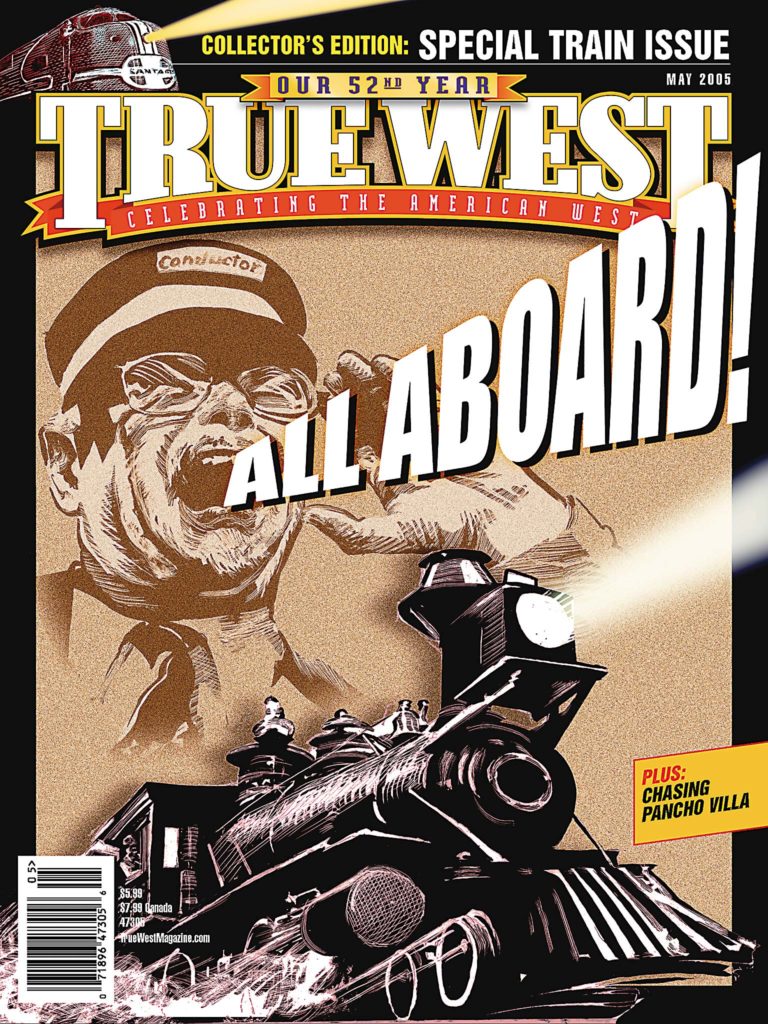

Speed across the plains behind the world’s largest steam locomotive to the legendary Cheyenne Frontier Days Rodeo and relive a Western tradition sparkling with nostalgia and style.

Speed across the plains behind the world’s largest steam locomotive to the legendary Cheyenne Frontier Days Rodeo and relive a Western tradition sparkling with nostalgia and style.

With a little advance planning, you too can join hundreds of rodeo fans who embark from Denver, Colorado’s historic Union Station every summer and head north for a day of nonstop action and fun.

Frontier Days Rodeo was conceived in 1897 by Frederick Angier, a passenger agent for the Union Pacific Railway. He hoped to create an annual event in Cheyenne, Wyoming, to showcase roping and riding skills, and to celebrate the life of the American cowboy. If local ranch hands would put on a rodeo, Angier believed the Union Pacific could deliver the spectators. With the assistance of local businessmen, the dream was realized, and the first Cheyenne Rodeo was held in September of that same year. Because there was no arena, merely a pasture and a grandstand, spectators held the livestock at bay by encircling the grounds and raising opened umbrellas to turn back runaway broncs.

The event was an immediate hit and commanded much traffic for the Union Pacific passenger department. As a sponsor, the Union Pacific also became a major contributor of awards for the many cowboy contests.

