They said Cattle Kate was a dirty rustler and a filthy whore.

They said Cattle Kate was a dirty rustler and a filthy whore.

They cried out, “rangeland justice,” when she became the only woman ever lynched in the nation as a cattle rustler.

They called her killing “justified” when six prominent cattlemen strung her up with her secret husband on a hot July Saturday in 1889 in Wyoming Territory.

They said, “She had to be killed for the good of the country.”

Even now, in the 125th anniversary year of her death, plenty still say history got it right and that her lynching was good riddance to bad rubbish.

But as titillating as that legend is, it doesn’t hold a candle to the truth.

Because history was dead wrong about the woman labeled “Cattle Kate.”

Digging for the Truth

The real woman the cattlemen lynched that day wasn’t a rustler. She wasn’t a whore. And she’d never been called Cattle Kate until she was dead and her culprits needed an excuse.

Her real name was Ellen “Ella” Watson. She had just turned 29. She was one of the few female homesteaders in all of Wyoming Territory and a wannabe American citizen. She was raising a boy, and she was cooking dinners at her secret husband’s roadhouse for 50 cents a plate. Her big sin was her homestead claim, with its precious water rights, in the way of her powerful cattleman neighbor, A.J. Bothwell.

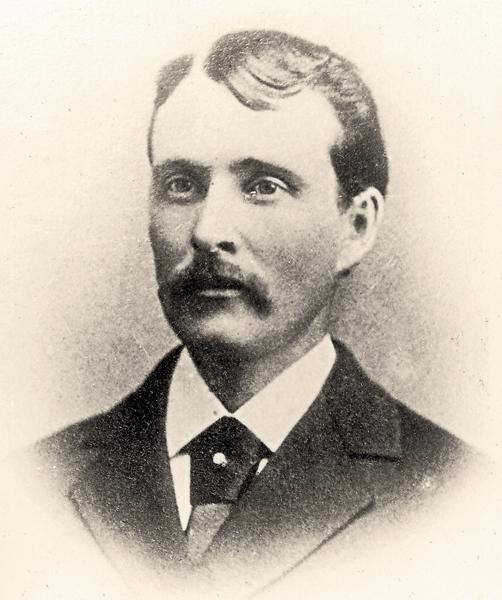

Don’t forget her husband, 38-year-old James Averell, whom the Cheyenne daily newspapers portrayed to the world as her pimp and a murdering cur.

In reality, Averell was about the most successful “settler” in the Sweetwater Valley between Rawlins and Casper. He had been appointed postmaster by President Grover Cleveland, notary public by Wyoming Gov. Thomas Moonlight and had just been named a justice of the peace by the Carbon County Board of Commissioners. Twelve days before the lynching, Averell was one of the election judges when his roadhouse hosted the election of delegates to the Wyoming Constitutional Convention—the same roadhouse the Cheyenne dailies would pretend was a “hog ranch” full of prostitutes.

Averell was also fearless in his “letters to the editor,” which exposed the land grabbers and the misdeeds of the cattlemen who were trying to keep out homesteaders. His latest attack had revealed that Bothwell’s “Town of Bothwell” was nothing but a land scam.

But darn, if history isn’t stubborn about clinging to myths and fabrications that fit the favored plot line. For a long time, the favored plot line in this tale was that cattlemen were being ruined by ruthless rustlers, and that “Cattle Kate” and Averell were the leaders of the pack. Twenty-five years after the lynching, Dr. Charles Penrose, in The Rustler Business, went so far as to declare, “She had to be killed for the good of the country.”

Not until 87 years had passed since the lynching did anyone question history’s take on “Cattle Kate.” The first book to say, “Whoa,” was Dorothy Gray’s Women of the West, in 1976. She quotes an unnamed source calling Watson’s hanging the “most revolting crime in the entire annals of the West,” which is saying something for a history filled with revolting crimes.

