In a sense, Pete Kitchen represented Arizona’s transition from

lawless frontier to civilization. In 1861, the U. S. Army was withdrawn

from Arizona to fight in the Civil War that raged in the East. The

Apache and other lawless elements seized the opportunity to ravage

the settlers in Arizona. Travelers were murdered daily on the roads

leading out of Tucson. The bloody road that passed by Pete’s ranch

was christened, “Tucson, Tubac, Tumacacori, To Hell.”

Pete’s ranch on Potrero Creek became the only safe haven

between Tucson and the Mexican village of Magdelena. Located atop

a hill with a commanding view in all directions, his ranch house

became a veritable adobe fortress. It was extremely difficult for an

enemy to approach, and Pete had a sixth sense about Apache

warriors and border bandits. Pete’s ranch sat on a main Apache

plunder trail along the Santa Cruz River, five miles north of present-

day Nogales. With the Apache on one side and Sonoran bandits on

the other, the ranch was under siege much of the time. Despite the

danger, Pete and his hired hands raised corn, cabbage, potatoes,

fruits, melons, and hogs on over a thousand acres of rich bottom

land. His hams were famous throughout the southern part of Arizona

and New Mexico.

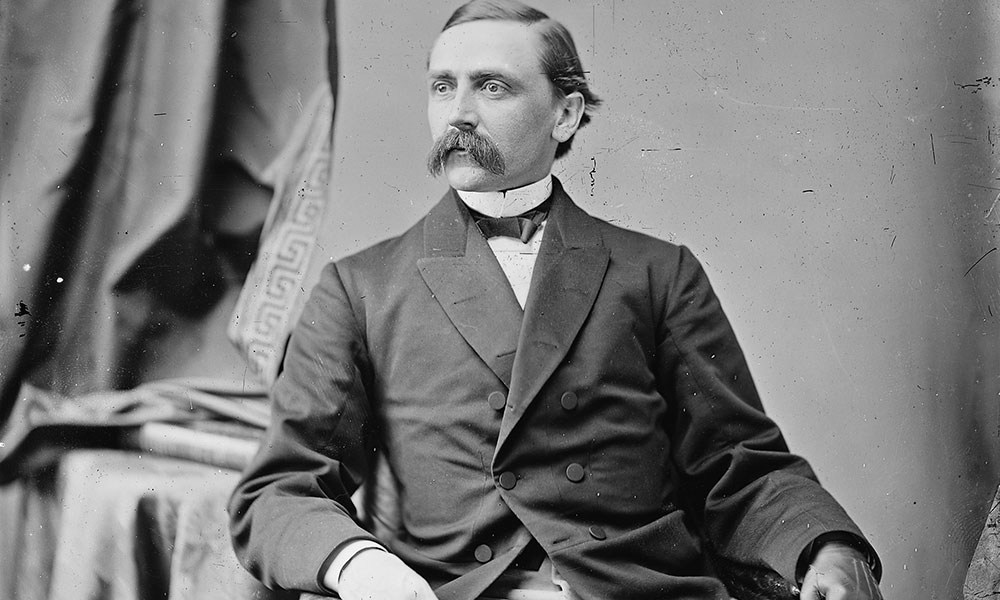

Pete Kitchen was born in Covington, Kentucky in 1822. He

served with the U. S. Mounted Rifles during the Mexican War and

arrived in Tucson in 1854 the same year the Old Pueblo became part

of the United States. During this time Pete became an expert

marksman with a pistol and rifle. He once put a bullet through an

Apache warrior from 600 yards away. His wife Dona Rosa was said to

have been nearly as good with a rifle as he was. When the alarm was

sounded, she would tie up her skirts so they fit like trousers, grab her

rifle and give the Apache a reception as hot as the Mexican chili she

served. Together, they defended their ranch from the banditry and

Apache alike.

