Gettin’ along little dogies up the Western Trail is still a fun road trip today.

By the 1880s, time was catching up with the Western Trail—the cattle-drive highway from Texas to Kansas/Nebraska/Dakotas/Colorado/Wyoming/Montana. Just as time—and angry farmers and stock raisers—had caught up with the Shawnee and Chisholm trails before.

It’s easy to blame “Texas Fever,” the tick-spread disease that proved fatal to domesticated cattle along the trail’s path (Texas longhorns were immune), for the closing of the trail. But Kansas sodbusters weren’t entirely to blame.

Texas cattleman J.G. Reed told a Kansas City Times reporter in 1881:

“Well, sir, the fact is there is a market for cattle in Texas, and it don’t pay to drive them up north. Besides, there are not as many cattle in the State as there used to be. The ranges are becoming circumscribed, and settlers are being brought in by the railroads, especially in northern Texas, and they are taking up land for farming purposes that used to be devoted to stock ranging.”

Reed estimated about 180,000 would hit the markets that year, “though some claim that 200,000 are on the drive.”

Claim? Was Reed suggesting that a Texan might exaggerate?

He wasn’t alone. Five years earlier, Mines, Metals and Arts reported: “It is known by actual account that the 55,000 head of cattle reported to have passed up the western trail [in 1876], does not exceed 35,000.”

Sight-seeing

John Lytle gets credit for blazing what eventually replaced, and topped, the Chisholm Trail. In 1874, Lytle brought 3,500 longhorns from southern Texas to the Red Cloud Agency at Fort Robinson, Nebraska.

The Western Trail started with feeder trails that headed from cattlemen’s gathering areas to San Antonio (Briscoe Western Art Museum, The Buckhorn Saloon & Museum and Texas Ranger Museum) and Bandera (Frontier Times Museum, Western Trail Heritage Park). From there it kept west of the old Chisholm Trail.

