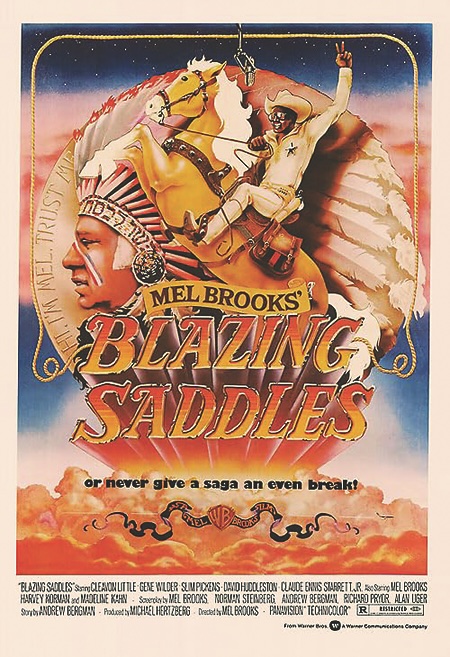

A half-century after Andrew Bergman penned Blazing Saddles, the epic comic Western is still a cultural tour de force.

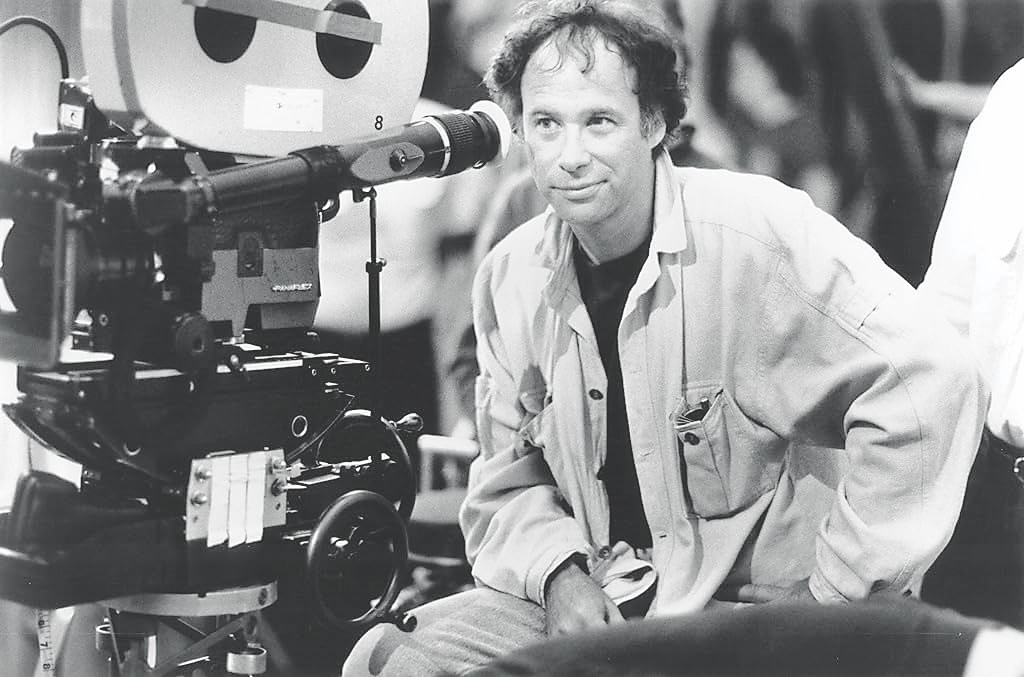

Sure, Andrew Bergman has written Broadway musicals, written and directed wonderful comedies like The In-Laws, So Fine, The Freshman and Honeymoon in Vegas. He’s also written the Hollywood and LeVine detective novels, and the history of Depression-era American film, We’re in the Money about which he says, “It’s the only book I’ve written that’s still in print.” But all of that was superfluous; he’d already achieved screen immortality by writing the novella Tex X, which, in the hands of Mel Brooks, became Blazing Saddles.