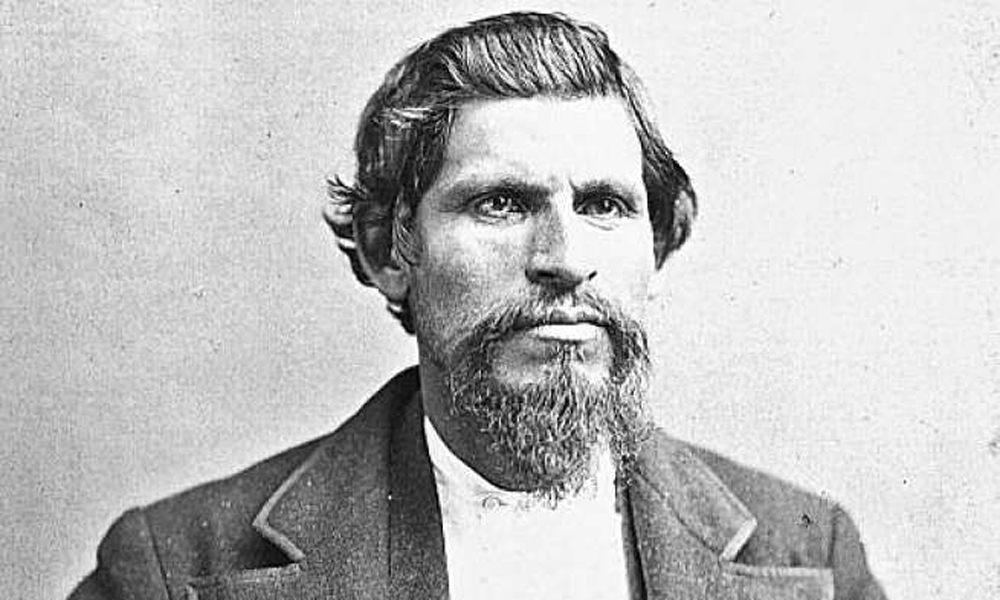

But what set history on its ear was George W. Hufsmith’s 1993 book, The Wyoming Lynching of Cattle Kate, 1889. “When I first began probing into the so-called ‘Cattle Kate’ affair, I had no idea that the whole story was pure fabrication,” he wrote.

“This story is so controversial,” he added, “that for over 100 years, it was a mistake to even ask what happened that hot July afternoon in 1889 when a gracious young woman and an innocent homesteader were hanged from a pine tree in the Sweetwater Valley.”

After more than two decades of study, Hufsmith concluded: “Not one shred of substantive evidence exists to show that those two settlers were anything but hard-working homesteaders, trying to eke out a living from a primitive and difficult environment.”

The same assessment came from Daniel Y. Meschter, who spent 25 years researching his 1996 book, Sweetwater Sunset.

In 2003, Lori Van Pelt wrote an excellent piece questioning the legend—her essay didn’t exonerate Watson, but it raised important questions. In 2005, I wrote a profile of Watson for True West’s Women of the West series under the headline: “So-Called Cattle Kate Rises from Rubbish: Evidence points toward Ella Watson’s innocence.”

I have spent the last five years investigating this Western legend and writing a historical novel in her voice. What I find remarkable about this story is not just her disgusting murder and the lies told to excuse it, but the extraordinary woman she ends up being for real.

The Real Ella Watson

The eldest of 10 surviving children, Watson was born on July 2, 1860, in Ontario, Canada, and moved with her family to a homestead near Lebanon, Kansas, in 1877. Bucking the norm of the day, Watson shocked Lebanon when she divorced her first husband, farm laborer William Pickell, on Valentine’s Day, 1884—and then demanded her maiden name back. An abusive drunk, he had often beat her with a horsewhip.

She fearlessly went West on her own during 1883 to 1886, ignoring the fact that most women went with their fathers, brothers or husbands. She ultimately chose Wyoming to settle in because women already had the vote and the territory still offered land to claim under the Homestead Acts.

As tongues wagged, an unmarried 25-year-old Watson joined 34-year-old James Averell at a roadhouse in early 1886. Unknown to anyone, they secretly married a couple months later, miles away in another county. Historians agree the couple had come up with the ruse so each could file multiple claims as “head of household.” As a married woman, Watson couldn’t own land in her own name.

On August 30, 1886, Watson filed a “squatter’s claim” on 160 acres adjacent to Averell’s homestead claim on Horse Creek. She went to court to fight off a neighbor’s bogus “timber claim” on the land—land without trees. In 1888, in the territorial capital, Cheyenne, she would file the formal paperwork for Claim 2003.

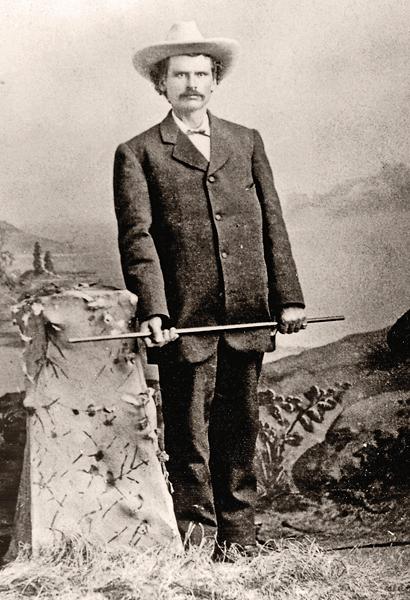

All that time, she and Averell fought constantly with their powerful neighbor, Bothwell, who declared Watson’s claim was on his pasture land and blocked his right to water in Horse Creek. Insult became injury when Bothwell was forced to buy an easement from the couple to get access to the water—a trench 15 feet wide and 3,300 feet long.

