Many classic Westerns feature the timeworn device of the last-minute cavalry rescue.

The baddies are Indians, besieging a wagon train or surrounding a mixed group of stranded stagecoach passengers. Just when things appear bleakest, in ride the boys in blue, guidons flying and bugle blaring. This dramatic motif has a historical basis. We know of at least two instances in which the cavalry did arrive at the last minute—and altered the course of history.

Lincoln County, New Mexico, 1878

A struggle had been playing out for a year and a half between two contingents, Tunstall-McSween and Murphy-Dolan, each hoping to gain economic control of the region. Precipitated in part by the arrival of a naïve, self-absorbed, 24-year-old Englishman named John Henry Tunstall, the rivalry soon deteriorated into a bullet-driven fight for supremacy. The law was twisted and used by both sides to further their ends, and when that failed to serve, unadorned murder took its place.

The killing of Tunstall would enrage his ranch hands, including William Bonney, later known as Billy the Kid. His faction, just like the other, had its share of man-killers, duly deputized and sent out to serve warrants in whatever fashion they deemed appropriate. No one was blameless. By the time the battle wound down, about 20 men were dead by gunshot, martial law had been requested (yet not declared) and a new governor was in charge.

One of the deciding events in the Lincoln County War occurred on July 19, 1878.

For five days already, some 40 armed members of the opposition, including Sheriff George Peppin and outlaw John Kinney and his gang, had been firing into lawyer and former Tunstall partner Alexander McSween’s house. McSween and some 12 Regulators—including Bonney—had forted up inside the house, along with McSween’s wife, sister-in-law and her children. The McSween faction did not seem to have much “show” of getting away, although they were firing back.

At nearby Fort Stanton, the portly and pompous Col. Nathan A.M. Dudley was considering a course of action. Just one month earlier, Congress had passed a law forbidding the army from interfering in civilian matters without the express permission of the president. This “Posse Comitatus Act” had prevented Dudley from supporting Sheriff Peppin with troops two weeks earlier. Now, however, he decided to act autonomously. After a brief meeting with his officers, in which they signed a resolution to “place soldiers in…Lincoln for the preservation of the lives of the women and Children,” Dudley led 35 cavalrymen into Lincoln, carrying three days’ rations and towing a 12-pound mountain howitzer and a Gatling gun with 2,000 rounds of ammunition.

Unfortunately, Dudley was not objective; he personally despised the McSweens, and he had been thoroughly won over to the Murphy-Dolan camp. With his presence in Lincoln, the outcome of the siege became a foregone conclusion. So confident of Dudley’s support were Peppin’s men that they occupied the houses surrounding McSween’s. From the doorway of one arrogantly hung a black flag, signifying “no quarter.” In response to a distraught Mrs. McSween’s query about her husband’s safety, Dudley dissembled, “I give you my word of honor, as an officer of the army, that he will not be molested or in any way hurt.”

After one of the civil officers tried unsuccessfully to serve warrants on McSween’s men, Dudley stood by as Peppin’s men set fire to the house and the gunfire between the factions intensified. As night fell, the besieged men broke for safety; while a handful escaped, some were killed and others wounded. McSween, unarmed, was shot down as he pleaded for mercy.

At the least, the soldiers did nothing to stop the carnage; Bonney, however, later claimed that several troopers were among those who fired at the escaping men. Nor did the soldiers intervene when the Peppin posse drank themselves stupid, looted McSween’s store and ranged through the town firing their weapons. The bodies lay where they had fallen.

This was not the cavalry’s finest hour. Mrs. McSween hired a lawyer to petition for Dudley’s court martial. The colonel was no stranger to courts-martial, having already been found guilty of various charges twice in his military career. In this battle, he had defied the new law barring army interference and assumed a partisan position in a deadly feud among private citizens. At Gov. Wallace’s request, Dudley was relieved, but subsequent efforts to find him legally culpable in the “Big Killing” proved fruitless.

Johnson County, Wyoming, 1892

The wealthy and powerful Wyoming Stock Growers Association met in Cheyenne and decided to put an end to the cattle rustling in Johnson County. Their concept of “rustlers” encompassed all small ranchers, maverickers and basically anyone—including the sheriff—whose views differed from their own. They assembled an army of roughly 50 men, including less than two dozen hired killers from Texas, and invaded Johnson County. They had the support of the governor, the former governor, two senators and, ultimately, President Benjamin Harrison—and they were completely in the wrong.

