Our usually quiet city was startled last Tuesday by one of the most cold-blooded murders, and heavy robberies on record,” The Liberty Tribune reported February 16, 1866.

Our usually quiet city was startled last Tuesday by one of the most cold-blooded murders, and heavy robberies on record,” The Liberty Tribune reported February 16, 1866.

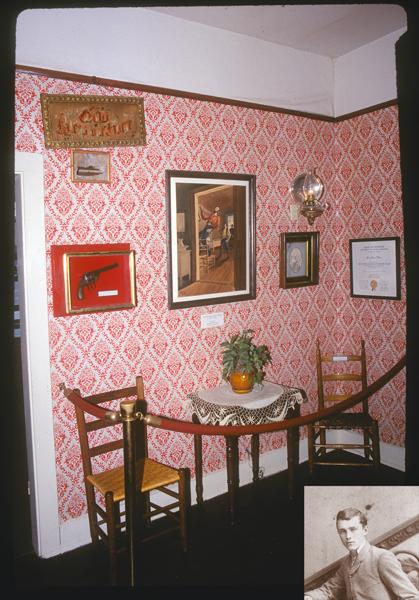

Liberty, Missouri, is still usually quiet, as is the Clay County Savings Association that was robbed on February 13, 1866, “by a band of thieves and murderers” who killed one innocent bystander that frigid afternoon. The bank, rechristened the Jesse James Bank Museum, has been restored to look pretty much how it did when the James-Younger Gang began its road to infamy or glory or both—depending on where you stand.

