape and butcher,” Kraft says. “Not yesterday, not today, and not ever.”

***SIDE ROADS***

PLACES TO VISIT

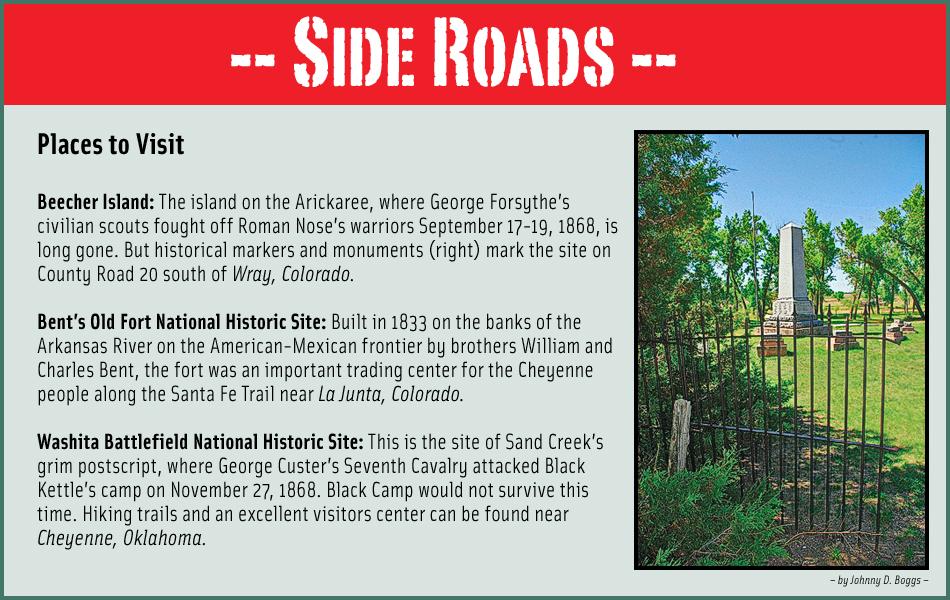

Beecher Island: The island on the Arickaree, where George Forsythe’s civilian scouts fought off Roman Nose’s warriors September 17-19, 1868, is long gone. But historical markers and monuments (above) mark the site on County Road 20 south of Wray, Colorado.

Bent’s Old Fort National Historic Site: Built in 1833 on the banks of the Arkansas River on the American-Mexican frontier by brothers William and Charles Bent, the fort was an important trading center for the Cheyenne people along the Santa Fe Trail near La Junta, Colorado.

Washita Battlefield National Historic Site: This is the site of Sand Creek’s grim postscript, where George Custer’s Seventh Cavalry attacked Black Kettle’s camp on November 27, 1868. Black Camp would not survive this time. Hiking trails and an excellent visitors center can be found near Cheyenne, Oklahoma.

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

Good Grub: Fruition (Denver); The Wines of Colorado (Cascade); Shamrock Brewing Co. (Pueblo); K&M Ranch House Restaurant (Eads).

Lodging: The Oxford Hotel (Denver); Ramona Cottage at Cascade Escape (Cascade); Bent’s Fort Inn (Las Animas); Third Street Nest Bed & Breakfast (Lamar).

