Everybody is soooooo nice in Bonham, Texas, I find it hard to believe that this is the place that gave birth to a psycho, bigoted, cold-blooded murdering SOB like John Wesley Hardin.

So when I ask the docent at the Fannin County Museum of History about Hardin, she gives me this suspicious look and says, “Oh, my… him.” The same look and tone a journalist in Timmonsville, South Carolina, would get after asking someone about me.

Actually, Hardin wasn’t born in the city limits, but at Blair’s Springs about 10 miles southwest of this north Texas town. Besides, as Leon C. Metz points out in his brilliant biography, John Wesley Hardin: Dark Angel of Texas, Hardin “had little if any recollections of his youth there. Instead, his memoirs picked up in the East Texas piney woods of Polk County near the tiny community of Moscow when John was sixteen.”

You won’t see much in Moscow, an unincorporated community about 90 miles north of Houston. Yet Bonham offers lots to see, so here I am.

A good place to start is the Fannin County Museum of History. Located in a 1900 Texas and Pacific Railway Depot, the museum chronicles the region’s history, beginning with the prehistoric era while focusing primarily from the region’s settlement during those turbulent Texas revolution years through WWII.

For a better look at what life would have been like, check out Fort Inglish Village. Open Tuesdays through Saturday from April 1-September 1, the replica of the fort established by Bonham’s founder Bailey Inglish was built in 1976. Three log cabins from the 1830s have been relocated outside the stockade. The site also includes a school/church. Interpreters demonstrate skills such as making lye soap, brooms and candles, and student visitors can grind corn or hand wash clothes. No wonder Hardin would have few memories of life around Bonham. I’ve tried to block those memories of farm chores myself.

Hard Times, Bad Man

John Wesley Hardin was born on May 26, 1853, the son of J.G. Hardin, a Methodist minister and circuit rider, and Elizabeth Hardin, “blonde, highly cultured, and charity predominated in her disposition,” as Hardin remembered in his autobiography.

He was a product of his times, and those times after the Civil War were hard. In 1868, he shot a black man he claimed was bullying him. “To be tried at that time for the killing of a Negro meant certain death at the hands of a court, backed by Northern bayonets,” he wrote.

Hardin became a fugitive. By the time he was captured, tried and sentenced to prison a mere 10 years later, he had killed more than 20 men. He claimed 42.

Hardin’s trail covered much of the West and much of the South. You can visit Abilene, Kansas, where he claimed (I think he was full of horse apples) to have backed down gunfighter Wild Bill Hickok. You can visit Pensacola, Florida (or better yet, those white sand beaches in Destin), where he was captured by Texas Rangers and local Florida lawmen in August 1877. He hung out, or hid out, in Louisiana and Alabama too. But for this Renegade Road, I’ll stick to Texas. After all, Texas made him.

Rangering On

Next stop: The Texas Rangers Hall of Fame and Museum in Waco.

The Rangers got involved in the chase of Hardin after he killed Comanche County Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb in 1874. After Ranger Jack Duncan located Hardin in Alabama and Florida, Ranger Lt. John B. Armstrong, who had served under the legendary Ranger Capt. Leander McNelly, asked to work the case.

Hardin got on the train in Pensacola, and Armstrong boarded the coach. Stories vary after that, but the end result is that Hardin was knocked out, another man was killed and Hardin was captured at last.

Armstrong wound up in the Texas Rangers Hall of Fame, along with other legendary Rangers, such as McNelly, Sam Walker, John S. “Rip” Ford, John Coffee Hays and James Gillett. The museum covers about every aspect of the Rangers, from history to pop culture (yes, Chuck Norris and his TV show Walker, Texas Ranger get plenty of coverage). It is home to artifacts galore, artwork and an extensive firearms collection that seems to grow every time I visit this museum.

Before the Rangers stepped in, Hardin’s legend had grown tremendously, so I’m bound for his old stamping grounds in Gonzales and Cuero.

South Texas Feuds

Cuero was founded in 1872 on the Chisholm Trail. It also had a place in John Wesley Hardin lore.