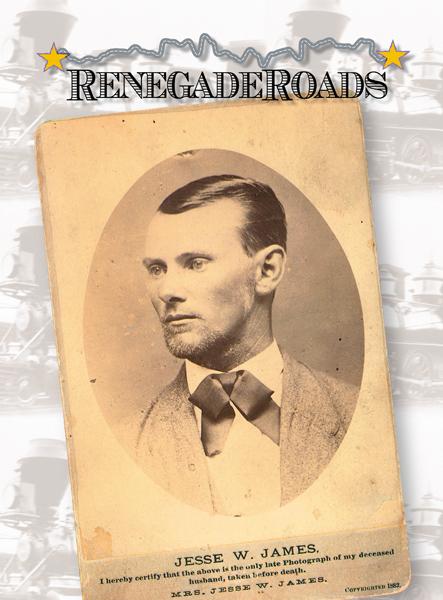

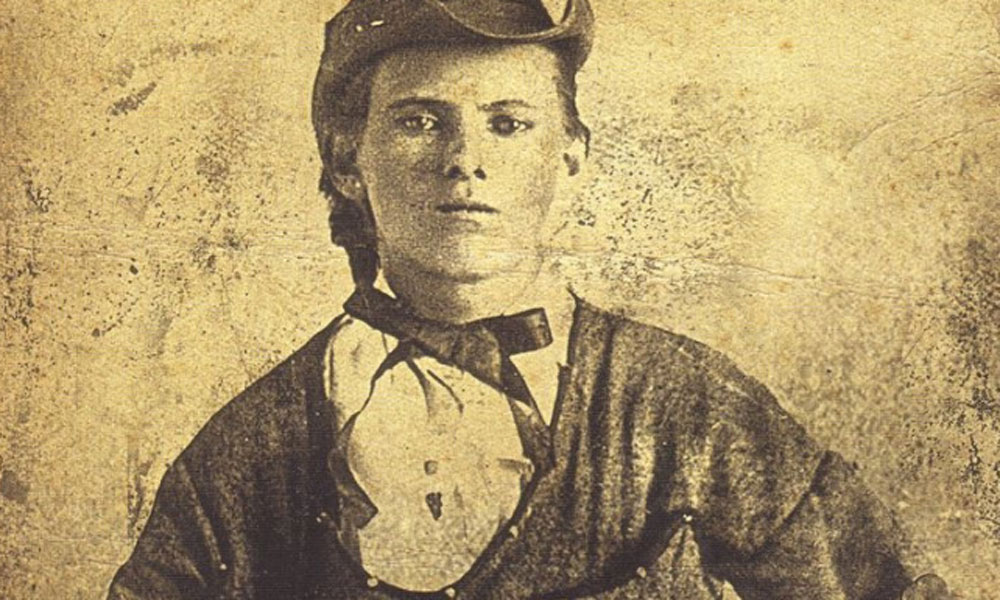

Then again, you really can’t prove that Jesse James or older brother Frank ever robbed any bank or train. Jesse was killed without benefit of a trial, Frank was acquitted and Cole Younger never named names. Nor can you really prove which banks and trains “the boys” (as they are called today, at least in Missouri) robbed and which ones other border ruffians held up and passed on the credit to the James-Younger Gang.

History and urban development have wiped out many of the old sites, but Liberty endures. So if you’re following Jesse James, the town square’s the perfect spot to start a Renegade Road.

Independence Day

From Liberty, I drive to Independence and check into the Woodson Guest House, a charming antebellum home-turned-B&B. Woodson? Isn’t that Jesse’s middle name, from his great-grandmother Elizabeth Woodson? Didn’t Frank often use Woodson as an alias? Is this a mistake? Am I about to check into some Bates Motel and never check out? Actually, there’s probably no connection between Samuel Woodson, who built this house, and the boys, but the B&B isn’t far from the graves of Frank and Annie James at Hill Park Cemetery. And my only danger from innkeeper Charlotte Olejko is being overstuffed with breakfast before being sent on my way to tour historic Independence.

Pioneer Trails Adventures offers wagon tours of the area around Independence Square, but my main reason for visiting Harry Truman’s hometown is the 1859 Marshals Home and Jail, an uninviting name for a great museum. The two-story Jackson County Jail housed Frank James after he surrendered in 1882 until he was shipped up to Gallatin to stand trial in 1883 for the Winston train robbery.

South of Independence, I find the graves of Cole Younger and brothers at Lee’s Summit Historic Cemetery. Then it’s on to Lexington, where—could it be?—Jesse pulled off the first liquor store robbery.

Okay, maybe not. But Fredrikson’s Fine Wine and Spirits once housed the banking institution of the Alexander Mitchell and Company instead of Pinot Grigio and single-malt Scotch. On October 30, 1866, two to four unidentified men robbed the bank of $2,000 and change. Was Jesse one of them? Some historians scoff at that notion, but I know better than to argue with locals in Missouri.

Of course, you couldn’t blame the boys for wanting to visit Lexington. The antebellum homes are marvelous, and Civil War buffs are sure to enjoy the Lexington Battlefield.

On to Richmond

Nor could you blame the boys if they robbed the bank just up the road in Richmond, maybe the friendliest town in Missouri. It wasn’t so hospitable on May 23, 1867, when 11 to 20 outlaws took the Hughes and Wasson Bank for $3,500, and in the resulting carnage, three citizens were killed. Legend has it that this bank, now an office building, was robbed six times between 1866 and 1867. Ex-Confederate guerrillas didn’t care much for Richmond, it seems, because of the way townsfolk and federals had treated the remains of Bloody Bill Anderson.

