John D. Lee VS. A Firing Squad

“Center My Heart Boys!!”

March 28, 1877

The execution of John D. Lee was supposed to be a secret, but as Marshal William Nelson and U.S. Attorney Sumner Howard loaded their prisoner into a closed carriage and drove south from the jail at Beaver, Utah, at least 20 citizens followed the carriage because Howard had alerted the press. A separate group—about 20 soldiers under Lt. George Patterson—left Fort Cameron and waited for the carriage at Leach Spring, and shortly before dawn, the two groups met and travelled on together to Mountain Meadows, arriving at 9:30 p.m. John D. Lee slept soundly in the carriage, and in fact, his snoring kept several others awake. At dawn on March 28, the officers deployed pickets in the surrounding hills and drew three wagons in a semicircle about 100 yards east of the location of Colonel Carleton’s cairn. When Lee awakened, he got out of the carriage, wearing a red flannel shirt and sack coat. He partook of a hearty breakfast and a cup of coffee. He told the assembled reporters he had not been on this ground since 1857. As the word spread, the crowd of civilians grew to about 75, most of them eager to see the morbid spectacle. Contrary to later reports, none of Lee’s relatives were present. After the coffin was built and placed in position, Lee walked over to it and sat down.

Note the bemused grin. The guy had sand. The authorities parked three wagons in a semicircle, then hung blankets between the wagons to create a blind from which the firing squad would stand in the center and shoot the guilty party. For his part, John D. Lee sat on a coffin of rough pine boards (built on the spot with wood hauled out to the site in a wagon). Lee sat on the coffin facing his executioners. They were reportedly armed with nonmilitary Springfield “needle guns.” After a prayer by a Methodist minister, Marshal William Nelson put a blindfold on Lee. When the time came, eyewitnesses said Lee raised both hands above his head and reportedly said, “Center my heart, boys!” At exactly 11:00 a.m. Nelson gave the order, “Ready, aim, fire!” and a “line of flame shot out from the wagons.” There was no moan or yell; John D. Lee simply fell quietly into his coffin, his feet still resting on the ground.

A Recipe for Disaster

On January 1, 1856 Brigham Young appointed John D. Lee “Farmer to the Indians.” In this capacity Lee was a federal government agent and it was his job to protect the Southern Paiutes and emigrants from each other and to teach them to farm. Lee was paid a $600 annual salary, paid in gold, which was a fortune in that time and place. There were also rumors that the Mormons were arming their Paiute allies. Lt. Sylvester Mowry of the U.S. Army claimed they were “all armed with good rifles. Two years ago they were armed with nothing but bows and arrows of the poorest description.”

Author Will Bagley makes the claim, “The Mormons came to regard the Indians as a weapon God had placed in their hands.” And that the Indians would help to fulfill Joseph Smith’s Laminate prophecies, and “avenge the blood of the prophets.” Patriarch Elisha H. Groves prophesied as he blessed Col. William Dame in 1854, “The angel of vengeance shall be with thee.” Many of the Southern Utah Saints believed the war at the end of time had already begun and the Saints believed the Indians were a weapon God had placed in their hands.

As the conflict between the U.S. government and Mormons increased, so did harassment of travelers. Into this cauldron of resentment the Fancher wagon train proceeded tragically. Add to that the belief in blood atonement, and you have a recipe for the slaughter that followed.

The Southern Utah Saints saw themselves as Old Testament people. As one of them, Jedediah Grant, put it, “We would not kill a man, of course, unless we killed him to save him.”

Add to all of this, the brutal assassination of Mormon apostle Parley Platt in Arkansas at the hands of a vengeful husband, which did nothing to endear the Saints toward wagon trains from Arkansas traveling through their region.

U.S. Army sharpshooters stood in the enclosure of three wagons parked in a U-shaped semicircle. Tarps were wrapped around the wagons and the exposed corners to help conceal the shooters’ identities. Sitting on his coffin, Lee had a hood placed over his head, and he raised his arms high and said, “Center my heart, boys.” After the command of “Ready. Aim. Fire!” the shooters did just that, and Lee fell backwards into his coffin.

