Pack it up, round ’em up and drive north for an Old West adventure.

Sherman, Texas, native S.H. Woods was 16 years old when he was “second boss—the horse rustler”—on a cattle drive in 1881.

Although the drive had started along the Chisholm Trail in the Chickasaw Nation, the herd had moved onto the Western Trail, and Dodge City, Kansas, was just eight or 10 miles ahead when a nighttime storm blew in.

“Talk about thunder and lightning!” Woods recalled in The Trail Drivers of Texas, the Old Time Trail Drivers’ Association’s mammoth 1924 collection of reminiscences compiled and edited by J. Marvin Hunter. “There is where you could see phosphorescence (fox fire) on our horse’s ears and smell sulphur. We saw the storm approaching and every man, including the rustler, was out on duty. About 10 o’clock at night we were greeted with a terribly loud clap of thunder and a flash of lightning which killed one of our lead steers just behind me. That started the ball rolling. Between the rumbling, roaring and rattling of hoofs, horns, thunder and lightning, it made an old cow-puncher long for headquarters or to be in his line camp in some dug-out on the banks of some little stream.”

And it didn’t end there, Woods said, because “just as soon as we could get them quiet, some other herd would run into us and give us a fresh start. Finally, so many herds had run together that it was impossible to tell our cattle from others. When lightning flashed, we could see thousands of cattle and hundreds of men all over the prairie, so we turned everything loose and waited patiently for daybreak.”

It took about a week for trail crews to separate the herds. Those who were driving to Dodge City hadn’t far to go. But Woods and his pards were bound for Wyoming. Which meant they had to cross the Arkansas River “just above Dodge City,” and move through northwestern Kansas and into Nebraska, where they followed the North Platte from Ogallala to Forts Laramie and Fetterman in Wyoming. When they left the Platte, they crossed 60 waterless miles in four days. In all, Woods recalled, “It took us just exactly three months and twenty days to drive a herd of Southern ‘doggies’ from the Red River and deliver them at the Wyoming ranch.”

The gist of this story being: The Western Trail was not for sissies. Maybe that’s why you hear a lot more songs sung about the Chisholm and Goodnight-Loving trails—not that those trails were rides in the park for Texas cowboys.

Various routes

One major difference between the Chisholm Trail—meaning the Texas-to-Kansas cattle trail and not the Oklahoma-to-Kansas path named after trader Jesse Chisholm—and its forerunner, the (Texas-to-Missouri) Shawnee Trail, was that the Western Trail did more than send cattle to packing houses.

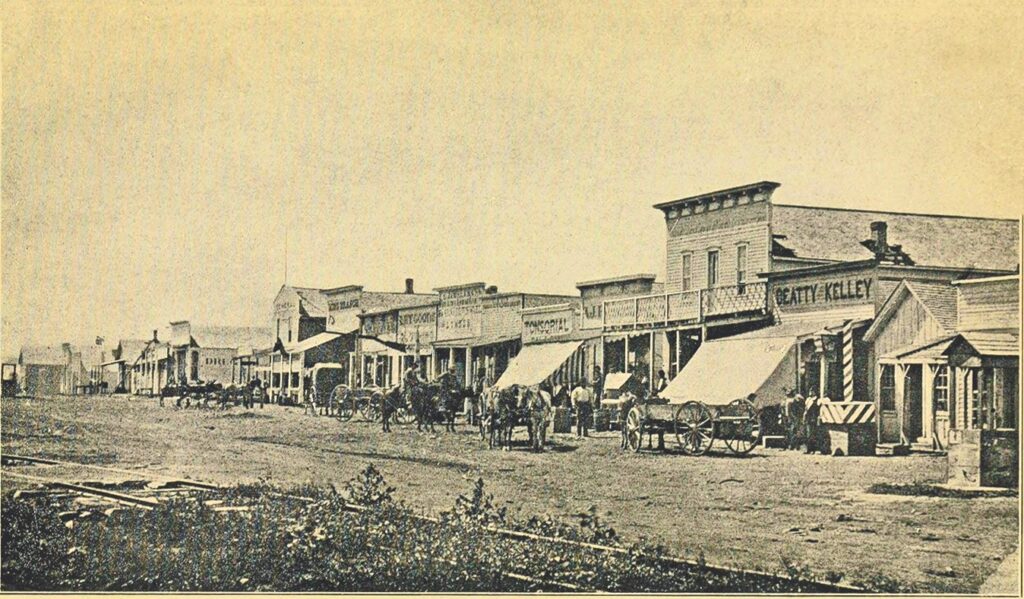

Sure, Western Trail cowhands brought cattle to railroad shipping points like Dodge City (Boot Hill Museum) and Ogallala (Boot Hill Cemetery) to feed millions of people, but it was also used to stock ranges in Wyoming, Montana and the Dakotas.

