Even though Kit Carson’s battle at Adobe Walls was a major engagement, historians have written little about it.

Even though Kit Carson’s battle at Adobe Walls was a major engagement, historians have written little about it.

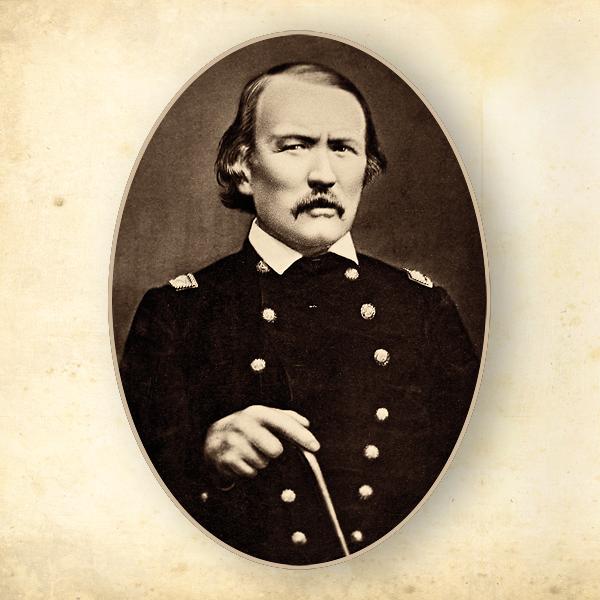

Most people know Carson for his explorations as a mountain man; his adventures with John Charles Frémont, known as the “Great Pathfinder,” in California during the Mexican-American War; and his role in subduing the Navajos and Apaches in Arizona and New Mexico.

Perhaps the Adobe Walls battle received little attention because the numbing effects of the Civil War simply overshadowed it. Most of Carson’s men were seasoned soldiers, having fought at Valverde and in the Apache and Navajo campaigns. They were combat-hardened, tired of marching and ready for action.

One Silent Night

On the evening of November 24, 1864, the troopers had performed their usual camp duties before sunset. Some had begun to eat supper. It was no feast, nor were there special activities to celebrate that eve of the second official, national Thanksgiving Day.

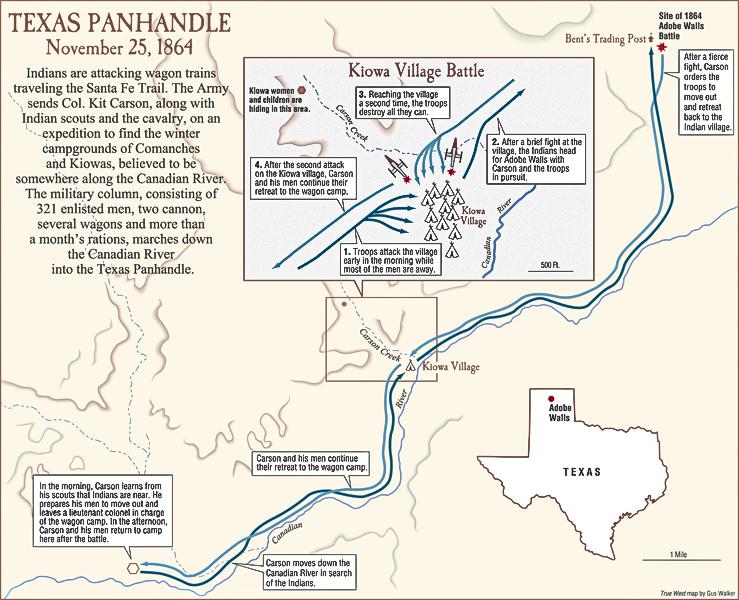

Two Indian scouts Carson had dispatched that morning returned. Upon learning that Kiowas and Comanches were near, Carson immediately set his plan in motion. He split his troops, leaving the wagon train in camp. The Ute and Jicarilla Apache scouts would lead Carson, the artillery and the mounted troops onward.

Instead of rolling out their sleeping blankets, the scouts, cavalrymen and troopers with the two mountain howitzers readied for a night march toward the Canadian River. They filled their canteens, replenished their cartridge boxes and pouches, and stuffed their haversacks with food raided from the wagons.

