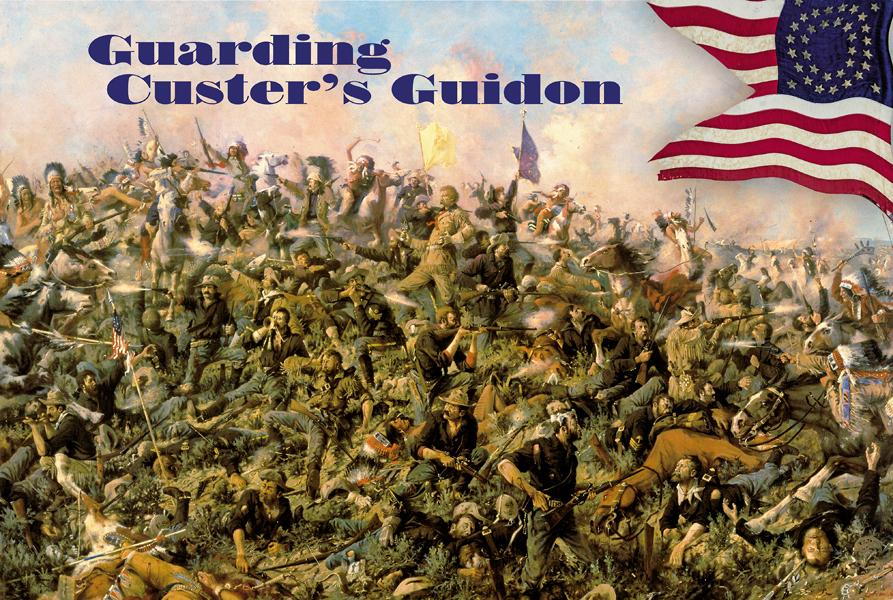

They were all dead; most were stripped of clothing, weapons and gear—including flags. Lieutenant Col. George Armstrong Custer, along with five companies of the 7th Cavalry totaling about 210 men, had been wiped out by the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne along the Little Big Horn River in southeastern Montana.

They were all dead; most were stripped of clothing, weapons and gear—including flags. Lieutenant Col. George Armstrong Custer, along with five companies of the 7th Cavalry totaling about 210 men, had been wiped out by the Lakota and Northern Cheyenne along the Little Big Horn River in southeastern Montana.

On June 25, 1876, Custer had approached this village of thousands of Indians with about 700 men organized into 12 companies. Each company had a swallowtail flag, or guidon, carried by a corporal. These flags served as formation markers and rallying points. They were articles of pride, and during battles, men fought and died to ensure the enemy did not capture their guidons.