GOOD BOOKS/ FILM & TV

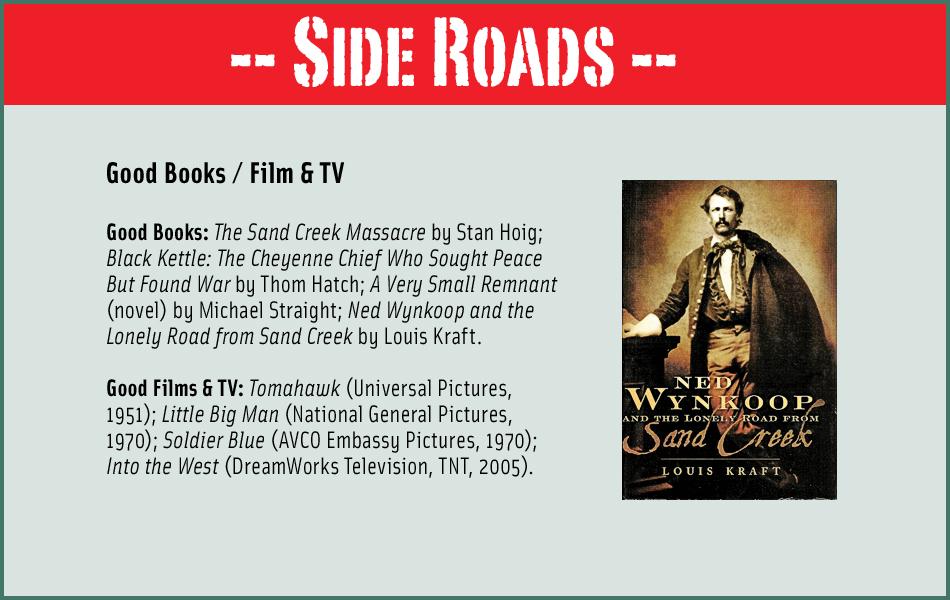

Good Books: The Sand Creek Massacre by Stan Hoig; Black Kettle: The Cheyenne Chief Who Sought Peace But Found War by Thom Hatch; A Very Small Remnant (novel) by Michael Straight; Ned Wynkoop and the Lonely Road from Sand Creek by Louis Kraft.

Good Films & TV: Tomahawk (Universal Pictures, 1951); Little Big Man (National General Pictures, 1970); Soldier Blue (AVCO Embassy Pictures, 1970); Into the West (DreamWorks Television, TNT, 2005).

Johnny D. Boggs recommends checking out SandCreekSite.com, and the Sand Creek Massacre National Historic Site webpage at NPS.gov, before traveling to the massacre site.

Photo Gallery

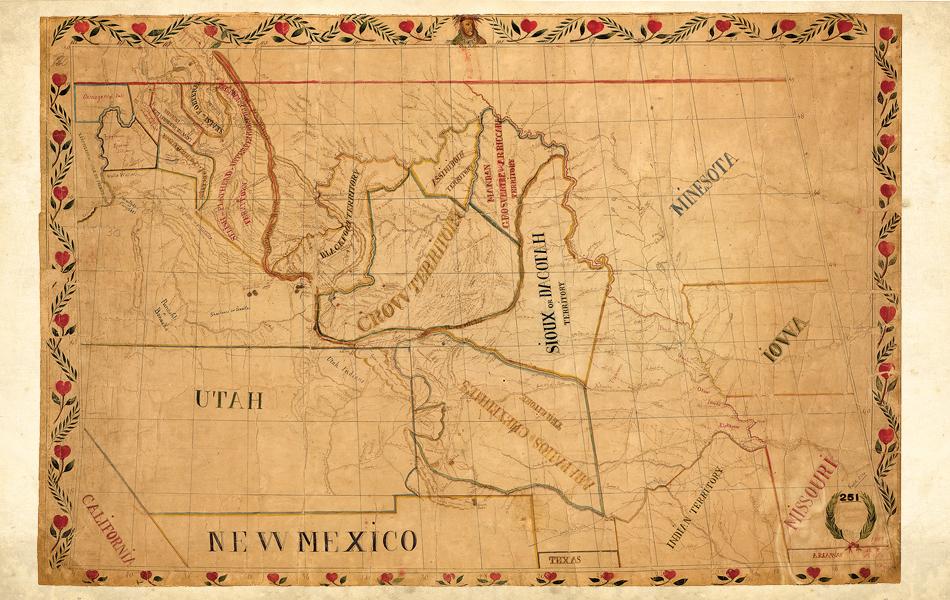

– True West Archives –

– Photo Courtesy National Park Service –

– Photo Courtesy National Park Service –

– by Mathew B. Brady/Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Colorado Historical Society –

– Photo by Johnny D. Boggs –

– Photo by Johnny D. Boggs –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Library of Congress –