–All Images Courtesy True West Archives

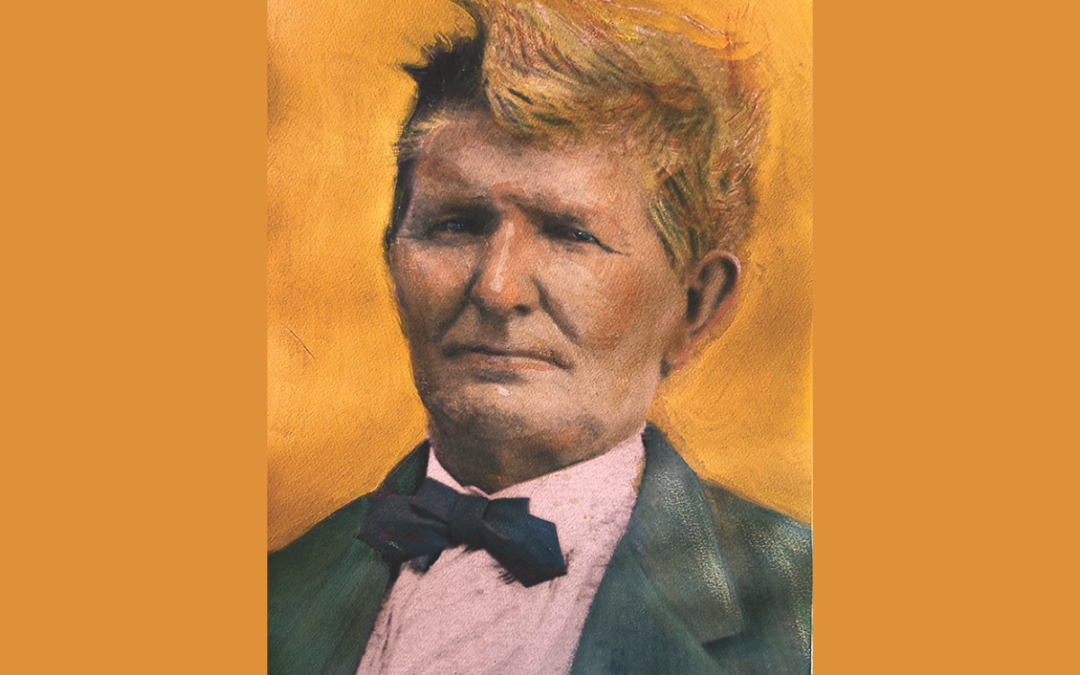

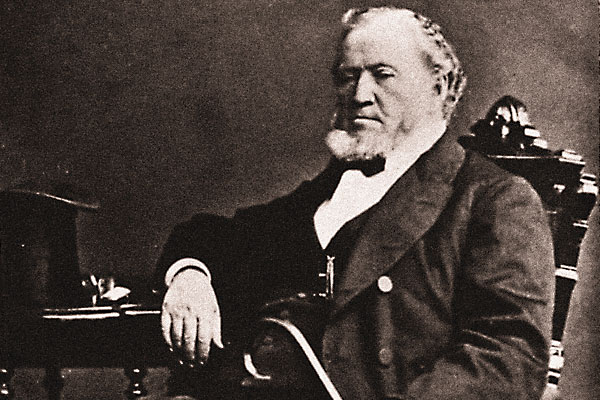

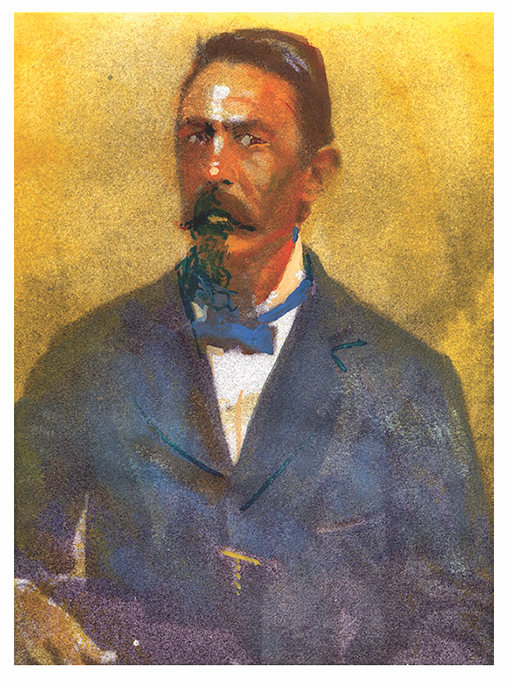

A photograph of John D. Lee looking at the camera moments before his execution. After the exposure was taken, Lee reportedly called the photographer over and asked him to be sure and send a couple prints to his “two favorite wives.” Of all his many wives, only Caroline, Emma and Rachel stayed with him to the end, so it’s interesting that out of the trio, he still had two favorites.