Hardin killed stonemason J.B. Morgan—his 13th victim, according to Metz—in Cuero in 1873. In a saloon on the town square, Morgan had asked Hardin to buy him a bottle of bubbly. Hardin didn’t want to. Morgan insisted. Hardin left the saloon. Morgan followed and asked if Hardin was armed. Hardin nodded. Morgan said, “Well, it’s time you were defending yourself,” and went for his gun. Bad mistake.

“I pulled my pistol and fired,” Hardin wrote, “the ball striking him just above the left eye. He fell dead. I went to the stable, got my horse, and left town unmolested.”

Later, Hardin killed Sheriff Jack Helm in Albuquerque. Hardin had left his horse at the blacksmith’s shop when he turned to see Helm approaching Hardin’s friend Jim Taylor with a knife. “Someone hollered, ‘Shoot the d—-d scoundrel,’” he recalled. “It appeared to me that [Helm] was the scoundrel, so I grabbed my shotgun and fired….” Then he pointed his gun at townspeople, while Taylor shot Helm several times in the head.

This was all part of the Sutton-Taylor Feud, perhaps the state’s longest and most violent feud (not counting the University of Texas-Texas A&M rivalry). The Rangers were called in, but even they couldn’t bring peace, which didn’t occur until after Jim Taylor was killed on December 27, 1875.

Times are more peaceful now, but you can get history lessons at the Dewitt County Historical Museum. The Cuero Heritage Museum and the Hochheim and Taylor-Bennett cemeteries are also worthwhile stops.

Another must-stop is Gonzales.

Hardin was never held in the Old Jail (it wasn’t built until 1887) but the restored jail, which was in use until 1975, has a small display focused on Hardin.

For a taste of the lives of early Texas pioneers, I head over to the Gonzales Pioneer Village, a living-history center with nine homes, businesses and outbuildings from the county, and the circa-1848 Eggleston House, a furnished log home. If you’re a Texas Revolution buff, then you should also be sure to check out the Gonzales Memorial Museum.

Next stop: The one jail strong enough to hold Hardin.

Doing Time

The state pen in Huntsville was no place to be in the 1870s. Hardin was often flogged—well, he was trying to escape—in those early years of imprisonment. Huntsville’s prison is still no place to be, but the museum is not to be missed. Several exhibits showcase the history of the prison, telling the story from the viewpoints of prisoners as well as guards.