Bergman had become an academic out of necessity. “I got a PhD because in that period of time, it was get a PhD or go to Vietnam,” he says. “But I really loved the research, and writing [We’re in the Money] was fascinating and very instructive.”

I asked him if he’d always intended to make films.

Bergman: I was always a writer. When I was a little kid, I was writing stories. My father had been a newspaperman and had aspirations to be in the movie business. Both my parents were German refugees, and he had worked for Universal Studios in Berlin back in the ’30s when he was a kid. He’d always wanted to be in the movie business, but he couldn’t. So this was my revenge.

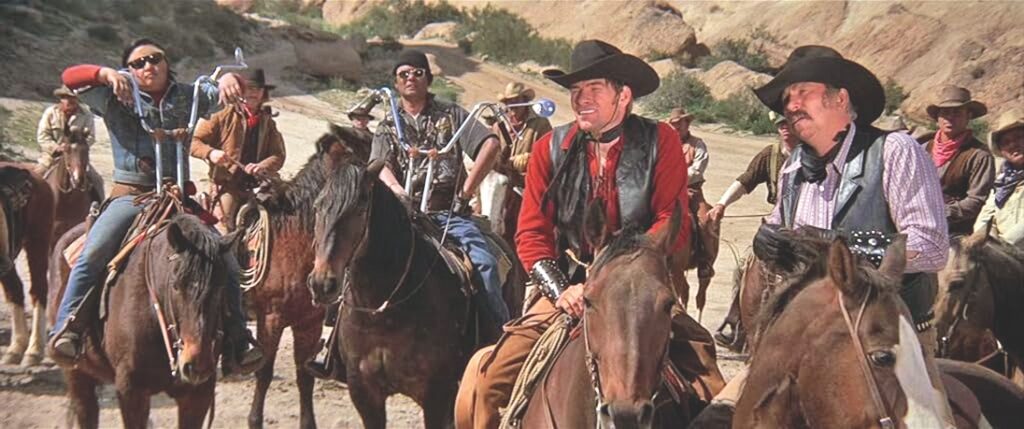

Parke: In 1974, the top Westerns were Billy Two Hats, Zandy’s Bride and The Spikes Gang. How dead were Westerns when you set out to do this?

Bergman: They were pretty dead, but I think the movie was so funny, and it drew upon the fact that Westerns were in a state of, sort of paralysis. It’s what got people turned on about Westerns again: “Oh, yeah. I remember Westerns!” It sort of rekindled that love of Westerns. You know when you’re a kid, you go to the movies, and you sit there in the 30th row, talking at the screen and yelling back at it? This was like a movie about people talking back to the screen.

Parke: Had you written many screenplays before Tex X?

Bergman: I didn’t even know how to read screenplays. But I just had an idea, a vision really, of a town waiting for a sheriff to show up. And he’s Black; and not only is he Black, he’s like H. Rap Brown coming to be sheriff. It was my only high-concept idea. I wrote a 90-page story, which I sold to Warners, then wrote a first draft. And they hired Alan Arkin to direct it, and James Earl Jones was gonna play the sheriff. But that didn’t work, ’cause James Earl Jones is not a comic actor. So the studio said, “What do you think about Mel Brooks?” I said, “I love Mel Brooks!” Mel loved the concept, and he wanted to write in the manner he had worked on Your Show of Shows, with a group. I was 26.

Parke: What was that experience like?

Bergman: Fantastic. First it was Mel and me, Norman Steinberg, Alan Uger. And Mel said, “We can’t have four Jews writing a movie about a Black sheriff. We gotta have a Black writer in it.” We got Richie Pryor. It was madness and hilarious. Uger dropped out, and then Richie went back to being Richie, and there was just Norman and Mel and me, and we wrote, like, another 15 drafts. It was a fantastic experience. I had never written anything, and it was an education in writing and certainly in comedy between Mel and Richie, who were two absolute genius comic brains and fabulous fellows. As funny as the movie was, that room was funnier.

Parke: Are you a fan of Westerns?

