When did the Army invert its chevrons and why was that done?

Bob Rooks (Fort Worth, Texas)

Chevrons are the stripes on a uniform arm that denote rank or experience. From 1820 to 1903, the insignia was worn with the point down. From 1903 to 1905, there was some confusion, and rank could be worn with the point either up or down. On November 30, 1905, the War Department determined that the points of the chevrons would be worn points upward.

The reason given was that stripes pointing up denoted success in war, a sign of strength and winning. By that reasoning, points facing downward was a sign of having lost, or of weakness. Some of America’s toughest allies, the Canadians, British and Australians, wear their chevrons pointing down. They can provide some heated debate on that one.

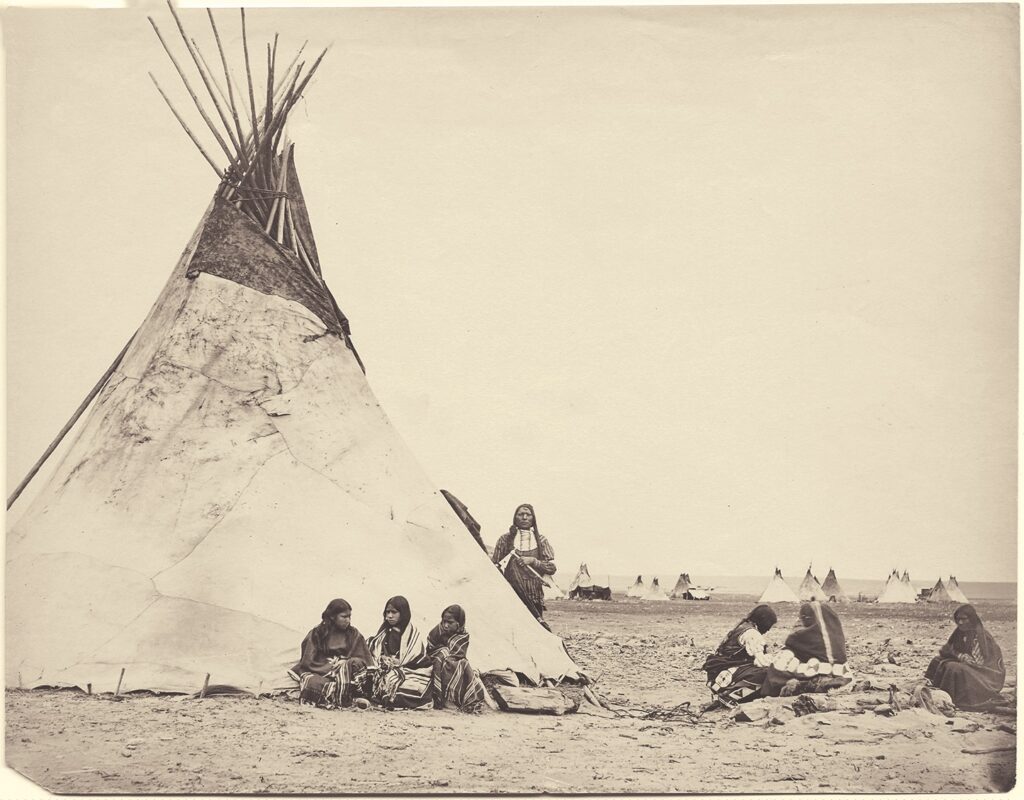

Many Southern Plains tribes (Comanche, Kiowa, Southern Cheyenne) lived in areas with few trees. How did they get poles for their tepees?

Kevin Henderson (Round Rock, Texas)

All these tribes ranged hundreds if not thousands of miles from their usual stomping grounds, the Llano Estacado. The lodgepole pines are native to the Rocky Mountains, growing in middle to high elevations in dry, cold forests. They are conveniently close to where those tribes spent part of the year. Spruce trees also made good lodgepoles.