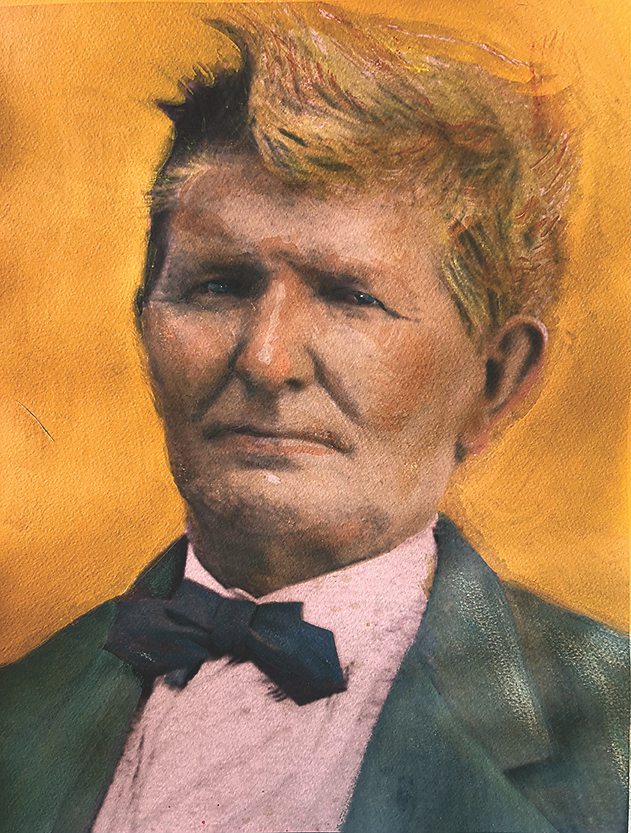

The Gawkers – Note the wagon tongue at right which is part of one of the wagons used to conceal the shooters.Back to Mountain Meadows After the second trial and several appeals on behalf of Mr. Lee, the U.S. government finally got a guilty verdict, and it was decreed that the alleged ringleader of the Mountain Meadows disaster should be driven to that exact meadow and shot to death by a firing squad. It was supposed to be a secret, but one of the attorneys alerted the press, and you know how that goes: everyone has one person they can trust, so the next day as the U.S. troops and their prisoner arrived at the execution site, so did 75 or so gawkers.