Bergman: I love Westerns. In fact, the thing that impelled me…was when Wild Bunch came out, summer of ’69, it just obliterated me. I just fell in love with Westerns all over again.

Parke: Any other particular Westerns you liked?

Bergman: High Noon was a great Western. I grew up watching Hopalong Cassidy every afternoon. I mean, it was in my bones.

Parke: I always wondered why it was, “You’d do it for Randolph Scott,” and not Joel McCrea.

Bergman: One thing about comedy writing is consonants are much funnier than vowels. Joel McCrea doesn’t give you anything, and Scott gives you those hard Ts at the end.

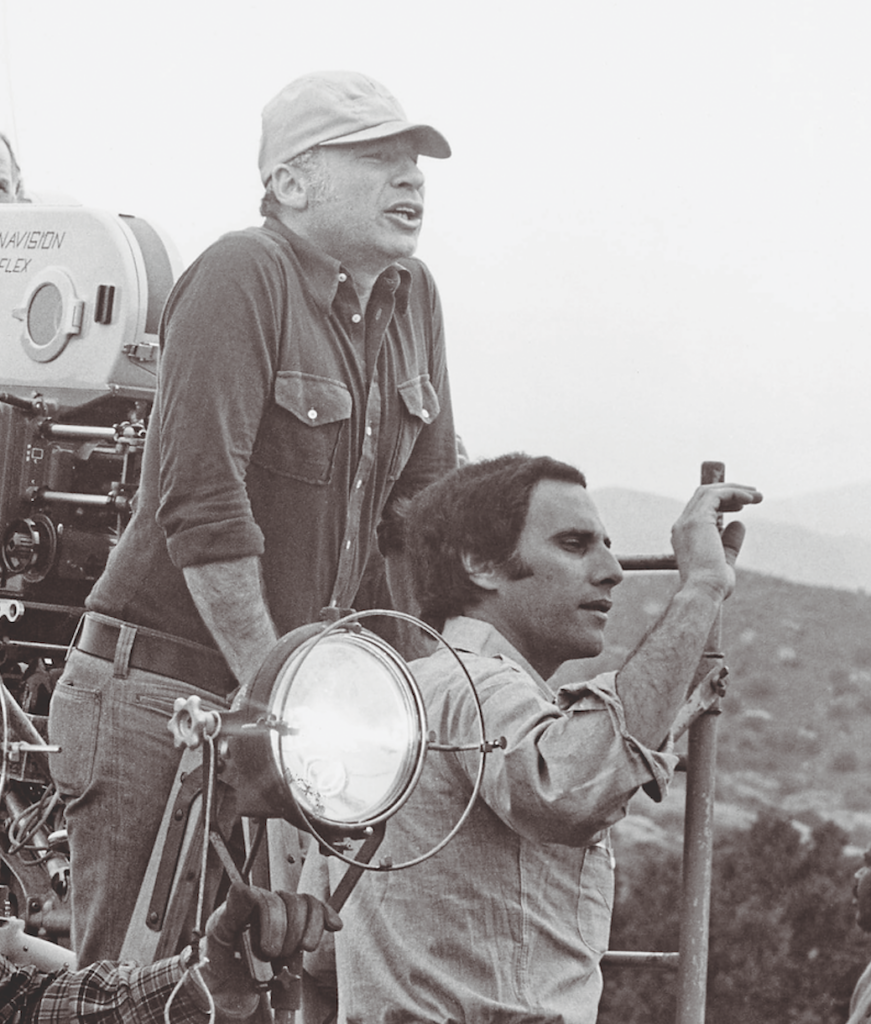

Parke: Were you on set a lot?

Bergman: I was not, because the Writers Guild strike began the day we started shooting, so I never went on the set because of the picket lines. It was a pity. And Mel thought [the filming] was going horribly. He called to say, like, “Our dream is dead. This thing is gonna stink!” And then lo and behold, this creature was born.

Parke: Like Mel Brooks, you went from writing movies to writing and directing. Were there any lessons or things you observed from Mel Brooks that you took with you?