As they neared the Canadian River, moonbeams revealed impassable red bluffs that dropped several hundred feet to another tributary of the Canadian. In bygone years, the hand of nature had carved a sandy arroyo through the bluffs. The gap was about 10 miles out from camp, where the remainder of Carson’s contingent lay sleeping, and approximately 20 miles west of Adobe Walls, where Kiowas and Comanches slumbered in their tepees.

After picking their way down the steep, rough passage, the troopers followed a fresh Indian trail spotted by the scouts. Carson called a halt until daylight, following a march of about 10 miles. It was a miserable stop. The soldiers were tired, not having slept since the previous night. Their fatigue added to the loathing they felt for their situation, including the hateful no smoking and no talking order. A heavy frost settled on them as they stood beside their horses, reins in hand, for the duration of the night.

The First Shots Ring Out

The troops were in the river channel when they marched out in the early hours of morning. Cane grasses were so tall that Lt. George H. Pettis and Carson, who were riding side by side, had a hard time seeing each other. Continuing their early morning march, they rode in order, with the scouts, Carson and Pettis up front. About half of the cavalry rode behind the scouts, with the section of mountain howitzers close behind the cavalry. The remainder of the cavalry brought up the rear.

The contingent of men and animals must have presented a strange, rather comical, sight. Indian scouts, knees pulled up high and wrapped in conical buffalo robes, appeared as small tepees on horseback. Horses and soldiers labored through tall cane grass, with their breath producing vaporous images like mythical creatures that disappeared and reappeared with each new breath.

After marching about two miles, the troops came to the end of the bluffs, and the terrain opened into about a three-mile-stretch of low, rolling hills cut by small valleys and rivulets. Red hillocks, scattered across the rolling land, brightened the drab, winter landscape.

About halfway across the broad expanse, soldiers heard “Bene-acá! Bene-acá!—Come here! Come here!” The call from Kiowa pickets on the opposite side of the river broke the constant clamor of troop movement. The ever-alert Carson hastily ordered cavalry commander Maj. William McCleave, with B Company, California Cavalry, and Capt. Charles Deus, 1st Cavalry, New Mexico Volunteers, across the river in pursuit of the Kiowas.

In a short time, shots rang out from the detachment Carson had sent to chase the Indian pickets. The shots rapidly multiplied to thousands, as the torturous events of the day unfolded into the First Battle of Adobe Walls.

A Gory Trail toBent’s Old Fort

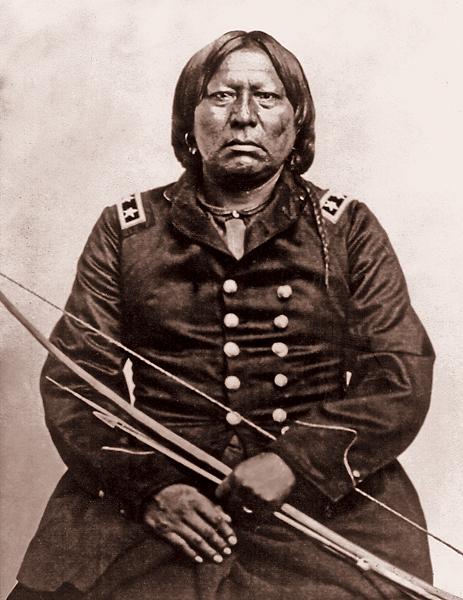

Carson continued his march down the Canadian River. As Carson and his men reached the crest, they could see for two miles across a flat plain. There stood tall, white tents. Chief Dohäsan had chosen his winter camp well. The tall Plains tepees nestled in a flat area surrounded by sand hills on the west, north and east, with the south side opened toward the river. Just north of the village, a clear, running stream flowed around the base of a red bluff. This bluff, along with the other red bluffs Carson had passed near Mustang Creek earlier in the morning, was significant to the Kiowas for winter encampments and sun dances.