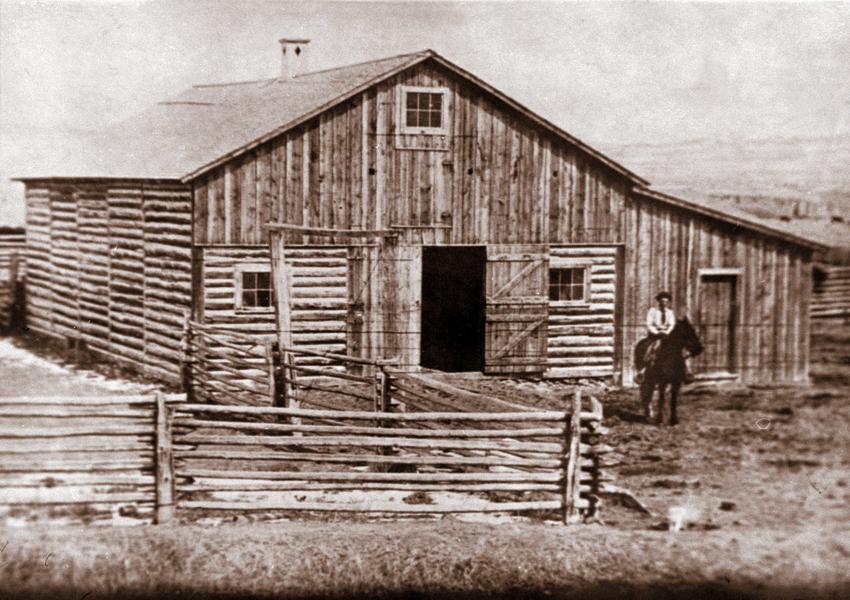

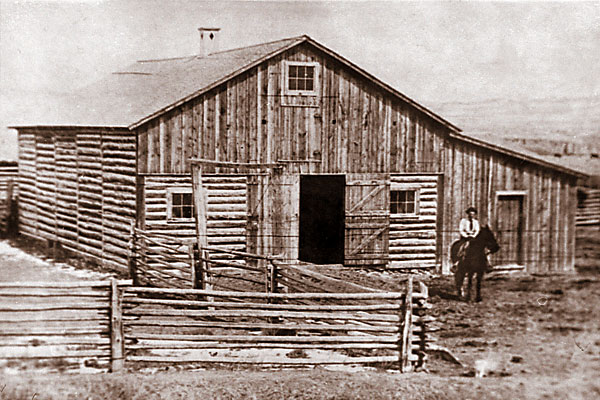

In April they set forth, well-armed and provisioned, with a death list containing dozens of names. After brutally killing two ranchers and burning their cabin, they were trapped inside the barn and ranch house of an ally, as hundreds of outraged townsfolk imposed a siege. From two Studebaker wagons, the furious locals constructed a mobile assault vehicle—a “Go-Devil,” as they styled it—behind which to advance and kill the Invaders.

Early on April 13, the Go-Devil was wheeled to within 200 feet of the barn; that was as far as it would ever go. At 6:45 that morning, a contingent of 107 troopers of the Sixth Cavalry from nearby Fort McKinney rode in and ordered the immediate cessation of hostilities. With the safety of the territory’s cattle barons and their minions at stake, the soldiers were acting under direct orders from President Harrison, at the urgent prodding of Acting Gov. Amos W. Barber and as accorded by Article IV, Section 4 of the U.S. Constitution.

The Invaders were allowed to surrender to the military under a flag of truce—a serious breach of civil law. Quartered at the fort, the cattlemen and their gunmen were treated more as guests than prisoners. Gradually, every member of the invading army quietly drifted back home.

Not a single man was ever punished for the armed invasion of an American territory. Thanks to the timely arrival of the U.S. Cavalry, the wrong guys were saved.

Ron Soodalter is the author of Hanging Captain Gordon and The Slave Next Door, and has written articles for Smithsonian, Civil War Times, Portland and New York Archives and is a featured columnist for America’s Civil War.

Photo Gallery

– All images courtesy Johnson County Library –

This photograph was taken shortly after the cattlemen and their hired gunmen were taken into custody.