Bergman: Not the directing, because I wasn’t on the set. But the writing, for sure. The comic rhythm is very much like musical rhythm, and Mel’s very musical. And the way lines scan, in terms of comedy, is everything.

Parke: Did any cast members make a particular impression on you?

Bergman: Ironically, when I first wrote the story, the first person I showed the story to was Cleavon Little, because I’d seen him in a show on off-Broadway called Scuba Duba. I said, this guy’s perfect. So it was sort of serendipity who ended up playing the part. I was involved in the casting, sort of helped put the cast together with Harvey, Madeline Kahn and Slim Pickens, who I loved always.

Hedley Lamarr, are timeless and forever funny homages to the Western horse-operas of the 1920s and 1930s.

Parke: How about Gene Willder?

Bergman: Gene was a last-minute choice. Our original guy was Dan Dailey, and he couldn’t do it because his eyesight was failing. And then Gig Young, who couldn’t do it. So we were stuck. We had to get somebody, and Mel just begged Gene Wilder to do it, and Gene said, “I’ll do it if you do this other movie that I wrote,” which was Young Frankenstein. That’s how that happened. And he was wonderful. We envisioned somebody older, but it just turns out if the part’s right, you know it.

Parke: Was the ending, when the characters essentially crash through the fourth wall, in your original story?

Bergman: My original story was quite traditional, although there was an interracial romance, but in this movie, the love interest is like a Nazi. So it’s sort of a way to have an interracial romance and nobody cares about it, nobody takes it seriously, which is quite brilliant. But, no, the breaking out, we had finished it, and Mel said, there’s something missing. He said, “We need a bigger ending.” And that’s when we came up with this insane Warner Brothers kind of riot that breaks out at the end of the movie.

Parke: How did Blazing Saddles affect your career?

Bergman: Oh, my God. How about everything? It was sort of like winning the lottery. It was amazing and totally unexpected that it would be such a hit, you know? And the studio didn’t think anybody’d go see it. But it just hit a nerve, and it was really funny. And it holds up; it’s as funny today as it was then.

Parke: It’s often said that you couldn’t make Blazing Saddles today. Is that true?

Bergman: Oh, absolutely. What hasn’t changed? In what way does this world resemble the world of 1974? First of all, in just the money terms, the movie would be unaffordable today. With the locations, and a million extras. That movie cost under two and a half million dollars to make. Today, it would cost about a hundred, which means you’d have to cast an all-star cast, and you just lose everything that made it Blazing Saddles. And I don’t even know what politically correct means. It just means not funny. I mean, you just can’t deal in reality, or heighten reality. It’s like you’re running for office. Every piece of art is running for office, so make nice to this group and that group, and this group, and it’s…it’s not art anymore. It’s some other thing, a political feel-good thing.

of the German Dancer and the Grouchy Moviegoer.

Blu-Ray REVIEW

DAYS OF HEAVEN

(Criterion; Blu-Ray $39.95, 4K + Blu-Ray $49.95) Only silent-movie filmmakers have told a story as visually as writer/director Terrence Malick did in Days of Heaven (1978), and cinematographer Nestor Almendros earned his Oscar not only for the ephemeral beauty of the prairie, but for the filth of a 1916 Chicago slum and the worry-worn faces of the desperate and hopeless. Impoverished steel-worker Richard Gere assaults his supervisor, then flees with kid-sister Linda Manz, and his love, Brooke Adams. Harvesting wheat, Adams catches the eye of wealthy farmer Sam Shepard, who believes she is Gere’s sister. It’s wrong…but it’s the chance of a lifetime, a short one for Shepard, who is dying. Western villain Robert Wilke is heartbreaking

as Shepard’s foreman and proxy father. The deceptively simply score is by Ennio Morricone. Manz’s narration is unforgettable.

Henry C. Parke, Western Film and TV Editor for True West, is a screenwriter, and blogs for the INSP Channel, and at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com. A book based on his True West columns, The Greatest Westerns Ever Made, was published by TwoDot in February.