The initial clash between McCleave’s troops and the Indians was fierce and brief. It is from the Kiowas’ version that we get a description of the attack. The young Kiowa warriors were in the horse camp when they and McCleave’s troops caught sight of each other. Carson’s Ute scouts advanced, in Indian fashion, riding about and whooping, keeping up a constant yell to stampede the other Indians’ ponies. The soldiers followed quietly in regular order. Most of the Kiowa men were away on the warpath. The warriors who had remained in the village held the soldiers off long enough for the Indian women and children, along with the captives, to escape into the sand hills north of the camp.

With wives and children safely hidden, the Kiowa warriors moved, with haste, across the four-mile stretch down the Canadian River toward Adobe Walls. McCleave and the cavalry were on their tail. The Indians, well acquainted with the area, played it to their advantage, taking protection behind the sandy, gravelly hills that veered toward the river bottom from the north. The battle was hot—each side contested for every foot of ground.

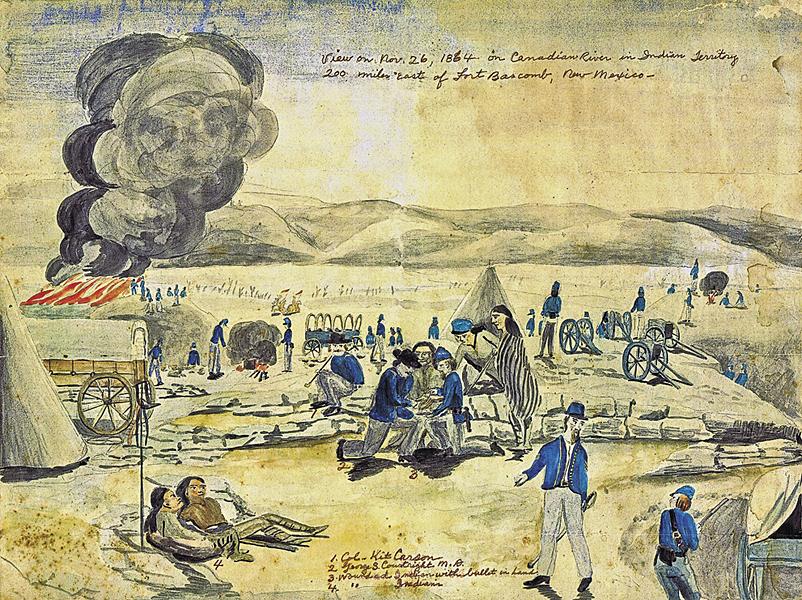

When Carson topped the ridge at Adobe Walls, chances are he recognized the old adobe fort built by William Bent and the surrounding terrain from having been there in 1848, but he had no time for nostalgia. Surveying the scene before him, his quick eye noted Dr. George S. Courtright setting up a medical station inside the walls of the old trading post, where the cavalry had corralled their horses. Looking farther, Carson saw hundreds of Indians charging the troops stationed as skirmishers in the high grass around the foot of the hill.

