Buffalo Bill Cody rode many a famous mile across the West, but did he actually ride for the legendary Pony Express?

Near the Pony Express exhibit at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper, Wyoming, the docent was asked, “Did Buffalo Bill actually ride the Pony Express?” The docent replied, “Well, Bill said he did.”

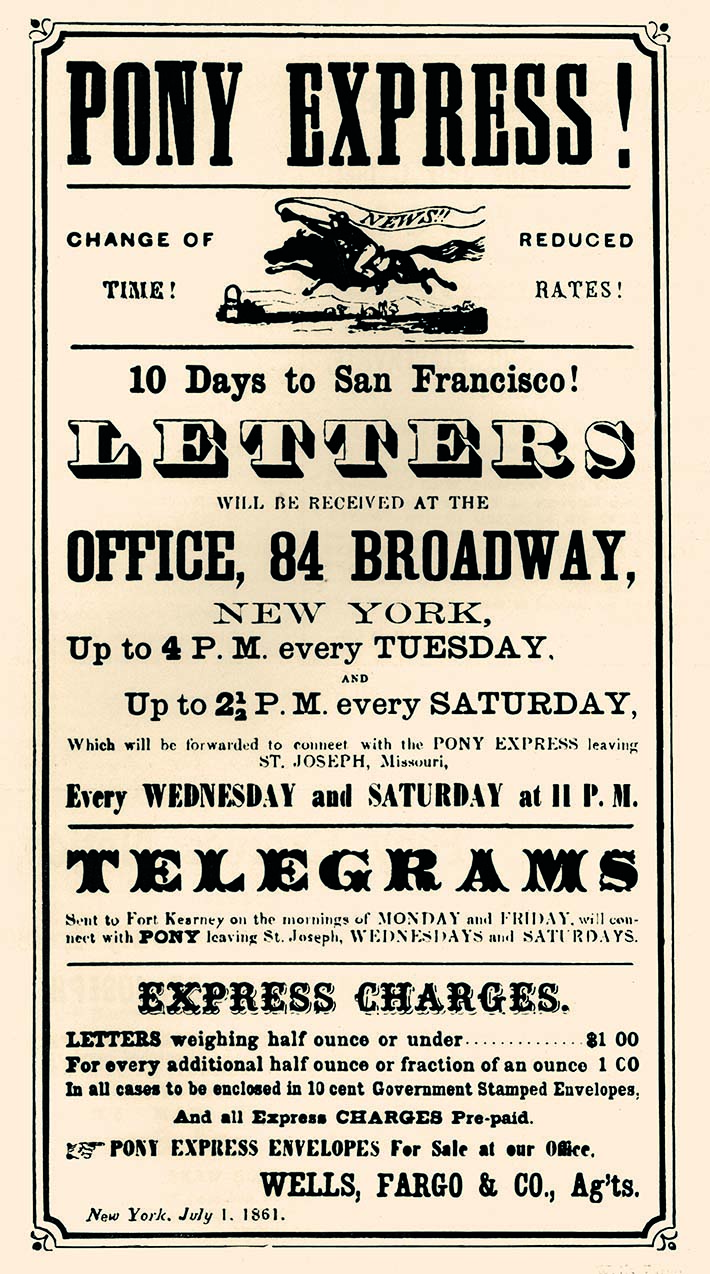

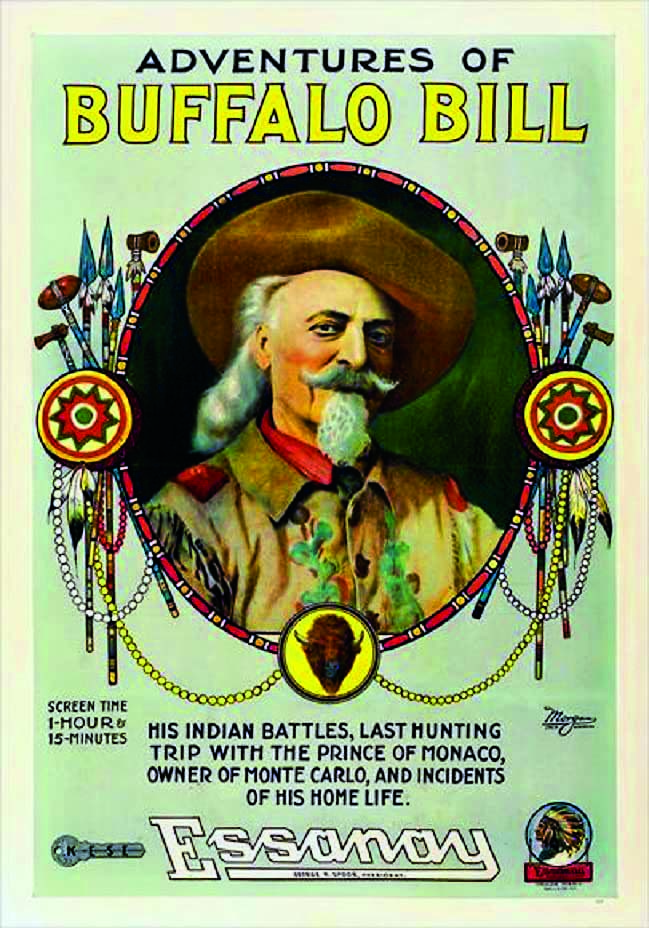

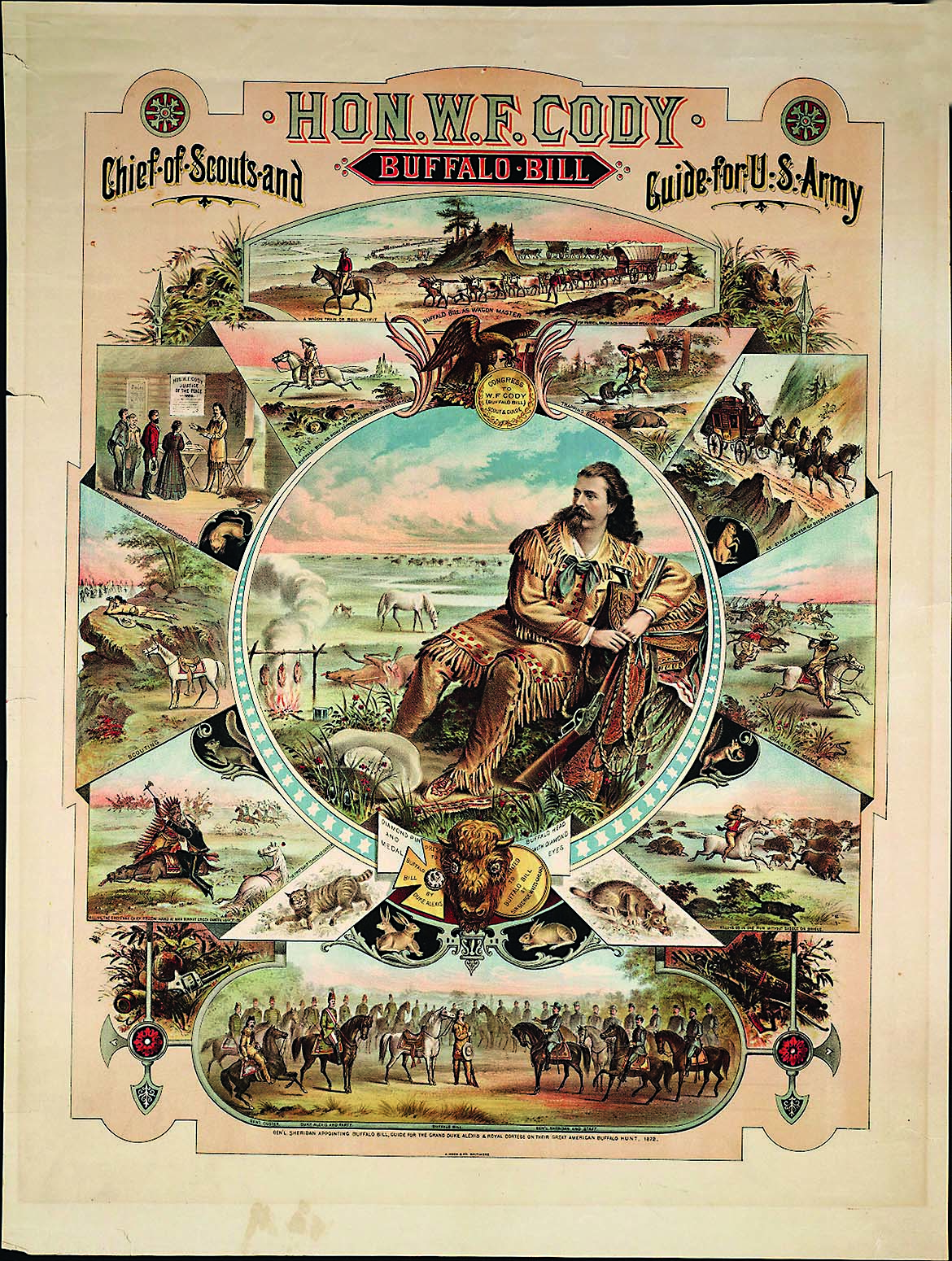

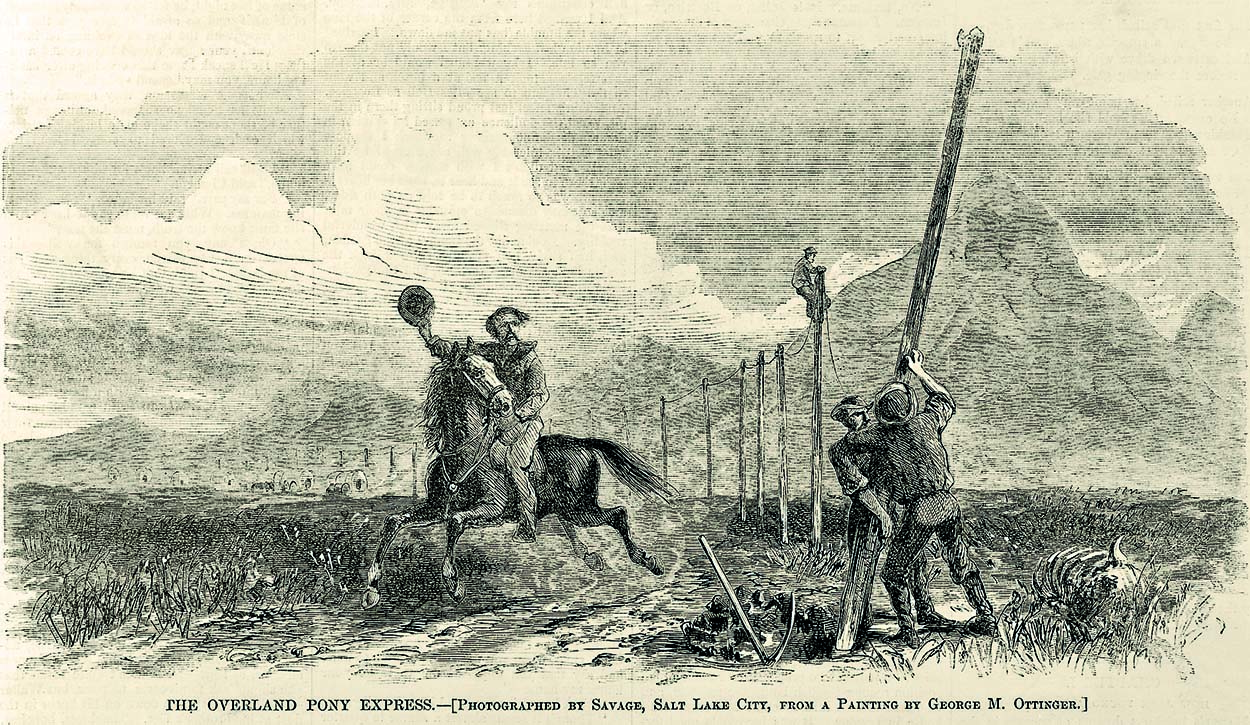

Much has been written about William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody and the Pony Express. Much of it he wrote himself. Certainly Cody and the Pony Express are inexorably joined. The Pony Express, which lasted a mere 18 months, would be a small paragraph in the voluminous annals of the history of the American West had not W. F. Cody made it a featured act of his long running Wild West show.