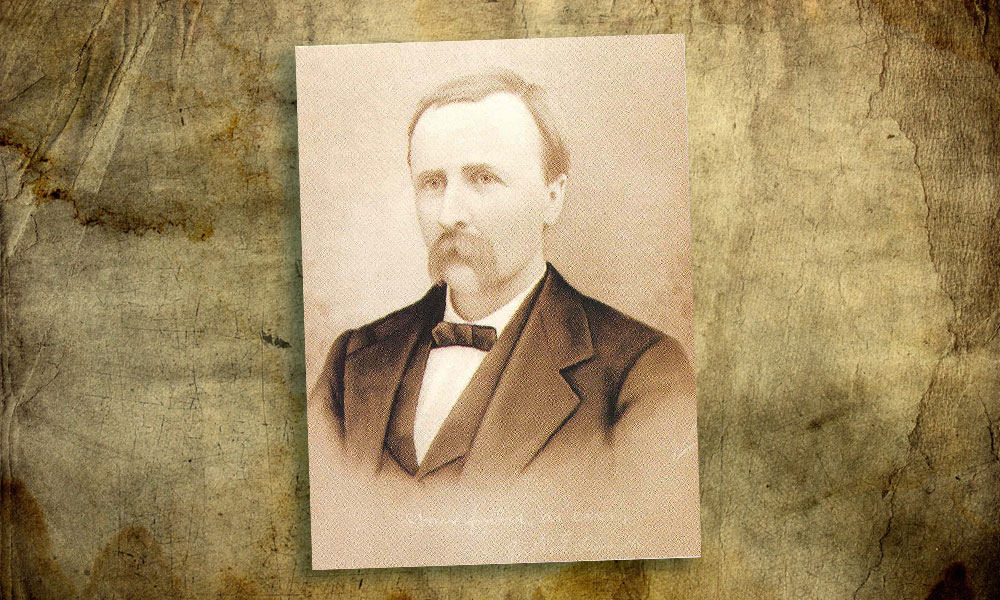

Another Jesse robbery? Probably not, but Richmond’s worth a visit for a couple of graves: Bloody Bill’s and Bob Ford’s. Ford’s headstone has been chipped away to the base, but there is a marker over his grave, although the year of his birth is well off the mark. Ford became The Man who Killed Jesse James in St. Joseph in 1882. Ten years later, Ed O’Kelly became The Man who Killed the Man who Killed Jesse James when he blew Ford away in Creede, Colorado. And in 1904, policeman Joe Burnett became The Man who Killed the Man who Killed the Man who Killed Jesse James when he blew O’Kelly away in Oklahoma City.

Do you see a trend here?

Where else? Gads Hill? Glendale? Winston? Kentucky, Alabama or Tennessee? If you truly want to follow Jesse’s trail, first buy stock in Chevron because the boys got around. I’ll make things easier and drive to Kearney.

Home country

The old family home, now the Jesse James Farm and Museum, is where Jesse was first buried in 1882 (he was reinterred at Mount Olivet Cemetery in town in 1902).

The 1822 cabin (plus the prefab addition Frank added to appease his wife) is open for guided tours (no photography inside). It was here in 1875 that the Pinkertons tried to send the James Gang into oblivion, but succeeded only in blowing off Jesse’s ma’s arm and killing his eight-year-old stepbrother, Archie Peyton Samuel.

Dumb move.

Maiming women and killing kids didn’t go over well in Missouri in the 1870s, and this little incident probably did more to fuel the myth of the boys as good lads fighting injustice than anything else.

A Bullet for Jesse

The end came for Jesse in St. Joseph, where his final residence, now the Jesse James Home, is a museum that includes artifacts as well as exhibits dealing with the 1995 exhumation and DNA tests that proved to most people, but certainly not everyone, that Bob Ford did kill Jesse here.

While in St. Joe, check out the nearby Patee House Museum, a fantastic museum, and the Missouri Valley Trust Bank Building. Some think that Jesse cashed a $100 bill at the bank before Ford killed him. Was Jesse planning on robbing it? History says he wanted to hit a bank in Platte City instead.

Before leaving St. Joe, diehard Jesse James fans will want to visit the Buchanan County Courthouse. Bob and Charlie Ford were tried for Jesse’s murder here, pled guilty and were sentenced to hang. Governor Thomas Crittenden pardoned them.

St. Joe’s the perfect place to end the Jesse James Trail. After all, this is where it all ended, but the James Gang is more than Missouri. So head up I-29 to Nebraska.

Go Big Red

Not that Cornhuskers remember much about the James Gang, as Omaha prefers to concentrate on things like Lewis and Clark, the Union Pacific and the George Crook House, but Frank and Annie eloped here and, down in the southeastern corner of the state, Jesse was nursed back to health in Rulo after being shot in the lung in 1865. The boys planned a caper or two in Franklin, too.