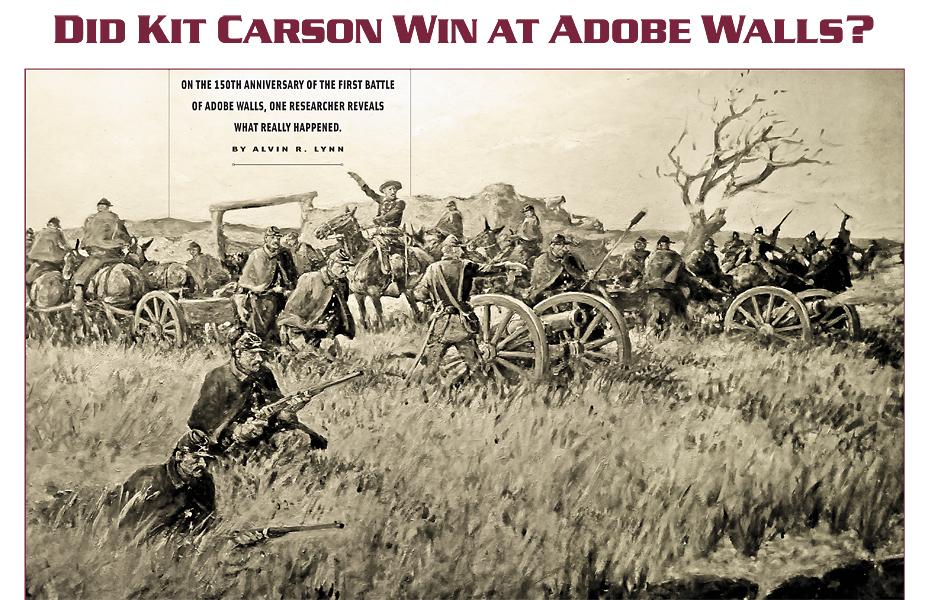

As soon as Pettis’s detail reached the ridge northeast of the adobe fort, Carson yelled, “Pettis, throw a few shell into that crowd over thar,” pointing to about 200 yelling Kiowas and Comanches who were riding back and forth and firing under the necks of their horses at the soldiers. Behind the Indians was a line of 1,200 to 1,400 additional warriors with several chiefs riding up and down the line urging them on.

It took only a short time to load and sight the cannon. The two howitzers belched smoke as their 12-pound, cast-iron balls whistled across the plain toward the mounted warriors. The Indians, not familiar with the big guns, stood high in their stirrups and pondered the firing. As the shells began to explode around them, they headed their mounts, in a dead run, toward their villages downriver.

When the Indians fled after the howitzer shells exploded, Carson thought the battle was over. He called for the cavalrymen to unsaddle their mounts, unhitch them and water the teams at a clear stream west of Adobe Walls. The troops filled their canteens and searched their haversacks for whatever they could find to eat. They had not eaten since the previous evening at Mule Creek before the night march and morning battle. As the troops took their respite in the early afternoon, Carson, ever on the lookout, noticed through his glass a large force of Indians approaching from downriver.

Indians Out for Blood

Responding to Carson’s commands, the officers quickly mounted. Pettis’s men hitched the teams to the artillery pieces and pulled them back to the ridge. The troopers returned their horses to the protection of the adobe fort before they spread out again as skirmishers.

It was only a few minutes before a fusillade of rifle balls flecked the ground around the soldiers. Carson’s troops returned fire, producing a veil of acrid smoke that hovered above them as they crouched in the grass. Pettis’s artillery battery returned to action, but was not as effective as it had been in the morning, for the Indians had learned that they were a more difficult target if they spread out.

By mid-afternoon, Carson realized the gravity of their situation. As he looked downriver, he saw Indian warriors, 10 to 12 miles away, rushing toward battle. The number of Indians had been increasing throughout the day, soon dwarfing Carson’s command of little more than 300. Carson estimated that 1,000 Indians were charging upriver, many of them from a group of 350 tepees standing three miles to the east.

Several Indians passed around the troops riding west toward the Kiowa village that McCleave had ambushed earlier in the day—the village Carson intended to burn before the warriors could recover their livestock and goods. Most of the officers wanted to advance downriver and destroy the large Indian village. Carson, however, considered the wounded men, and, after listening to the advice of his scouts, decided

to retreat.

At about half-past three on the afternoon of November 25, 1864, Carson ordered the command to move out. With calm reserve, gained from more than 30 years of fighting Indians and surviving desperate situations, Carson stationed his troops in strategic positions for retreat back to the Kiowa village.

The Fight for Their Lives

The Indians knew that if the troops reached the village first, it would be torched, leaving them without shelter and supplies for the winter. This stirred the warriors into a frenzy, and they attacked Carson’s troops with death-defying determination.

Carson’s seasoned soldiers had been fighting since early morning, but the fight for their lives was before them. The Indians charged so repeatedly, and with such desperation, that for some time, Carson had serious doubts for the safety of the rear guard. But the steady and constant fire they poured into the Indians caused them to retire on every occasion with great slaughter.