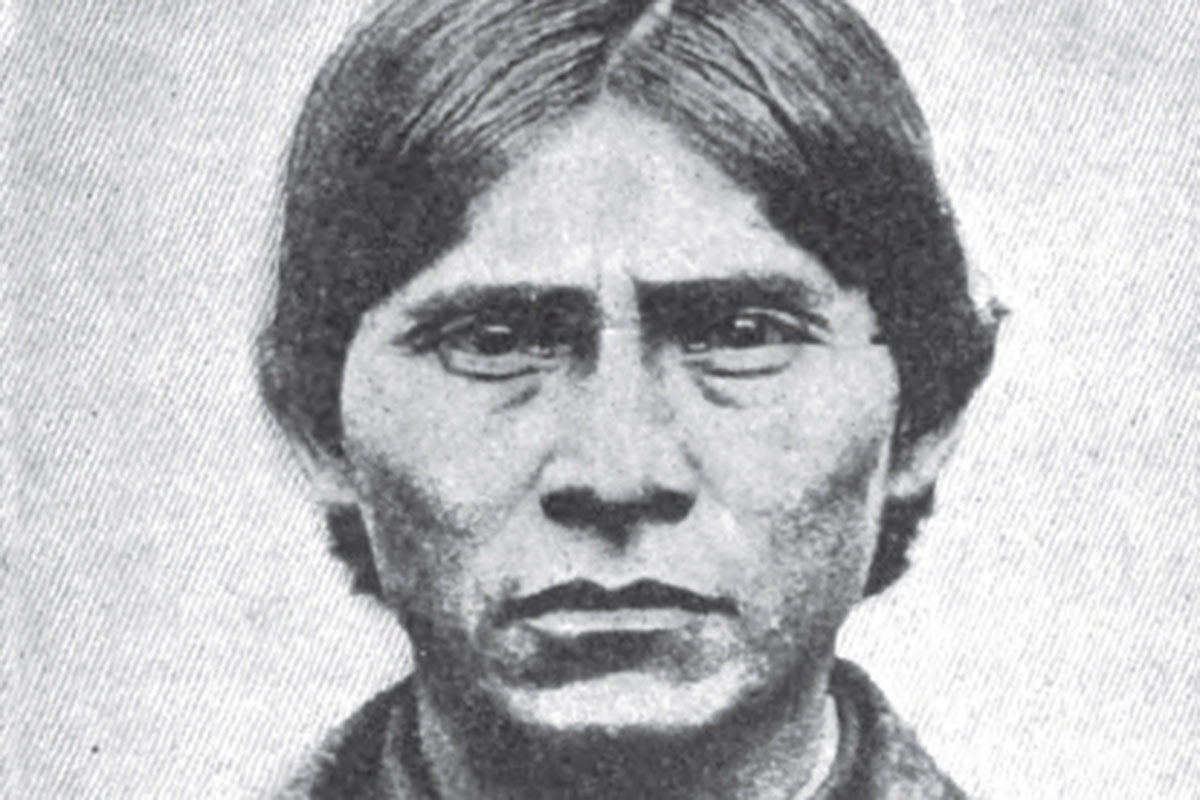

The Apache made many all-out attacks in an attempt to drive

him out. They murdered his young stepson, and killed his foreman.

Several times they tried to burn his house and once they made three

major attacks within a twelve-hour period. All were driven off by Pete,

Rosa and the rest of his sharpshooters from the parapet of his ranch

house. Finally, in frustration and to restore some lost pride they did

something that must have annoyed Pete more than anything else they

could have done. They began shooting arrows into his prize hogs,

turning them into, as one observer noted, “walking pincushions.”

The Apache did everything they could to drive him away but

there he stayed; unconquered and unconquerable. Pete and his

outnumbered outfit stubbornly fought back against their relentless

foe until sometime in 1867 when the Apache decided to alter their

plunder trail and cut a wide circle around his ranch. At length they

came to recognize Pete as an enemy worthy of their respect and a

man better off left alone.

Marshall Trimble is Arizona’s official historian and vice president of the Wild West History Association. His latest book is Arizona Outlaws and Lawmen; The History Press, 2015. If you have a question, write: Ask the Marshall, P.O. Box 8008, Cave Creek, AZ 85327 or email him at marshall.trimble@scottsdalecc.edu.