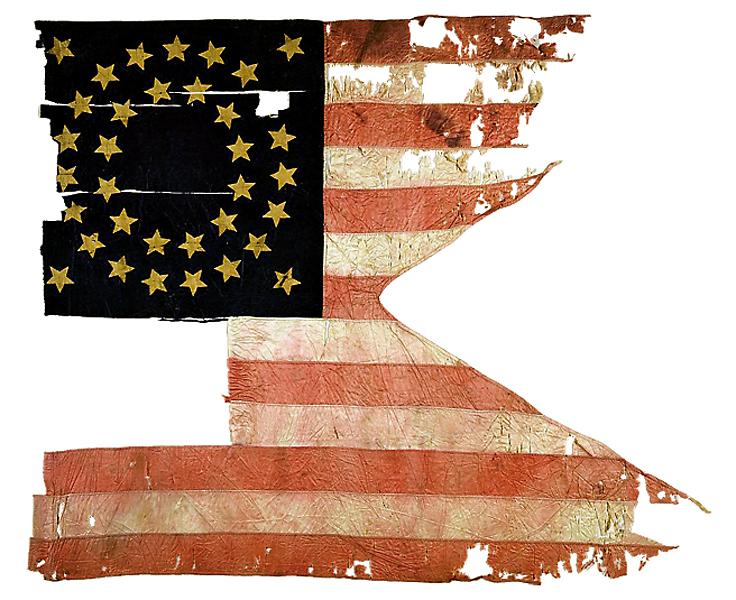

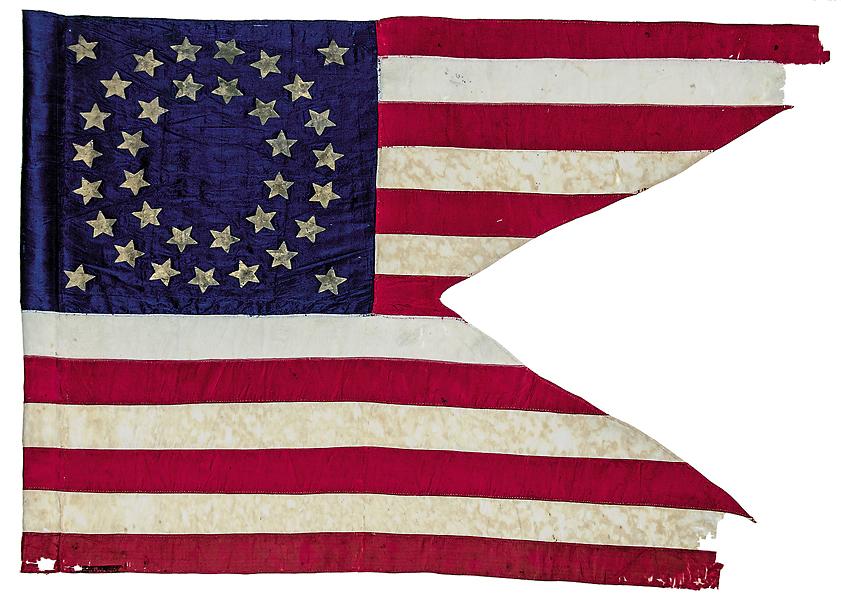

Hand-stitched by New York City seamstresses during the Civil War, these 33-inch-by-27-inch silk flags featured a field of 13 red and white alternating stripes and a blue canton with 35 stenciled gilt stars, forming a circle within a circle, plus four more stars, one in each corner of the canton. At the top of the nine-foot, straight-grained ash lance, a brass spear point finial secured the guidon. None of the guidons had markings to distinguish the companies that possessed them.

The 7th Cavalry’s attack began to unravel after Maj. Marcus Reno halted his charge on the upstream end of the village where the Hunkpapa Lakota were located. He dismounted his men and had them form a skirmish line. Indians maneuvered around the skirmish line, forcing Reno to fall back toward the river. As the fight intensified, Reno lost his nerve and led a retreat; many of his men did not make it.

Two of his companies, A and G, lost their guidons during the retreat, but not Company M. Private Frank Sniffin had torn his company’s guidon from its lance, stuffed it in his shirt and brought it to the top of the bluff where Capt. Thomas French attached it to a propped-up carbine barrel. When the battle was over, the 7th Cavalry had lost seven guidons, but four were recovered, one immediately.

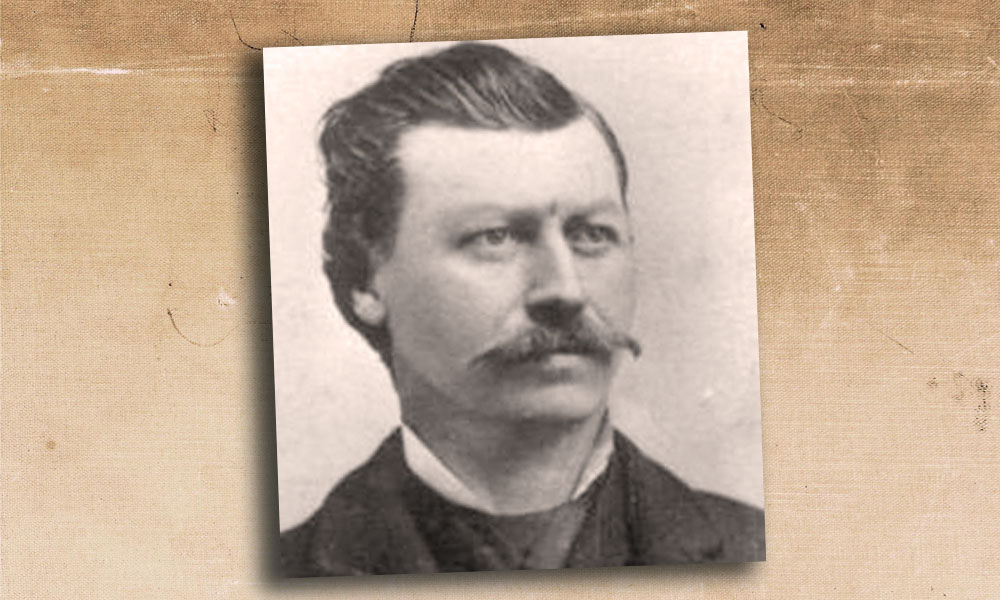

On June 26, Company M 1st Sgt. John Ryan recovered the first guidon at what would be later called Reno Hill. Through the scope of his Sharps rifle, he had seen a mounted warrior waving the guidon to taunt the troops; Ryan shot him off his horse. He rained fire on other warriors who attempted to retrieve the guidon. After dusk, he crawled out and grabbed it, keeping the guidon as his battle souvenir.