The Indians soon learned that direct charges against Carson’s moving skirmishers were devastating their own ranks, so they devised a scheme to set fire to the weeds and grass behind the soldiers. The dry vegetation burned with intensity, and the east wind pushed the flames dangerously close to the rear of the column.

Carson lit the grass in front of the troops, allowing them to move across the charred ground toward the shortgrass ridges to the right. Near an elongated hill, about 500 yards east of the village, the Indians left Carson’s troops behind and raced ahead to their camp.

Near the Kiowa village, the troopers dismounted at the base of the sand hills and worked their way through sumac bushes to the top of the sand ridges. Using the embankments for protection, the soldiers commenced firing into the Indians who were scrambling to salvage their belongings. After a fierce exchange of fire, and with the aid of the howitzers, the soldiers drove the Indians to the lower end of the camp. Half of the troops set about destroying lodges and property, while the remaining soldiers provided protection with constant fire toward the Indians.

As the sun dropped from the horizon, flames and billowing smoke rose high into the sky, revealing the destruction of the “lodges of the best manufacture.” The glow from the fire illuminated the haggard faces of the spent soldiers as they finished the task before them. A last, parting blast from one of the howitzers propelled a shell toward a group of Indians as they fled toward the river from the south end of the village.

Who Won the Battle?

On the morning of November 27, Carson ordered his command to saddle up and embark on the long trip back to Fort Bascom. Carson did not make the decision rashly. He decided that, due to the circumstances, it was impossible for him to punish the Indians further at that time. He considered the broken-down condition of his horses compared with the quality steeds of the Indians, who had fled in all directions. He didn’t know whether the Comanches downriver had also taken flight or whether they were still nearby with reinforcement recruits joining them. What he did know, however, was that the number of his troops compared unfavorably with the superior number of Indians they had met in battle.

The question of who won the First Battle of Adobe Walls, Carson or the Indians, still resounds. Carson wrote from his camp, “I flatter myself that I have taught these Indians a severe lesson, and hereafter they will be more cautious about how they engage a force of civilized troops.”

The commander of the military district of New Mexico, Gen. James H. Carleton, added his optimistic view of the campaign when he wrote to Carson, “This brilliant affair adds another green leaf to the laurel wreath which you have so nobly won in the service to your country.”

A more accurate assessment of the battle came from the testimony of Brig. Gen. James H. Ford, commander, 2nd Colorado Cavalry, at Fort Larned in Kansas, on May 31, 1865, “I understand Kit Carson last winter destroyed an Indian village. He had about four hundred men with him, but the Indians attacked him as bravely as any men in the world, charging up to his lines, and he withdrew his command….”

The economic loss to the military from the battle was minor compared to that of the Indians. Dohäsan’s people were destitute, but the soldiers had homes waiting for them. The main loss to the military was two soldiers and the death and weakening of horses. Due to the broken-down condition of the Army horses and the lack of soldiers, Carleton planned no other major expeditions into the Texas Panhandle.

As for Carson, in December 1865, he became commander of Fort Union. He remained there only a few months before receiving news of his appointment as brigadier general of the New Mexico Volunteers. In the spring of 1866, he transferred to Fort Garland in Colorado, where he served until he mustered out in the fall of 1867, ending his Army career, which included six years as commander of the New Mexico Volunteer Army that had battled Confederates, Apaches, Navajos, Comanches and Kiowas during his tenure.

This edited excerpt is courtesy Kit Carson and the First Battle of Adobe Walls, by Alvin R. Lynn and published by Texas Tech University Press. A retired social studies and science teacher, Lynn now serves as a steward for the Texas Historical Commission. He lives with his wife, Nadyne, in Amarillo, Texas.