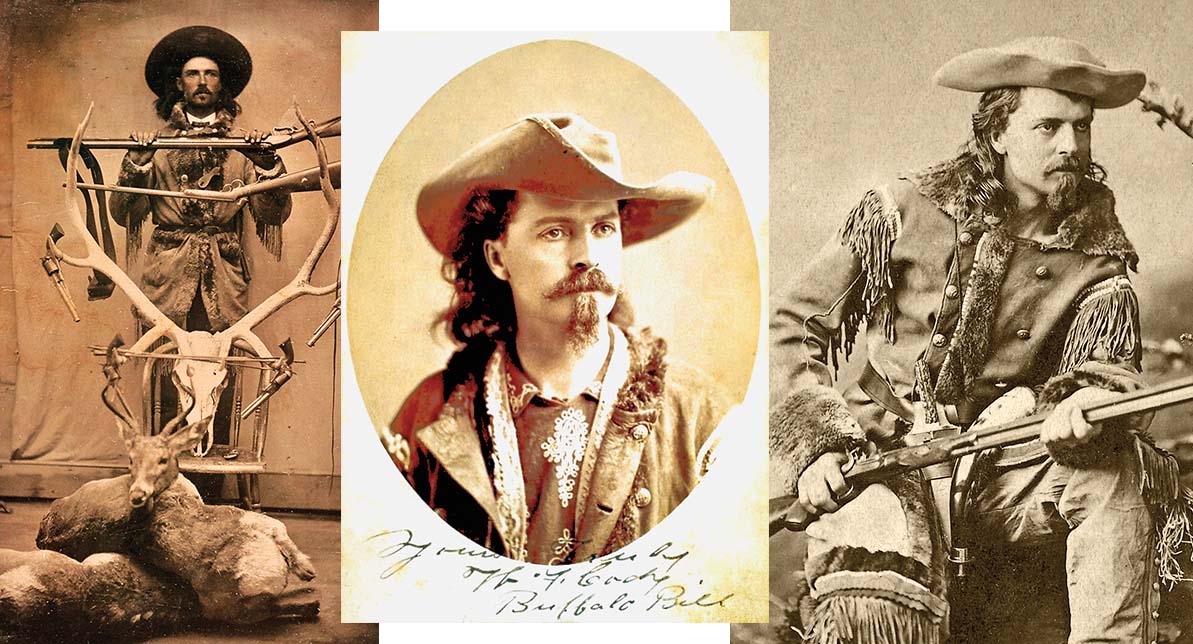

In his autobiography (Buffalo Bill’s Life Story written in 1878 and published in 1879), Bill recounts that he was “now in my fifteenth year” when the Pony Express began operations in April 1860. Although he was only 14 years of age, Bill used this literary device to add an apparent year to his age. Pony Express regulations called for riders 18 years or older, although it is known that a few riders younger than 18 were hired. While it’s possible that Bill could have been hired at age 14, it is highly improbable.

– Courtesy BBCW, P.6.648.05 –

Prior to operating the Pony Express, William Russell, Alexander Majors and later William Waddell, whose firm was headquartered in Leavenworth, Kansas, had government contracts to distribute supplies to the U.S. Army on the Western frontier. Bill’s widowed mother, needing money to hold onto their farm outside of Leavenworth, Kansas, allowed the extremely young Bill Cody to drive cavayard (extra cattle) with wagon freight trains three years in succession. He worked his way up to relief bullwhacker, relief driver and utility man; but he always returned home, tended to the farm and attended school over the winter. Bill writes that in one year his wages were paid by Majors directly to Bill’s mother each month while he was away. Therein lies Bill’s first connection to the Pony Express. Russell and the Codys were personally acquainted. Bill even referred to Russell as “Uncle Aleck.”

– True West Archives –

In late 1859, the 13-year-old Cody headed to the Rocky Mountains to prospect for gold. With no experience to rely on, he, like so many others, was easily discouraged. He claims to have built a raft as a way to get home to Leavenworth. In Cody’s writing of the story, the raft conveniently capsized on the South Platte River near Julesburg, Colorado Territory, the only home station on the Pony Express route in what would become the state of Colorado. It was there that he claimed he rode for the notorious station master Jack Slade.

In his autobiographical recounting of his Pony Express adventures, Bill mentions that the messages they carried “were written on the thinnest paper to be found.” (Correct) “These were carried in a waterproof pouch, slung under our arms.” (Wrong) Obviously, Bill didn’t know at the time that Pony Express messages were kept in four locked compartments called cantinas, which were attached to the four corners of what was called a mochila. The mochila could be flung from one saddle over the next saddle as the horses were exchanged. A Pony Express rider would absolutely know of the mochila. A few years after he wrote his autobiography, Bill must have authenticated the equipment for the Pony Express act in his Wild West show.