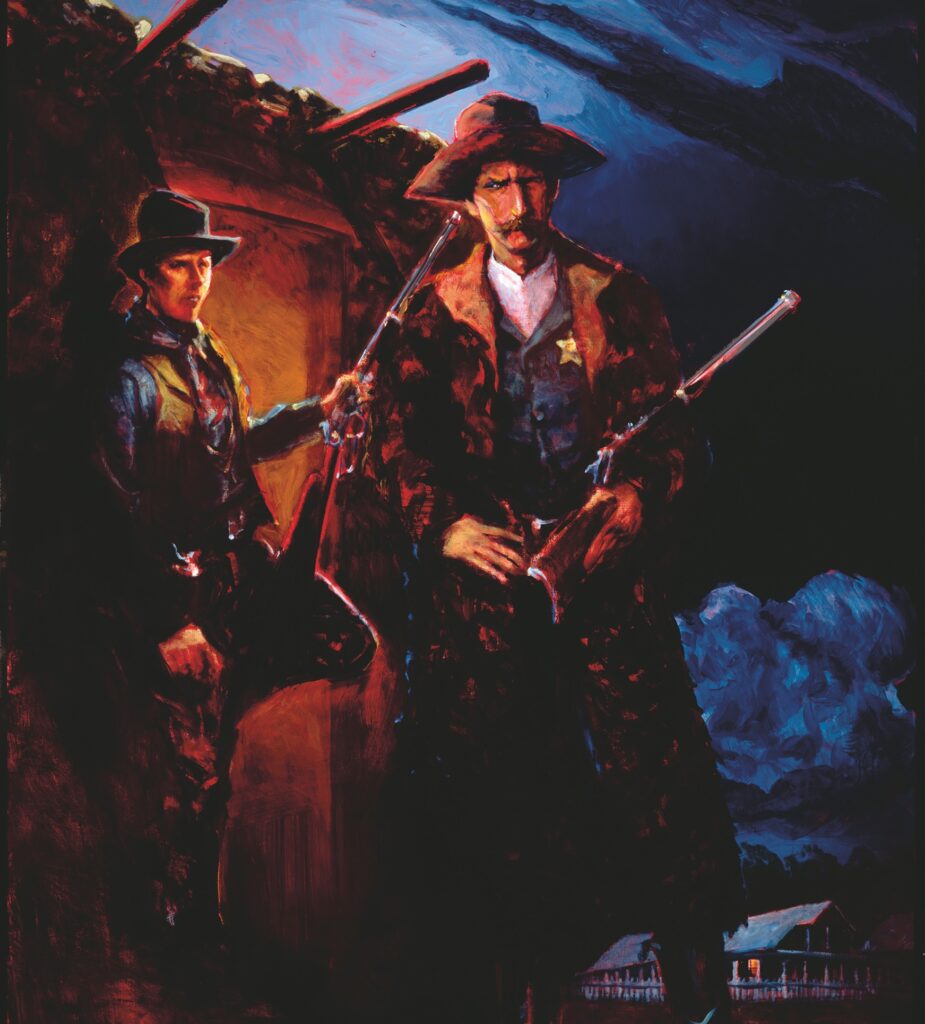

Were Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid friends?

Charlie Fowler (Dallas, Texas)

It’s likely they knew each other, but they weren’t close friends.

When was the last Indian war attack in the U.S.?

Harry Delger (Charleston, South Carolina)

During the late 1800s and the early 1900s, the Yaqui people were fighting the government of Mexico, hoping to establish an independent homeland in Sonora. Yaqui warriors joined in the rebellion when the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910, but by 1916 Mexican generals were claiming Yaqui land as their own, which led to renewed conflict between Yaqui and Mexican military forces. On January 8, 1918, at Bear Valley in southern Arizona, The Battle of Bear Valley was fought between the Yaqui Indians and the U.S. 10th Cavalry troops.

The Yaqui had been illegally purchasing weapons in the U.S. Believing the Buffalo Soldiers were Mexican troops, they opened fire on them. After a firefight, the troopers overtook a group of 10 Indians who were covering for the escape of the rest of the band into Mexico and took them captive. One officer later wrote of the engagement that it “was a courageous stand by a brave group of Indians; and the Cavalrymen treated them with the respect due to fighting men.” All 10 Yaqui were captured, including the chief, who had been badly wounded and died the next day.

The surviving prisoners were held at Arivaca while the Army awaited orders from Washington. Eventually, they were sent, in chains, to Tucson for trial in federal court, where they were charged with illegal exporting of arms without a license. The adults were sentenced to 30 days, a much preferable outcome than deportation to Mexico, where they would have been executed.

Was the Henry repeating rifle ever used as a buffalo gun?

Joe Manriquez (Whittier, California)

The Henry was seldom used as a buffalo gun. It was designed for human targets. According to Andrew Bresnan of the National Henry Rifle Company, the Henry was not a powerful round, but it held 16 quick shots with which to repel a sudden Indian attack. The cartridge, with its 200-grain bullet and 26 grains of black powder, is a marginal hunting round. The New Haven Arms Company, however, made claims to the contrary, saying it was lethal on buffalo and bear. Despite its popularity, only some 14,000 were ever produced.