In the meantime, on May 25, 1887, Watson filed for citizenship, taking home the test she would have to pass in five years to become an American citizen.

In October 1888, she bought 28 head of cattle, stated two men who were with her that day. That December, she tried to get a legal brand through the official brand committee of the Wyoming Stock Growers Association, but the committee wouldn’t give her one—just as its members repeatedly refused a brand to Averell for any future cows he would own.

Watson outsmarted the cattlemen by buying a brand from neighbor John Crowder, who was moving on. She officially registered her LU brand with the Carbon County Brand Commission on March 20, 1889.

She became like a stepmother to 11-year-old Gene, believed to be John Crowder’s son. She also took in 14-year-old John DeCorey, who became a general handyman around her homestead. Her “family” included Averell’s 20-year-old nephew from Wisconsin, Ralph Cole, and neighbor Frank Buchanan, who would try to stop the double hanging led by Bothwell and John Durbin, two of the most prominent cattlemen in the territory. By the time the case came before the grand jury, none of her “family” appeared to identify the six men who had hanged the couple: Cole had died under mysterious circumstances; Buchanan and Gene disappeared; and DeCorey fled to Colorado for safety. All the lynchers walked free.

Watson’s name and honor were defended with a shocking lawsuit filed by the executor of her estate, Carbon County Coroner George Durant. While the murder charges were still hanging over their heads, Bothwell and Durbin were sued for $1,100. Durant’s suit accused them of stealing Watson’s cows and rebranding them as their own on the day they lynched her. The cattlemen’s attorney continuously delayed court hearings, until the case was finally dismissed—51 months after Watson was buried.

“The Homesteaders’ Heroine, Cattle Kate, and the Land Grabbers in the West.” That was the headline suggested by former Wyoming Sen. Joseph C. O’Mahoney, in a 1960s letter to a writer investigating the case.

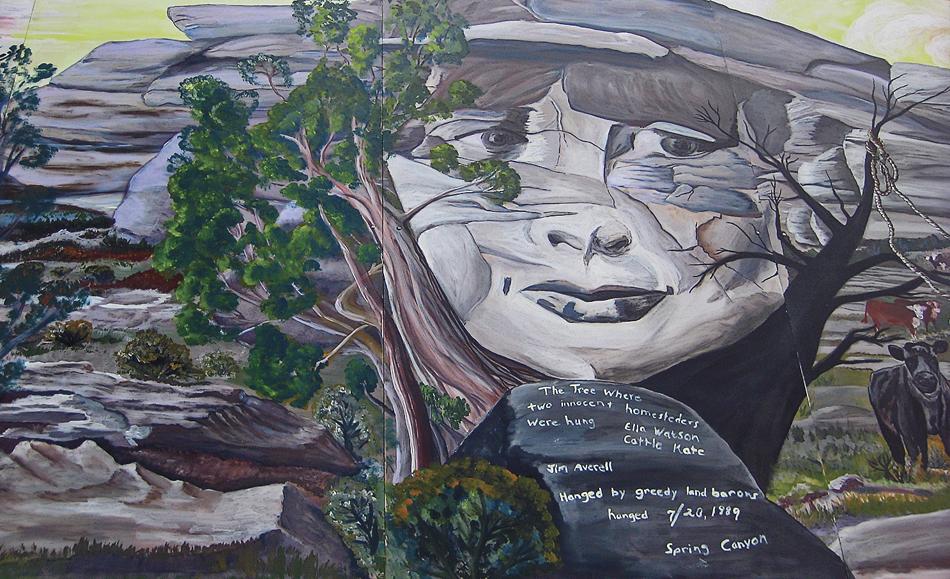

On the 100th anniversary of her murder, Watson’s nieces and nephews gathered in Wyoming to place a marker near where she lay—now under the new Pathfinder Ranch. It read: “These innocent homesteaders were hanged by cattle ranchers for their land and water rights.”

To this day, the city of Rawlins remembers Watson and her murder in its Rawlins Main Street Mural Project, noting she and Averell had been “hanged by greedy land barons.” The mural honors their true characters, declaring, “Ellen and Jim fed the hungry, clothed the naked and took anyone in.”

Jana Bommersbach writes the Old West Saviors column for True West and is a long-time Arizona journalist and author. Her first historical novel, Cattle Kate, was published this fall by Poisoned Pen Press. It’s available in bookstores, from PoisonedPenPress.com or through the author’s website, JanaBommersbach.com

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Hufsmith Collection, Casper College Western History Center –

– By Jana Bommersbach –

– Courtesy Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources –

– By Jana Bommersbach –

– Courtesy Wyoming State Archives, Department of State Parks and Cultural Resources –