“Remington, Russell and Leigh were once as familiar to the art world as Bach, Beethoven and Brahms to musicians, or Tinker, Evers and Chance to baseball fans.”

That’s how a newspaper from William Robinson Leigh’s home state of West Virginia, the Parkersburg Sentinel, celebrated the artist on May 1, 1954.

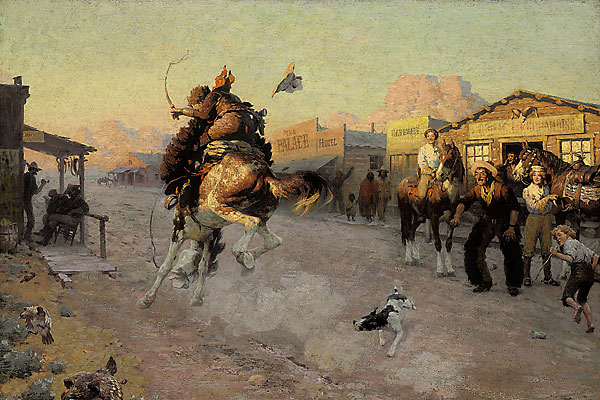

On May 20, 2010, Christie’s New York celebrated him via dollar signs—$800,000 to be exact—when his painting Embarrassed (Range Pony in Town) earned him his highest auction record to date. On the reverse is inscribed “scene from Cody, Wyoming,” a state he toured on hunting trips, beginning in 1910.

On the first trip, the artist’s palate yearned to taste food other than trout, sage hen and squirrel, which Leigh noted in his Wyoming diary, dated July 12 to August 4, 1910. When it came to his palette, he wrote that he could not sketch on an overcast day, because it distorted the coloration, and that a sudden downpour could ruin weeks of work sketching the wilderness region of the Carter Mountain, along the South Fork of the Shoshone River and southwest of Cody.

Leigh’s constant companion during these trips was not only Will Richard, who co-owned the American Taxidermy Shop in Cody, but also bloodsucking flies. “After a day of sketching, my palette was thickly strewn with dead, dying, or famished insects; I ignored them,” he recorded in his autobiography. “After work it took me an hour, with the point of a penknife blade, to pick the dead mosquitoes off my studies.”

In 1913, the famous Yellowstone landscape artist Thomas Moran would give kudos to Leigh for drawing out in the field: “He’s no parlor car artist.”

Yet it’s true that in the French post-impressionist era, this artist who had trained in Munich realism was not a favorite of the art critics, who often dismissed him as a romantic illustrator, not a true artist. The Washington Sun Star actually put it the nicest, when the newspaper reported on January 14, 1917, on Leigh’s lack of free expression: “Sharp, Russell, Remington, Schreyvogel, Paxon, DeCamp, even Goodwin are not as capable as Leigh, but they grabbed it.”

Toward the end of his life, though, Leigh had his fans. “His principal admirers are not critics, but western enthusiasts and anthropologists. They like his photographic realism and painstaking authenticity,” Newsweek reported on January 24, 1944.

He would finally gain the right to sign his name with an “N.A.” in exhibition catalogues when he was elected a National Academician on March 2, 1955. Yet that title would appear only posthumously, as he died at the age of 88, nine days later, with an unfinished painting left on his easel.

Leigh is most famous for his portrayals of the Southwestern Indian, who often appears alone to emphasize Leigh’s admiration of the Indian’s individualism and close affinity to nature. Land of His Fathers, depicting a Navajo boy solitarily perched over the goat herd he commands, exemplifies this well; it hammered in at Heritage Auction Galleries in Dallas, Texas, on May 15, 2010, for $11,000.

Like Leigh told the Dallas Morning News on January 20, 1946, the “only good Indian in art is a big one.”