Photo Gallery

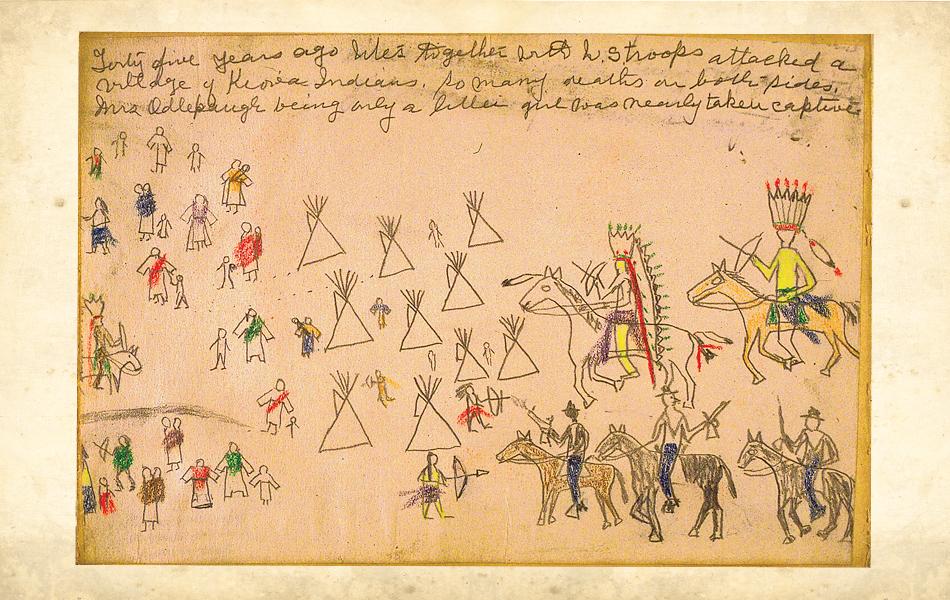

– Courtesy Richard Hogue –

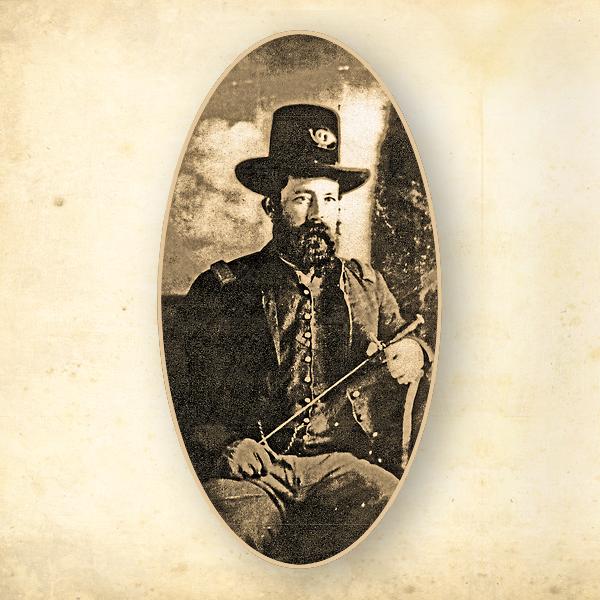

– Courtesy National Park Service, Fort Union National Park –

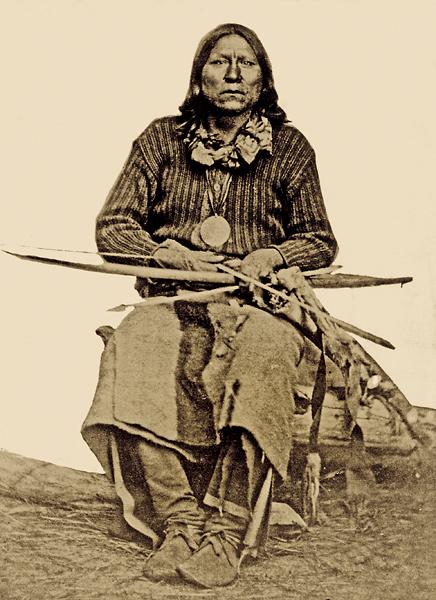

– Courtesy Towana Spivey, Fort Sill National Historic Landmark and Museum, Fort Sill, Oklahoma –

– Courtesy Texas Tech University Press –

– Courtesy American Baptist Historical Society, Atlanta, Georgia –

– Courtesy U.S. Army Military History Institute, Carlisle, Pennsylvania, #246375 Meketa Collection –

– Courtesy Panhandle-Plains Historical Museum #1510/121b –