In writing of the dangers of riding through hostile Indian country, Bill reported that “Road agents [robbers} were another menace, and often proved as deadly as the Indians.” The Pony Express, it was known, carried neither precious metals or currency, and no recorded losses to road agents are to be found.

Pony Express rider Jack Keetley is credited with a ride of 340 miles in 31 hours without stopping to eat or sleep. “Pony Bob” Haslam holds the record for the longest run, a 360-mile ride through Paiute territory in 40 hours. In his autobiography, Cody claims the record. His longest ride, he wrote, was 320 miles in just 21 hours and 40 minutes. Is that even possible?

Cody’s account of his Pony Express experience is full of adventures, almost too many to believe. He writes that he was attacked by 15 Indians on one occasion. Not likely. Then, about a six-week suspension of Pony Express service, Cody wrote that he volunteered, along with Wild Bill Hickock, to join a party of 40 men in pursuit of Express horses stolen by Indians. Hickock, Cody wrote, planned the successful dawn attack near Crazy Woman Fork, Dakota Territory (present-day Wyoming), recapturing hundreds of horses, hundreds of miles north of the station. As soon as they returned the horses, Cody records that service resumed.

Unfortunately, the only documented suspension of Pony Express service occurred in May 1860 during the Pyramid Lake War in northwestern Nevada. Paiute warriors destroyed numerous Express stations and killed 16 employees, including one rider. The company actually suspended delivery for three weeks (not six), and the suspension of service occurred much farther west than Bill reported he rode.

As for James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickock, Cody wrote, “We rode the Pony Express together.” They did not. While Hickock was employed at the Rock Creek station, he had a famous shootout with the McCanless gang (later changed to McCandless). However, Hickock did not ride for the Pony Express—and never said he did!

By the time Alexander Majors got around to writing his own memoirs in 1893, he was old, ill and penniless. Cody found him in Colorado and helped him by taking Majors on as part of Cody’s Wild West show. For a time, Majors lived at Cody’s Scouts’ Rest Ranch outside North Platte, Nebraska.

Alexander Majors’ memoirs were ghostwritten, or at least heavily edited, by Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, a fabled dime novelist and hack. Majors dedicated what amounts to a hodgepodge of recollections to Cody. Cody wrote the preface and paid Rand McNally to print it. After the book was published, Majors complained that Ingraham had taken liberties with his story. Is it at all surprising that Majors’ account of Cody’s Pony Express experience is an almost verbatim account of Cody’s own account of one of his rides?

Frank Christianson wrote in the introduction of his 2011 edited version of Cody’s autobiography: “Cody operates securely within the American autobiographical tradition by fashioning an archetype out of his individual and composite experience. Consequently, some events in the [his] narrative may never have happened, others likely happened to someone else, while still others that occurred are either exaggerated or understated… A close examination has shown, for instance, that Cody’s claim that he worked for the Pony Express is questionable.”