By 1908, Frederick Bonfils and H.H. Tammen, owners of the Denver Post, sensed a marketing opportunity for the Denver paper. As sponsors, they helped publicize an already wildly popular sport. The excursion became a social event that continued into mid-century, with time out for WWII.

In 1946, Editor Palmer Hoyt and his promotions manager Alexis McKinney put the Post train back on Track One. This time, the ride was filled by invitation only and was an all male affair, with everyone in mandatory Western attire. Wealthy and prominent guests clad in their best 10-gallon finery included the famed “hell for leather” Vice Presidential candidate Lyndon B. Johnson. The train ran until 1971, when Amtrak took over passenger service from the Union Pacific, quietly relegating the Post train to the annals of railroad history. In 1992, however, the Rio Grande (a subsidiary of the Union Pacific) started the train up again.

Back in the late 1800s, this gala spectacle included several coaches pulled by a steam locomotive billowing clouds of steam and gray smoke into the air. Massive flanged wheels bore the many cars, and the whole affair arrived and departed to the sound of an ear splitting “steamboat” whistle that could be heard for miles.

The duration of the ride, then as now, was a 100-mile journey that took three hours and traversed northward through the rugged hills and prairie lands of the Colorado-Wyoming border. Passengers enjoyed open country dotted with buffalo and antelope, and nearer to Cheyenne and Denver, vistas of well-ordered ranches and farms with tidy homesteads. The track, for the most part, was a virtual tangent between Denver and Cheyenne, following U.S. Highway 85 through Denver, Commerce City, Brighton, Fort Lupton, La Salle, Greeley, Eaton and Ault before crossing the Wyoming border and winding into Cheyenne.

Today, riding the Denver Post Frontier Days Train is a favored event, requiring advance res-ervations by the faithful who consider it a Frontier Day ritual. The train is usually pulled by Union Pacific’s No. 3985 (a.k.a. the Challenger), a 122-foot, steam-driven engine with an articulated (hinged) frame that allows the train to negotiate curves. It weighs over a million pounds, has six-foot diameter drive wheels and is often throttled between 60-70 miles per hour. The Challenger was built in 1943 during WWII to haul freight and answer the huge demand for transportation. Once part of a whole class of locomotives (105 in all), it’s now one of only two remaining steam locomotives still operated by the Union Pacific. The Challenger was retired in 1959, but in 1981, it was reconditioned for operating use. When not on the rails, it resides in Cheyenne.

The train’s comfortable orange and yellow coaches include regular dome and premiere seating, dining cars and even a dance car with live music. Sixteen passenger cars—some rescued from other passenger lines from the 1950-60s and merged into what is now considered the world’s largest railroad—have colorful names, such as the City of Salina, the Sunshine Special and the Portland Rose. And since steam actually falters on occasion, the train also boasts a “backup” locomotive—a diesel of the 6900 or Centennial class (the largest diesel engine ever built)—as well as an extra tender (coal car), containing the most important commodity—water.

Privileged passengers can buy a ticket for the July 23 rail tour in advance;

tickets become available in May. Departure is at 7:00 a.m. in order to arrive at Cheyenne’s historic station with its landmark distinctive clock tower around 9:45. From there, viewers can watch the opening parade.

They’re then transported by bus to the rodeo grounds for a barbecue lunch accompanied by a Country Western serenade. After lunch, it’s on to the grandstands to witness the afternoon rodeo in what has become the grandest spectacle in the modern-day West: “Frontier Days, the Daddy of ’em All.”

By 4:30 p.m., it’s back at the station for a 5:30 departure and a romantic ride home on what may be the grandest train ever to cross the prairies.

Eric Ibbotson is a lifelong rail fan and Denver native. He has traveled thousands of rail miles and is active in Colorado’s Rocky Mountain Railroad Club, National Railway Historical Society’s Intermountain Chapter and Rock Island Technical Society, for which he edits the Colorado Chapter newsletter.

Photo Gallery

– By Eric Ibbotson –