In July 1885, Sitting Bull, on tour with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, arrived in Boston, Massachusetts. Ryan was living in nearby Newton. Ryan showed Sitting Bull the bloodstained guidon, and they reminisced about the battle. No known record explains what happened to Ryan’s guidon.

Company A Sgt. Ferdinand Culbertson was among the detail that had buried the dead on Custer’s battlefield. As he turned over the body of Cpl. John Foley of Capt. Tom Custer’s Company C, Culbertson found a guidon Foley had tucked into his shirt. Culbertson’s guidon souvenir found its way to the Detroit Institute of Art. On December 10, 2010, the institute auctioned it for a $1.9 million bid through Sotheby’s New York.

On September 9-10, 1876, at the Battle of Slim Buttes, Brig. Gen. George Crook and his men had recovered a third guidon, known as the Keogh guidon, because they discovered a pair of Company I Capt. Myles Keogh’s gauntlets with it. This guidon is in the possession of the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument in Montana.

On November 25, 1876, Col. Ranald Mackenzie and his troops attacked a Cheyenne village under the leadership of Dull Knife and Little Wolf near the Big Horn Mountains, Wyoming. Troops recovered the fourth guidon; someone had used it to make a pillow stuffed with buffalo hair. This pillow was displayed for many years in the U.S. Army Museum on Governor’s Island, New York. After a transfer to the Smithsonian Institution, it was misplaced. Perhaps a staff person will read this story, rummage around and find it for us all.

Seven guidons were captured or lost, and four recovered, leaving three missing—until now.

While I participated in a June 2012 discussion of Nathaniel Philbrick’s The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Big Horn, hosted by the Old Guys Book Club in Pierre, South Dakota, retired museum director David Hartley asked me if I had heard the South Dakota Cultural Heritage Center Museum had possibly located a guidon from the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

My response was not mild, “What?”

He offered to show me the guidon, making arrangements for us to look at it, preserved in the museum’s climate-controlled storage, several weeks later.

I prepared for my July 3 visit by talking with my friend George Kush, a Canadian Western artist, historian and expert in all things 7th Cavalry. He gave me details to look for in order to determine if this could be a Little Big Horn battle guidon. Kush had provided the write-up on the Culbertson guidon for the Sotheby’s auction.

Inside the museum’s inner sanctum, South Dakota Cultural Heritage Center Museum Director Jay Smith and Collections Curator Dan Brosz led us to a table on which a white display board held a fragile, but in remarkably good shape, swallow-tailed guidon. It had all the features Kush had told me to look for in a genuine Custer-period guidon. I gazed in amazement, thinking, “This is the real deal!”

After the Battle of the Little Big Horn, either an Indian woman or a young Indian boy encamped at Standing Rock Agency in Dakota Territory had given the guidon to Flora Elsie Roach, reported her eldest son, Col. Leon L. Roach. Fearful of white retribution after the battle, Indians were giving away or tossing out items they had acquired at the Little Big Horn. Most Indians associated with the Standing Rock Agency were Hunkpapa Lakota who had received the brunt of the Reno attack on the Little Big Horn village.