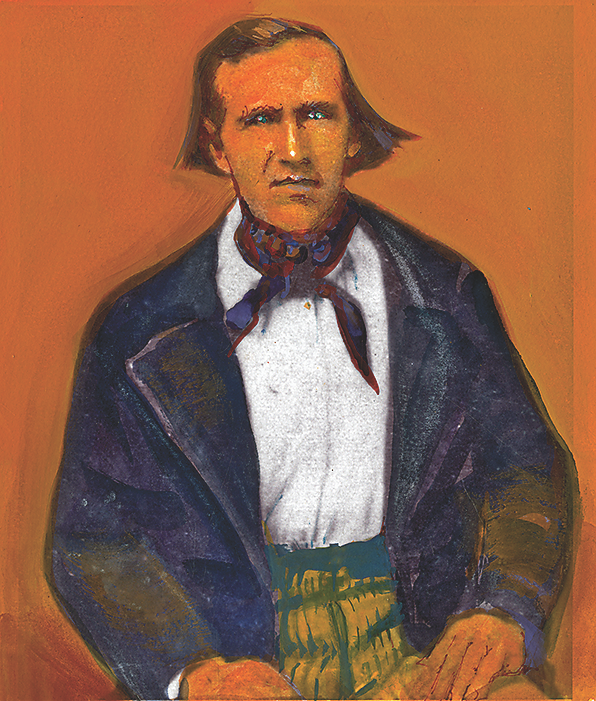

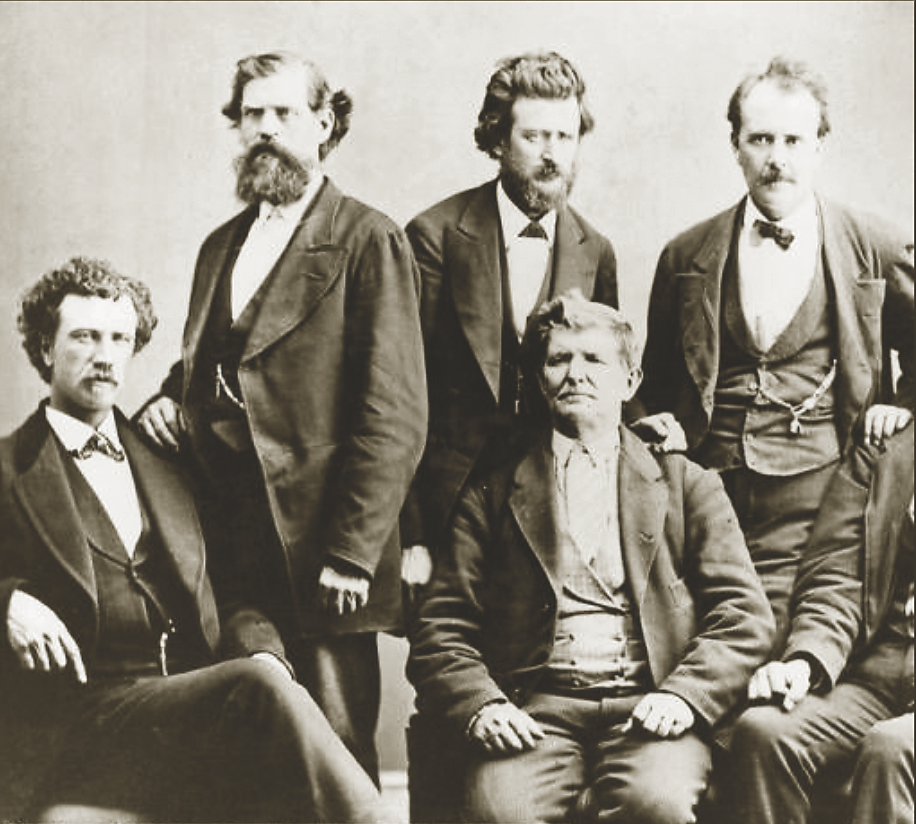

One Final Irony It’s the old Gypsy curse: may you be found among lawyers! John D. Lee, seated at right, with his legal team, including Wells Spicer over Lee’s left shoulder. Spicer, of course, would find himself at another legal circus, I mean hearing, in Tombstone, A.T. in November of 1881 presiding over the Fremont Street Fight, later to be made famous as the Gunfight at the O.K. Corral.

Guilty as Sin

A short list of what happened to the remaining Mountain Meadows co-conspirators who were known derisively as “The Mountain Meadows Dogs.” This notorious pack included Lee, Haight, Higbee and Stewart, among others.