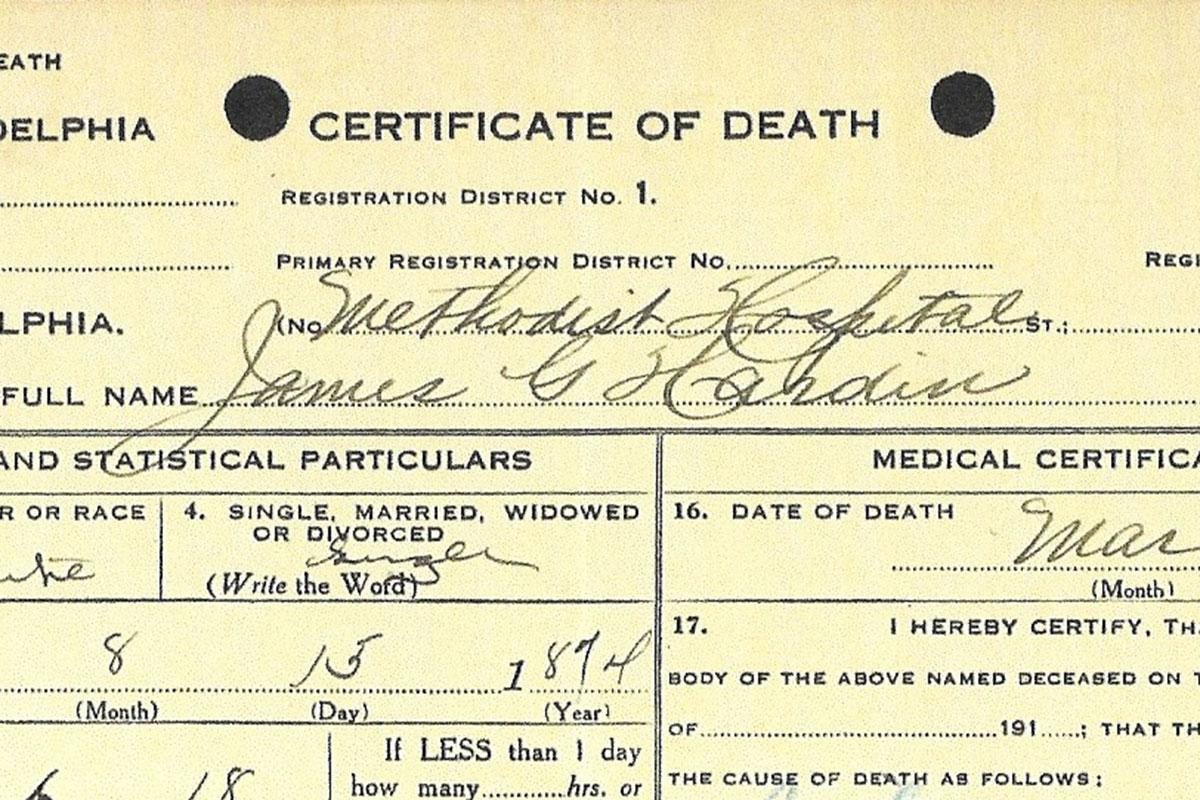

Exhibits include histories of some of Huntsville’s famous residents, including, naturally, Hardin, who was released from prison in 1894, after serving 16 years of a 25-year sentence. Shortly afterward, he was pardoned. He later passed the state bar and became a lawyer.

Hardin’s prison sentence had its foundation in Comanche, so I’m off there. First, I stop in Fort Worth, because Cowtown is never to be

missed. Fort Worth also played a part in the Hardin story. On his way to Huntsville, he stopped in Fort Worth, where the “people turned out like a Fourth of July picnic, and I had to get out of the wagon and shake hands for an hour before my guard could get me through the crowd.”

Comanche Stories

In Comanche, Hardin’s reception was a little less popular.

In 1874, Hardin, Jim Taylor and others were celebrating Wes’s 21st birthday in a Comanche saloon. Brown County Deputy Sheriff Charles Webb arrived, but he said he had no warrants for Hardin. One thing led to another, and before long—typical for Hardin—Webb was shot dead. Hardin fled. Vigilantes later lynched Hardin’s brother, Joe, and cousins Tom and Bud Dixon. After his capture by the Rangers, Wes Hardin returned to Comanche to stand trial for Webb’s death, and the jury found Wes—who claimed self-defense—guilty of second-degree murder.

Opened in 1975, the Comanche County Historical Museum shares plenty of information on Hardin. It even houses an exhibit on the saloon gunfight that left Webb dead. Outside you’ll find the remains of the oak tree that held the hanged bodies of Hardin’s brother Joe and the Dixons, who are buried at Oakwood Cemetery.

Eventually, Wes Hardin would join them in death, so I’m off to the end of Hardin’s trail in El Paso.

El Paso

Hardin hung up his shingle in El Paso. But, as Johnny Cash sings on his 1965 album Ballads of the True West (yes, Cash was paying tribute to this magazine):

You won’t find him there for business

Every day at nine

For business is real bad

One client’s all he’s had

In quite a long, long time

One of those clients was Helen Beulah M’Rose. Well, she was more than just a client. She became, as Cash sings, “Wes’s woman.”

El Paso, however, wasn’t so good for Hardin. He gambled. He drank. He quarreled with Constable John Selman. On August 19, 1895, Hardin was playing dice at the Acme Saloon. A little before midnight, Selman entered the saloon with his .45 already drawn and commenced firing. Hardin fell dead.

As Metz writes: “At a little over forty-two years of age, John Wesley Hardin had outlived his era. He was an anachronism, a psychopathic gunman out of the past, a man more or less waiting to be buried.”

Hardin was buried—M’Rose paid for his funeral—in Concordia Cemetery, a vast boneyard that’s definitely worth a visit. But don’t forget to check out the El Paso Museum of History and its “Changing Pass” exhibit that takes visitors through the major events that helped shape this city.

Selman was tried for murder, but it ended in a hung jury. A retrial did not take place because, on April 5, 1896, Deputy U.S. Marshal George Scarborough shot down Selman, who died that afternoon during surgery.

Selman was buried in Concordia too, not far from Hardin’s grave.