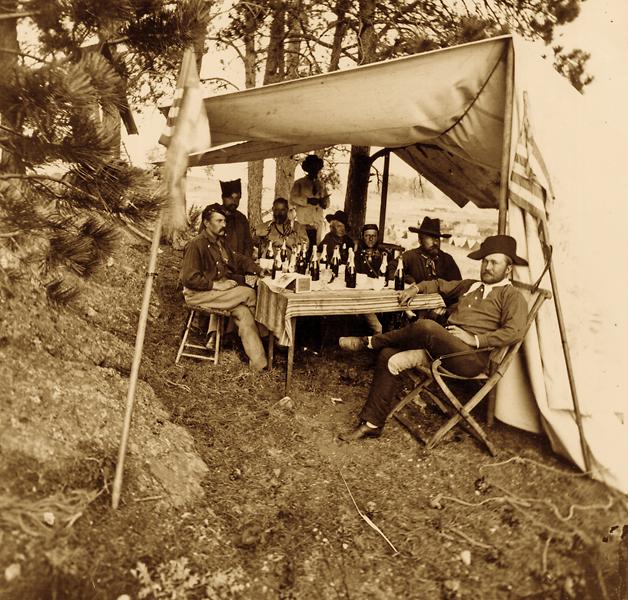

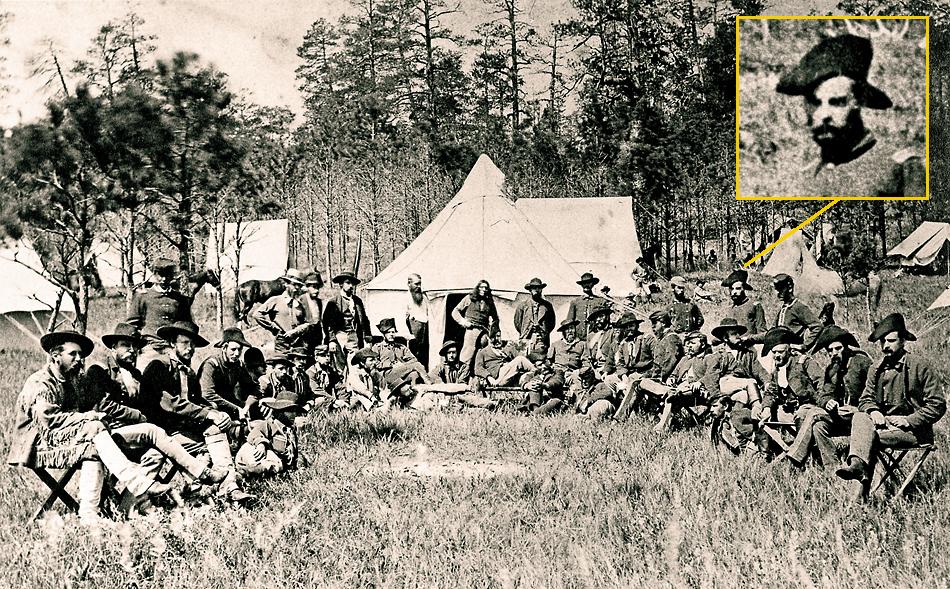

Flora’s husband, 2nd Lt. George Henderson Roach, was stationed with the 17th Infantry at Standing Rock at the time. George had a lifelong career in the Army. He served with the 26th Illinois Infantry during the Civil War; he was with Custer during the 1874 Black Hills expedition that set off the gold rush; and he was stationed at Fort Abraham Lincoln, Dakota Territory. By October 1875, George was stationed at Standing Rock. From April 20-November 22, 1876, George was assigned as commanding officer of a detachment of Indian scouts. He served during the Spanish American War, retiring as a lieutenant colonel. In 1909, George died. He and Flora are buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

George and Flora raised two sons, Leon and Edmund. Leon, who would have been two years old at the time the Lakota gave his mother the guidon, had a lifelong distinguished career in the Army and retired as a colonel. Neither brother had any heirs. On February 3, 1954, Leon sent a letter to the South Dakota Secretary of State indicating he and Edmund wanted to donate their mother’s guidon and other artifacts collected by their father, including a pipe and tobacco pouch Sitting Bull had given George at Fort Abraham Lincoln. On March 11, 1954, the museum received the guidon and other artifacts from Leon. The guidon has been in the care of the South Dakota State Historical Society ever since. For many years, it was encased in glass and displayed in the South Dakota Soldiers and Sailors Museum; it was later removed from display to conserve it.

Brosz and Smith can’t say with absolute certainty that this guidon dates to the battle. “But I tend to think more on the side of that it was there, than it wasn’t,” Brosz says.

“It is compelling to me because Col. Roach did not make any demands about the guidon,” Smith says. “He just wanted to donate it to the historical society. If he wanted to capitalize on it, he certainly could have sold it, and he could have exploited it for notoriety because the story is important. From what evidence I see, the Roachs were an honorable family.”

“What we do know for sure is that it is a 7th Cavalry guidon,” Brosz says. “And we know for a fact a Native American gave it to Flora Roach at Standing Rock shortly after the battle. I think this guidon is the poster child for the importance of preserving things. Fortunately, the Roach family had the foresight to keep the artifact. It is advancing our understanding of our past. History doesn’t open itself up and give us all the answers. A lot of times, it takes some scratching to find the answers that history has hidden away. That is where research and museums come together.”