Jesse and pals spent a good bit of time in Nebraska, and who could blame them? They probably stocked up on Omaha Steaks and bought authentic custom-made cowboy hats at the Great Plains Hat Co. in Bellevue.

Then they went east on I-80.

Fields of Dreams in Iowa

Adair is just a bump on the road in Iowa, but it’s one of the most important stops along the Jesse James Trail. On July 21, 1873, the James-Younger Gang pulled its first train robbery.

The boys derailed the train, which killed the engineer and sent the engine, tender, baggage and express cars sliding down the embankment. Confused, the bandits made off with between $1,700 and $3,000. They left behind 3.5 tons of gold bullion.

Well, the boys did improve their M.O. after that first botched job, which is marked at a roadside park a short drive from the interstate. At least, they stopped derailing trains.

From Adair, I move east to U.S. 169, then head south to Madison County and the friendly town of Winterset.

Bridges, a Duke and a Joke

Okay, there’s absolutely no proof that Jesse ever hung his hat in Winterset, although several of the famed covered bridges date to his era. But there’s no way I’m passing up the opportunity to visit the birthplace of John Wayne.

In 1907, a female doctor delivered a 13-pound baby boy named Marion Robert Morrison (the family unofficially changed the middle name to Michael after the Duke’s brother was born) at this home, now a museum and gift shop. Besides, I need to take a break from all this murder and violence, and Winterset’s a fine respite. The folks at John Wayne’s home are friendly, and the bridges of Madison County are worth viewing, although I cringe when I drive by one of the structures destroyed by arsonists.

Criminy, even Jesse wouldn’t have done that.

Farther south, on State Highway 2 is Corydon, where the boys (probably Frank, Jesse, Cole and Clell Miller) robbed the Ocobock Brothers’ Bank of between $6,000 and $15,000 on June 3, 1871. The safe from that robbery is displayed at the Frontier Trails Museum of Wayne County, open April 15-October 15 or by appointment.

Legend has it that, on the way out of town, Jesse interrupted Henry Clay Dean’s speech at the Methodist church, saying the bank had just been robbed. The crowd admonished him to shut up.

Of course, the boys were in no joking mood at the final stop on the Jesse James Trail. From Corydon, double back to I-35 and head north to Rice County, Minnesota, and up State Highway 3 to Northfield.

The Great Northfield Raid

Founded on the Cannon River in 1855, Northfield became one of the most recognized cities in Western history on September 7, 1876. That’s when the boys decided to rob the First National Bank.

Northfield takes pride in its heritage, from the restored bank and museum to the Defeat of Jesse James Days festival the weekend after Labor Day. The local CVB provides a self-guided tour brochure of the “Outlaw Trail,” following the route the boys took during their swing through the area. Guided tours can also be arranged. Rest assured, Northfield’s tour guides are better than Bill Chadwell.

Jesse figured Minnesotans for cowardly farmers and thought Chadwell would guide the gang out of town and back south to safety. The good folks of Northfield, however, took exception and shot the boys to pieces, leaving Chadwell and Clell Miller dead on the streets. The Youngers were captured at Hanska Slough, where Charlie Pitts was killed. Meanwhile, Frank and Jesse scurried out of Minnesota.

Northfield’s victory proved costly. Cashier Joseph Lee Heyward and Swedish emigrant Nicholas Gustavson were killed, but Defeat of Jesse James Days is aptly named.

The moral of this Renegade Roads? Perhaps Cole Younger put it best:

“There is no heroism in outlawry, and the fate of each outlaw in his turn should be an everlasting lesson to the young of the land.”

Like Frank and Jesse James, Johnny D. Boggs is a staunch believer in lost causes in Missouri: He’s a longtime Kansas City Royals fan.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Johnny D. Boggs unless otherwise noted –

– Bob Ford photo courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –