Born in 1839 in New Rumley, Ohio, George Armstrong (or Autie, as his sister called him) Custer attended Alfred Stubbins Young Men’s Academy.

Born in 1839 in New Rumley, Ohio, George Armstrong (or Autie, as his sister called him) Custer attended Alfred Stubbins Young Men’s Academy.

He graduated in 1855, taught at Beech Point School in Ohio and in 1857 enrolled in West Point, where he was graduated last in his class in 1861. That same year Custer fought in the first Battle of Bull Run and began distinguishing himself as a talented officer, eventually earning brevets as a brigadier general (1863) and a major general (1865). Following the Civil War, with the military rolls reduced significantly, Custer lost his brevetted wartime rank and again became a captain.

On February 9, 1864, Custer had married Elizabeth “Libbie” Bacon, and after the Civil War she joined him on his frontier army assignments. The two wrote often when they were apart, and Custer faced his most serious military reprimand—a court-martial—because of an unauthorized trip across Kansas to see Libbie.

The military unit that became synonymous with the name Custer is one he commanded when it was embroiled in some of the most controversial Indian battles of the 19th century. Promoted to lieutenant colonel, Custer was present at Fort Riley, Kansas, for the organization of the Seventh Cavalry in 1867, and he was with it when he and members of his unit died at the Little Bighorn nine years later.

Hancock’s “Grand Powwow”

The place to begin following Custer’s Western military service, then, is just west of Manhattan, Kansas, at Fort Riley, where Quarters 24, built in 1855, is now known as Custer House even though Custer and Libbie actually lived in Quarters 21A, located down the street. Quarters 21A has been renovated so it has little resemblance to the structure the Custers occupied; Quarters 24 remains virtually unchanged and is now part of the U.S. Cavalry Museum. The museum chronicles service of mounted soldiers from 1776 to the present, and includes Custer’s Seventh Cavalry.

Custer rode from Fort Riley to Fort Larned—a post on the Santa Fe and Smoky Hill Trails that is now a National Historic Site—in March 1867 as part of the Hancock Expedition sent to Western Kansas to effect peace with raiding Indian tribes. (You can take the same general route by following Interstate 70 west past Salina and then Kansas Route 156 southwest to Great Bend, Larned and Fort Larned.) As an officer, Custer had a tent, Sibley stove and food ranging from ham and chicken to pickles and biscuits. The men traveling with the expedition made do with hardtack, a few cans of vegetables and some coffee and sugar, according to Dr. Isaac Coates, the expedition’s medical officer.

During the journey, Custer, who had five dogs and several horses, hunted rabbits and buffalo (even shooting his own horse, Custis Lee, as the steed raised its head just as Custer pulled the trigger to down a bison), before joining Hancock in a “grand powwow” with the Cheyennes.

After the unsuccessful council, Custer led portions of the Seventh Cavalry on west to Fort Hays, now preserved as a Kansas State Historic Site. (To reach Fort Hays from Fort Larned travel north on U.S. 183.) There troops shifted their mission from attempts to scare the Indians to waging war on the tribes in Western Kansas and Southwestern Nebraska. Eventually Libbie joined Custer at Fort Hays, living in a tent camp not far from the soldier bivouac. But when he went out on a scout and conditions became unstable at Hays, she retreated to Fort Riley.

Open Hatred of Autie

During the summer of 1867, Custer earned bitter enmity from some of his troops after he ordered several deserters shot on August 7, and later when he failed to provide protection for other men near Downer’s Station, a stop along the Butterfield Overland Despatch on the Smoky Hill Trail west of Fort Hays. When Custer abandoned his post at Fort Wallace in Western Kansas to visit Libbie at Fort Riley, he faced a court-martial. In proceedings at Fort Leavenworth, he was found guilty of being absent without leave, engaging in improper conduct and ordering deserters to be pursued and shot. Upon conviction, Custer was suspended from his command and had to forfeit his pay for a year, but no criminal charges were preferred and in the fall of 1868, two months before his suspension was to be completed, he was ordered by his mentor Gen. Phil Sheridan to “come quick” in response to escalating Indian trouble on the Western Plains.

Custer rejoined the Seventh Cavalry at Fort Dodge near Dodge City (from Fort Hays take U.S. 183 south), which had not yet come into its own as a booming cowtown. Tensions were rising on the Western Plains, with various skirmishes in Kansas and Colorado. Meantime, Cheyennes under Black Kettle, who had been involved in the 1864 attack at Sand Creek, Colorado, moved south into present-day Oklahoma to camp near the Washita River. During Custer’s raid on Black Kettle’s camp, the flamboyant lieutenant colonel once again took decisive action that carried a stigma of failure after troops commanded by Maj. Joel Elliott became separated from the main body and were annihilated by the Cheyennes. Accusations soon flew that Custer had failed to protect Elliott’s men.

At the Washita, Custer’s men killed Black Kettle and his wife, plus hundreds of horses, before the soldiers destroyed the village and captured over 50 women and children. Many of the women prisoners were sexually assaulted by officers from the Seventh Cavalry and Custer established a long-standing liaison with Monahseetah (Meotzi), daughter of the Cheyenne Little Rock. Their relationship reportedly lasted until Libbie joined Custer in the summer of 1869, when he was again stationed at Fort Hays.

Custer became a bitter enemy of the Cheyennes during those months of service in Kansas, Nebraska and Oklahoma; he would develop equally hostile relations with the Lakotas when the Seventh moved north.

Custer’s Unofficial Black Hills Mission

By 1873, after a period of service in Tennessee, Custer was serving in Dakota Territory—first at Fort Rice and later at Fort Abraham Lincoln, now a state park near present Mandan and Bismarck (on Interstate 94 in Southcentral North Dakota). On July 2, 1874, he led a surveying expedition of around 1,000 men, 110 wagons and hundreds of mules, horses and cattle from Fort Lincoln into the Black Hills of Western South Dakota and Northeastern Wyoming. (Follow the Missouri River south from Mandan on North Dakota Route 24 past Fort Rice to South Dakota Route 63 and U.S. 12 to Mobridge, and then take U.S. 83 through Pierre to Interstate 90 and follow it west to Rapid City and the Black Hills.)

Custer had orders to explore and locate a potential site for a fort in the Black Hills and to establish a route to Fort Laramie. On the side, and unofficially, Custer’s expedition was also tasked with determining whether there was truth to the rumors of gold in the Black Hills.

By late July, Custer’s party had established a camp south of Harney Peak, near the present-day town of Custer, South Dakota (southwest of Rapid City on U.S. 16). While some of the men climbed the peak, others mapped the area. The unit then traveled west into present-day Wyoming where Custer climbed Inyan Kara Mountain, south of Sundance, and carved his name on the rocks. (Take U.S. 16 west to Newcastle, Wyoming 116 to Sundance, then U.S. 14 and Wyoming 24 past Devil’s Tower and through Hulett and Aladdin to follow Custer’s basic route.)

While in the Black Hills, Custer’s party learned of civilian miners who had found gold in the region. He returned to Fort Lincoln, but word about gold in the Black Hills quickly spread to Fort Laramie and the rush began, setting the stage for a final showdown with the Lakotas and their allies.

The Black Hills, now known for Mount Rushmore and the emerging rock memorial to the Lakota leader, Crazy Horse, had been set aside for the tribes under the 1868 treaty negotiated at Fort Laramie. But upon learning of the presence of gold, miners began encroaching. Soon the sheer numbers of invading whites made it impossible to retain the territory for the tribes, as towns like Deadwood sprang up.

Persona Non Grata

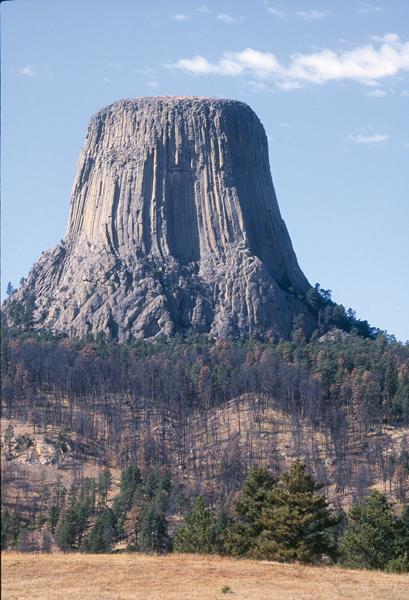

Having made enemies of the Southern Cheyennes at the Washita, Custer had now become persona non grata to the Northern Cheyennes and Lakotas, who considered the Black Hills, Bear Butte and Bear’s Tipi or Mato Tipila (Devil’s Tower) sacred ground. Although some Lakotas adhered to the 1868 treaty and lived on the Great Sioux Reserve, others led by Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull continued roaming freely. They had conflicts with railroad construction workers laying tracks across the Dakotas and into Montana and had joined forces with the Cheyennes and Arapahos by early June 1876, setting the stage for Custer’s last command.

As Libbie watched on May 17, 1876, the Seventh Cavalry left Fort Lincoln, riding behind Custer to the strains of “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” played by the Seventh Cavalry Military Band. This regiment was part of a three-prong plan orchestrated by Gen. Alfred Terry. Colonel John Gibbon was expected to move in from the west, with Terry and Gen. George Crook advancing from the south. The three military bodies would converge on the Indians, eventually forcing them onto reservations. But Custer’s ride to the Little Bighorn (in Southcentral Montana on Interstate 90 at Hardin), which native tribesmen called the Greasy Grass, ended not in glory but in death.

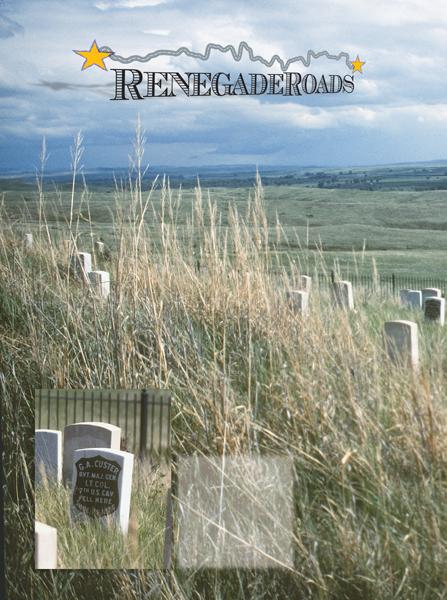

On June 25, a superior force of Indians surrounded Custer and his immediate command after they became separated from the other units. The man Libbie had followed across Kansas to Tennessee and then to Dakota Territory died at the Little Bighorn along with much of the Seventh Cavalry, including four members of his own family: brothers Capt. Tom Custer and Boston Custer, brother-in-law Capt. James Calhoun and nephew Autie Reed.

The Custer guidon had fallen.

Candy Moulton is the author of Roadside History of Wyoming and other Western history books.

Photo Gallery

– By Karen A. Robertson –

– True West Archives –

– All photos by Candy Moulton unless otherwise noted –