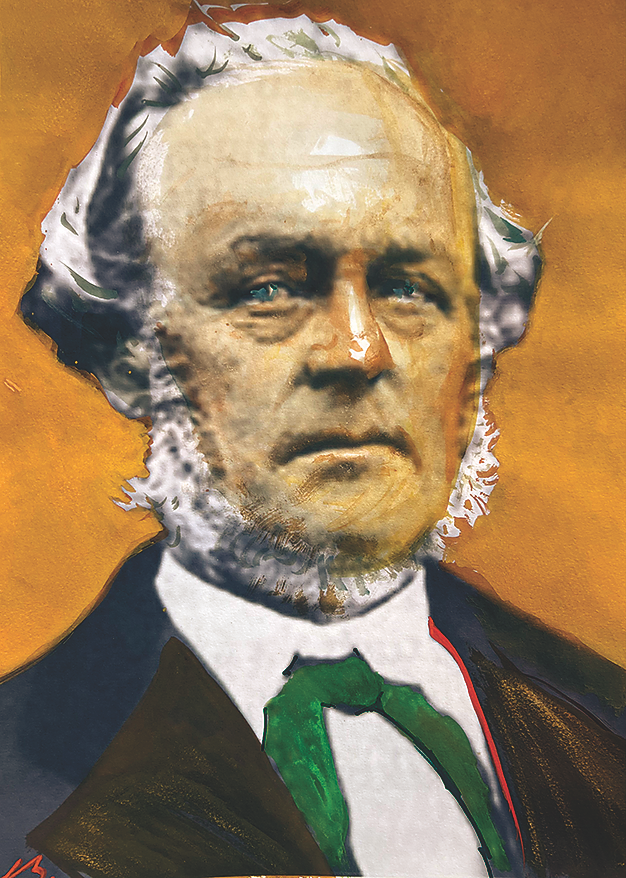

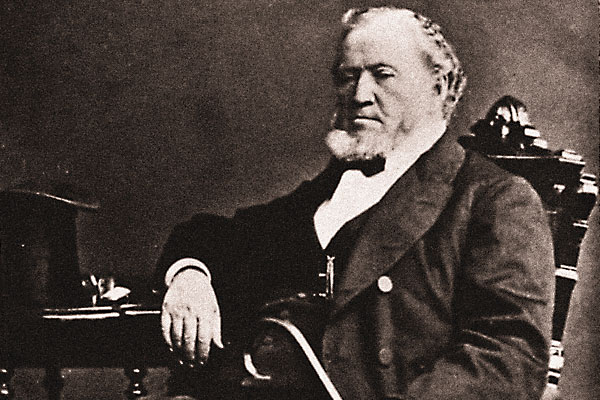

Issac Haight

Haight fled Utah under the alias of “Horton” and wandered between the LDS settlements in Arizona, Colorado and Mexico and died as a member in good standing in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Thatcher, Arizona, in 1904.

John B. Higbee

John B. Higbee

The field commander at Mountain Meadows, John Higbee, saw his career blossom after the massacre and was elected mayor of Cedar City from 1867 to 1871. Brigham Young appointed Higbee president of the town’s United Order in 1874. After Lee’s arrest in 1874, Higbee went into hiding. Using the alias “Bull Valley Snort,” Higbee wrote a document for his family, giving his version of the massacre in February 1894. At the end of his self-serving excuses—his basic claim is “the Indians made us do it”—Higbee said the massacre had left him “damned, his family scattered, some dead, others grown up and strangers to him.” He died in Cedar City in December of 1904. “It seems Somebody has contracted a Great debt.”

Colonel William H. Dame

Col. William H. Dame was the mayor of Parowan, Utah, and he controlled the military in Iron County. He was also a stake president of the LDS church in Parowan. Although he was arrested and spent time in jail for his role, Dame was subsequently acquitted of his charges—the prosecutor dropped charges against Dame as part of a deal to convict Lee—and Dame went on to hold other offices. At the end of his life, Dame refused to clear Brigham Young and died of paralysis, actually a second stroke, in 1884. He was 64.

Jacob Hamblin

Jacob Hamblin was in Salt Lake City meeting with Brigham Young at the time of the massacre, and Young allegedly instructed Hamblin about the Paiutes, that they “must learn to help us, or the United States will kill us both.” Hamblin was away when the massacred happened, but he met John D. Lee on the trail and Lee admitted his roles in the killings. After the massacre, the surviving children were initially taken to Hamblin’s ranch, and three of them resided there for the next two years. A year after the massacre, Hamblin went on a mission to the Hopi Mesas in Arizona, where he took a Hopi wife. (He eventually had four wives and would father 24 children.) Hamblin also advised John Wesley Powell’s second expedition into the Grand Canyon. Following the Edmunds Act of 1882, an arrest warrant was issued for Hamblin for practicing polygamy. From then on, he continually moved to avoid arrest, moving from Arizona to New Mexico and then Chihuahua, Mexico, where he died on August 31, 1886.

Philip Klingonsmith

Klingonsmith was kicked in the head by a horse and soon after lost his position as leader of the LDS church in Cedar City. After fleeing to Nevada, he confessed his involvement at Mountain Meadows and named names. Afterward, he was forever fearful of being assassinated. Rumor says he died in either Nevada or Mexico.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Lee’s body was transported north to Paragonah, and then on to Panguitch, Utah. It was a two-day trip and the body was so decomposed the family put his temple clothes over his corpse and buried it in the local cemetery. Local tradition is that the family feared grave robbers, so they reburied Lee in the basement of Caroline Lee’s home.

Rumors almost immediately circulated claiming that Lee was not killed by the firing squad and that they used blanks and allowed him to escape. Some versions of these rumors exist to this day, claiming he made his way to Mexico and lived out his days there.

John D. Lee had 19 wives and 56 children, and they sure ran up the scorecard on civil servant achievement. One of his descendants became Senator Mike Lee of Utah, and another became a Utah Supreme Court justice, Thomas R. Lee. Another descendant, Gordon H. Smith was a U.S. senator from Oregon. Then we get U.S. representative Mo Udall and Stewart Udall from Arizona, and their respective sons, Senator Mark Udall and Tom Udall from Colorado and Senator Tom Udall from New Mexico.

Perhaps due to the incredible political clout of the above mentioned offspring, John D. Lee was reinstated into the church membership and temple blessings on April 20, 1961. He had been excommunicated in October 1870 for his involvement in the Mountain Meadows Massacre and the only participant who had been banned.

Recommended: Blood of The Prophets: Brigham Young and The Massacre at Mountain Meadows by Will Bagley.