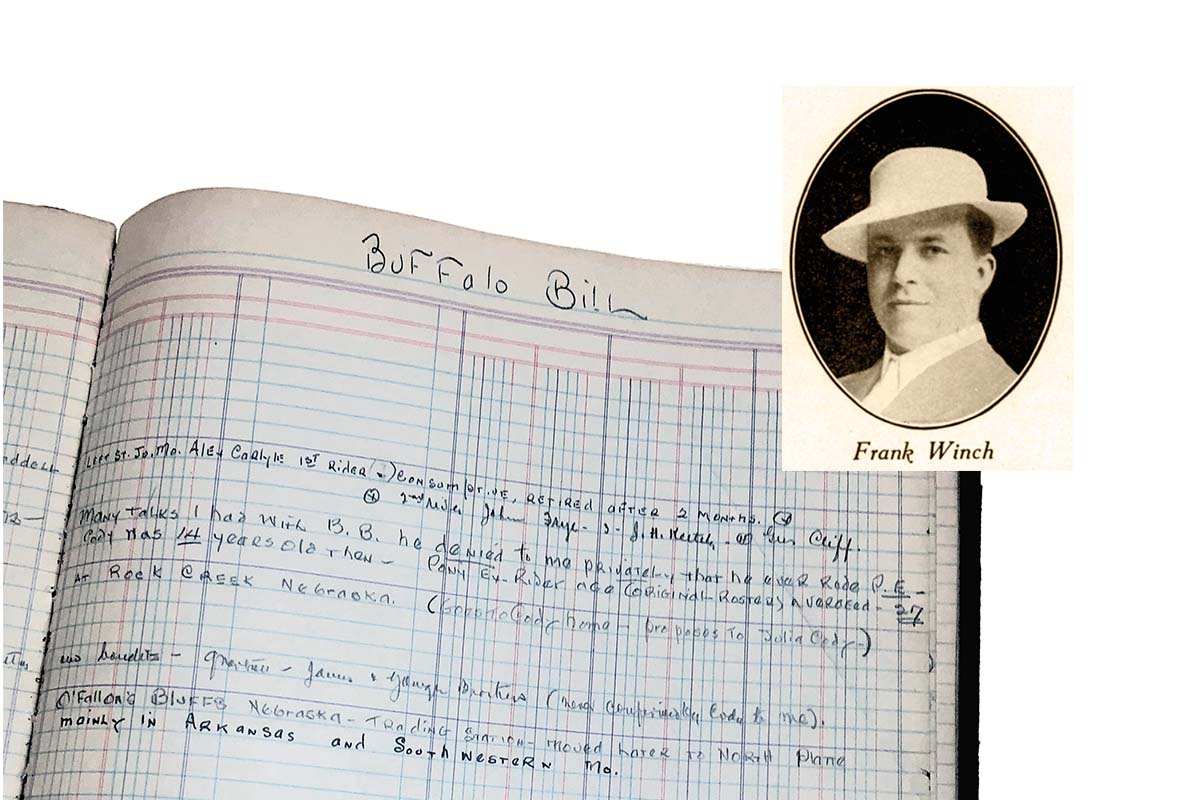

The now-retired but longtime curator of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave in Golden, Colorado, Steve Friesen debated with me on the merits of “Did he or didn’t he?” Friesen had me nearly convinced that Bill had actually ridden the Pony Express. I arose to leave, turned to the door, and Friesen said, “By the way, Frank Winch, who knew Cody for many years, wrote a timeline of Cody’s life. When it came to the Pony Express, Winch wrote, ‘He didn’t.’”

Winch’s extensive chronology of Cody’s life, written shortly after Cody’s death, can be found in the archives of the Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave. Winch knew Cody for many years, as he was a public relations man for the Wild West show and wrote a biography for Cody and Pawnee Bill which was sold at the combined shows in 1911 and 1912.

What Frank Winch wrote in the April 1860 entry of the chronology is the most credible evidence for the answer to our question: “It is claimed,” wrote Winch, “that Cody was a P.E. Rider. Many talks I had with B.B. He denied to me privately that he ever rode P.E.” (Underlines attributed to Winch.)

– Photo of Frank Winch Journal Courtesy Buffalo Bill Museum and Grave/Frank Winch Photo Courtesy Buffalo Bill Center of the West –

Convincing evidence exists that Majors did give Cody, a boy in need at age 11, a job riding a mule or a pony delivering messages for his freight-hauling firm between Leavenworth and Atchison, Kansas. And, an even younger Cody did accompany Russell’s wagon teams on three different occasions. However, much like P.T. Barnum and the dime novelists of his day, Cody was never shy of embellishing his past.

After all is researched and written, perhaps the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, reports it best. At the exhibit that features the Pony Express it is written:

– Courtesy Beinecke Library, Yale University –

Cody’s exploits became legendary. But was he really a Pony Express rider? Evidence is ambiguous, and scholars disagree. However, two points are clear. Cody was a messenger for Russell, Waddell and Majors, and Cody believed he had ridden for the Pony Express. Perhaps he viewed them as one in the same.

The only evidence that Cody rode the Express was Cody’s own words and Alexander Majors’ autobiography, which was ghostwritten by a writer of questionable authenticity and paid for by Cody himself. To say that William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody did not ride the Pony Express is not revisionist history. It is truthful, accurate history.

– True West Archives –

If this issue were to be settled in a court of law, the evidence against Cody riding the Pony Express would be overwhelming. It is past time that historians of the American West disregard Cody’s claim.

A marketing executive and copywriter, J. David Holt is a first-time contributor to True West, but passionate about this topic. He has previously written for Western Horseman, Reader’s Digest and Kansas City Star Magazine.