To nail down the Roach guidon’s authenticity would require the museum staff to cut a small section from the artifact and send it to a lab for DNA, soil, pollen and vegetative composite tests. The staff does not know if the same data is available from past studies of the battlefield site; if not, the tests on the guidon would be inconclusive.

Another complication is that, in 1983, the now-defunct Rocky Mountain Regional Conservation Center in Denver, Colorado, had hand-washed it with deionized water and a mild detergent and stabilized it on archival support. During that conservation effort, the data might have washed away.

One option the staff is considering is for a conservation to conduct a materials study on the twists of thread and weave of silk to determine if that guidon was made by the same New York City seamstresses as other, previously authenticated guidons. Those tests would have to be performed by an independent conservator or lab, with considerable expense involved, and Brosz and Smith confirmed the museum currently has no funds budgeted for that.

“This is an important piece, however,” Smith says, “and we could set up a fund for the project to see if donors are out there who would want to help us fund the authentication project.”

Presently, folks can view a replica of the guidon on display at the museum.

Among 7th Cavalry and frontier history experts, George Kush says he is in the probable camp. “Given all of the evidence, I can’t see why Col. Roach or his sons would lie about the guidon’s origins,” he says. “The colonel knew all of the principals, men such as Custer and Sitting Bull, and had absolutely nothing to gain by invention. Today, authentic historical relics such as these are all about the money, but who in 19th-century America would have ever dreamed that old silk banners might one day fetch over two million dollars at auction? If you had told someone like Sgt. Culbertson that, he’d have declared you insane. To Culbertson, Roach and Ryan, these were hardly more than curiosities. That is why I, a skeptic of the first order, believe that it probably is the genuine article.”

Western artist Jim Hatzell, a former historical interpreter at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, says, “In the history of the Indian Wars, the number of company guidons captured by Lakota or Cheyenne is quite small, making the story look very plausible in my opinion.”

Paul Hedren, a retired National Park Service superintendent and a Great Sioux War historian and author, has seen the Roach guidon and says, “We can probably never know the truth about this flag. But the Hunkpapa presenting it to Flora Roach offered a logical explanation. George Roach had long-term connections with the Hunkpapas, who were certainly well represented in the Custer fight. Thereafter, Roach had no motives for fabricating a story, but only repeated the basic facts as they came to him. So did his sons. This is a piece of the true cross, it seems to me.”

Robert Utley, a 25-year veteran of the U.S. Park Service and an award-winning Western history and 7th Cavalry author, states, “I have to stand with Paul Hedren. What he writes, I subscribe to.”

With so much support, and an increasing desire to fully authenticate this incredible relic of history, the museum set up a donation fund, in March 2013, allocated for further research into the guidon. True West readers may contribute to the project by sending a tax-deductible contribution to: Guidon Project c/o Jay Smith, Museum of the South Dakota State Historical Society 900 Governors Dr. Pierre, SD, 57501.

The museum is considering including the guidon in a future exhibit, but it would be for a limited duration, since artifacts cannot be perpetually on display to ensure they are available for future generations.

One final tantalizing piece of information may still be out there somewhere. In a July 27, 1965, letter Edmund Roach sent to Will Robinson, secretary of the South Dakota State Historical Society, he wrote, “I have a diary kept by my mother which I will reevaluate and see if there is something in it which would be of interest to you and the society.”

My South Dakota contacts scoured archives, libraries and museums for Flora’s diary, with no success. Edmund lived in Los Angeles, so I contacted the Southern California Genealogical Society. The society connected me with distant relatives of Edmund’s wife, but I found no success hearing back from them. Maybe this article will spur further searches for the diary.

Ultimately, given what is known about the guidon today, believing in its authenticity is your decision to make. The Roach guidon is definitively the type used by the 7th Cavalry at the Battle of the Little Big Horn. The Roach family had no known motive, which would doubt the veracity of their story. Did the Roach guidon come from the Little Big Horn battlefield? If not, where did it come from? You get to decide for yourself whether the Roach guidon is the real deal, a true relic from the Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Bill Markley, who rode Custer’s trail from Crow’s Nest to Medicine Tail Coulee and survived the filming of Son of the Morning Star, acknowledges all the folks who contributed to this story. Without them, and especially the unnamed Hunkpapa and the Roach family, this story would not exist.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Sotheby’s New York –

– True West Archives –

– (Detail) Courtesy Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming, U.S.A.; Museum Purchase, 19.69 –>/i>

– Courtesy Museum of the South Dakota State Historical Society, Pierre SD –

– Courtesy Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument –

– Courtesy Robert Utley –