When Kansas quarantine laws (to prevent the spread of a “Texas Fever,” often fatal to Kansas cattle) spread westward, more Chisholm Trail drovers began using the Western Trail.

Most trail historians credit John T. Lytle for blazing the Western Trail, later also called “the old Fort Griffin and Fort Dodge trail,” when he drove a herd from southern Texas to the Red Cloud Agency, then located near western Nebraska’s Fort Robinson, in 1874.

The trail began in Bandera County—where Hunter founded Frontier Times Museum (still around!) in the town of Bandera in 1927. The trail basically went through Kerrville (Museum of Western Art), to near Menard, and on to Albany, Fort Griffin (Fort Griffin State Historic Site) and Vernon (Red River Valley Museum) and finally on to Doan’s trading post, established in 1878 by Jonathan Doan and his nephew Corwin F. Doan. Near there, the herds swam the Red River into present-day Oklahoma.

With herds usually numbering around 2,000 to 2,500 cattle, the route taken depended on grass, so the routes varied.

Two routes today—U.S. Highway 183 and State Highway 34—promote the Western Trail, which passed through Fort Supply before crossing into Kansas. Elsewhere, trails split, or trail bosses had options. They might take the Ghost Trail, also known as the Quanah Detour, from present-day Quanah, Texas (Quanah, Acme & Pacific Depot Museum) to the Salt Fork of the Red River near Mangum, Oklahoma (Old Greer County Museum & Hall of Fame). Or they could follow the Mobeetie Trail to Mobeetie (Mobeetie Jail Museum) in the Texas Panhandle.

No matter where they went, it was rarely easy.

In 1882, F.M. Polk, who had been driving cattle for a decade, hired on for a drive in which he had “plenty of bad horses to ride” and “stampedes were so numerous that I could not keep track of them. …There was so much rain, and the cattle were so restless, we never knew what to expect. Lots of times I never pulled off my boots for three days and nights.”

Trail’s End

The Kansas Legislature prohibited all Texas cattle from entering the state in 1885, but Texas cattle drovers soon learned they weren’t just upsetting Kansans. In 1886, the Austin Daily Statesman reported: “There has been some talk of holding an indignation meeting to protest against the late action of the Panhandle free-grass syndicates, in refusing to let south Texas cattle go up the Western trail.”

So, the Western Trail, having sent an estimated six million to seven million cattle north, faded out like the Shawnee, Chisholm and even the Goodnight-Loving.

F.M. Polk wasn’t sad to see it go. Left in Mobeetie in 1882 because of a quarantine, “the boss and I had a row,” so Polk rode out for Dodge City and bought a one-way train ticket.

“On my way home,” Polk recalled in The Trail Drivers of Texas, “I reviewed my past life as a cowboy from every angle and came to the conclusion that about all I had gained was experience, and I could not turn that into cash, so I decided I had enough of it, and made up my mind to go home, get married and settle down to farming.”

A Wide Spot in the Road

NATIONAL HISTORIC TRAILS INTERPRETIVE CENTER

Founded in 2002 in Casper, Wyoming, the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center isn’t about cattle drives but those early interstates of 19th-century Western America—primarily, the Mormon, Oregon, California and Pony Express trails—and the estimated half a million emigrants who traveled west between 1840 and 1869 and the Pony Express riders who delivered the mail.

In addition to galleries focusing on the individual trails, the nonprofit museum also shows visitors “Ways of the People,” “The U.S. Looks West” and “Epilogue: The Trail Today.” And while the focus is on history, this interactive museum is high-tech, from the short introductory film Footsteps to the West, a 2003 Spur Award finalist for Best Documentary Script by Candy Moulton and Dan Gagliasso, to virtual rides in a stagecoach and wagons. You can even push a Mormon handcart. nhtcf.org

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: Brick’s River Café, Bandera, TX; Lytle Land & Cattle Company, Abilene, TX; Prime on The Nine, Dodge City, KS; Plains Trading Post Restaurant, Douglas, WY

Good Lodging: Y.O. Ranch Hotel & Conference Center, Kerrville, TX;

The Outside Inn, Magnum, OK;

Fort Robinson State Park, Crawford, NE; C’mon Inn Hotel & Suites, Casper, WY