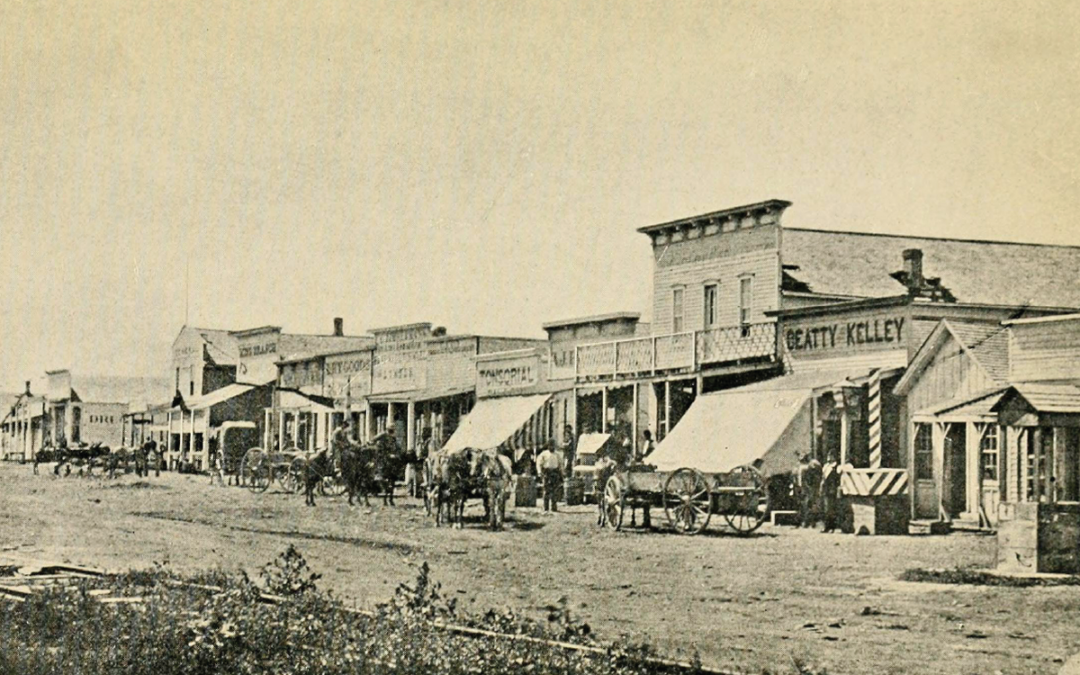

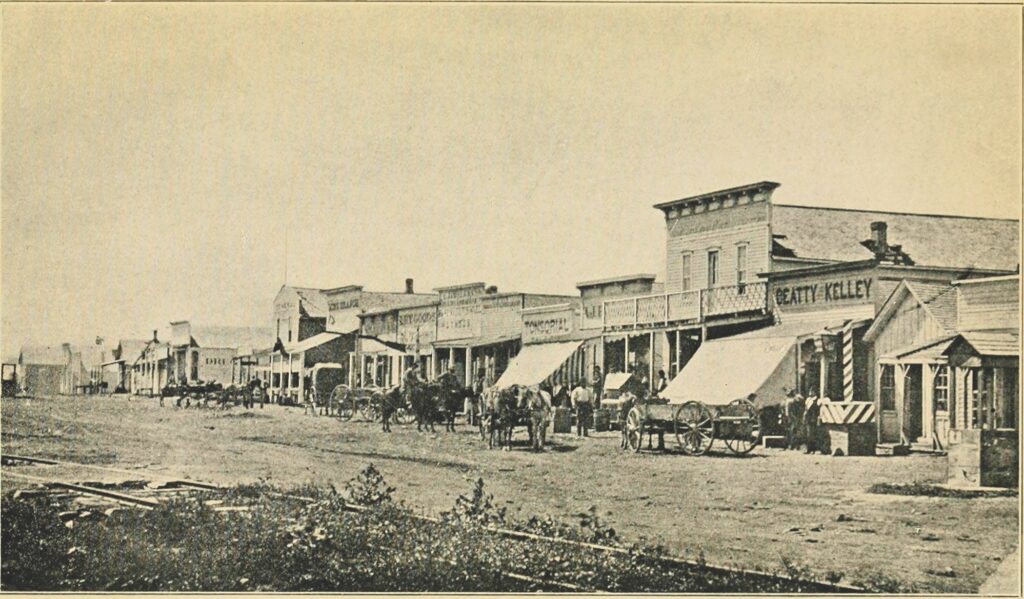

Its most famous sites included near Albany, Texas (Fort Griffin State Historic Site) and Doan’s Crossing on the Red River, not far from Vernon, Texas (Red River Valley Museum), where it crossed into present-day Oklahoma. From there, the trail passed near Frederick (Pioneer Townsite Museum), Clinton (Oklahoma Route 66 Museum, which was formerly the Western Trails Museum), before moving into Kansas to Dodge City (Boot Hill Museum) and beyond—Ogallala, Nebraska (Boot Hill); Miles City, Montana (Range Riders Museum); Deadwood, South Dakota (Adams House Museum); and Fort Burford State Historic Site near Williston, North Dakota.

Some argue that the trail started farther south—in Mexico—and went even farther north (Saskatchewan).

Forgotten sites included places with names like Indian Camp, Red Clark’s Long Horn Roundup on Bear Creek and Mailey’s roadhouse.

What’s in a name?

The trail took on other names—Great Western Trail, Fort Griffin Trail (at least by 1876), Dodge City Trail. Not that names mattered.

“Most everyone has heard of the Chisholm Trail, the Goodnight Trail and the Loving Trail,” George W. Saunders recalled in The Trail Drivers of Texas, “but as a matter of fact most of the trail drivers did not care anything about the name of the trail they were traveling, as they were generally too busy to think or care about its name.”

A son of a Goliad County rancher, Saunders had taken part in his first cattle drive as a 17-year-old in 1871. He was president of the Old Time Trail Drivers’ Association when The Trail Drivers of Texas, compiled and edited by J. Marvin Hunter, was first published in 1924 under Saunders’s direction.

Herding cattle—and lots of horses—wasn’t easy. (It still isn’t.) In another Trail Drivers of Texas account, Saunders recalled a trip up the Western Trail in 1884.

“There were many herds on the trail that year, and we wanted to keep in the lead … so I kept my herd moving forward all the time. I would go on ahead and select herding ground for nights and grazing grounds for nooning, grazed the horses up to these grounds and grazed or drove them off, never allowing them to graze back at all…for I had learned that good time and lots of it was lost by the old way of stopping a herd and allowing it to graze in every direction, sometimes a mile or more on the back trail. In such cases the stock would travel over the same ground twice….”

Competing trail herds weren’t the only concerns on drives.

In 1880, The Caldwell Commercial reported that a cattleman had to stop near the town instead of driving to Ogallala after finding “neither water nor grass on that route” and would have to winter the herd nearby.

End of End of Trails

The Western Trail was longer distance-wise than the Chisholm Trail; it had a longer career (thanks to Kansas quarantine lines) and it shipped more cattle—if we can believe the figures—6 million to 7 million (estimated by some to be as high as 8-9 million) to the Chisholm’s roughly 5 million.

But like the Chisholm and Shawnee, the Western Trail’s days were numbered.

Kansas cattle continued to die from “Texas Fever.” In September 1877, the Inland Tribune of Great Bend, Kansas, reported that a “Col. Stone” had bought 40 cattle in Colorado and driven them across the Dodge City trail, losing 10 shortly afterward to Texas Fever. The newspaper declared: “There is no use talking; the air of the unnaturalized Texas steer is certain death to our civilized cattle.”

In 1885, Kansas declared Texas cattle off limits statewide, and proposals for a “national” cattle trail from Texas to the northern ranches and markets never materialized. As The (Denison, Texas) Sunday Gazetteer remarked that May:

“When the Fort Worth refrigerator works go to shipping beef again the Western cattle trail will be replaced by the Missouri Pacific.”

Those trail-driving days were soon over. Cattle drives would be done by railroads.

Which J.G. Reed had predicted years earlier.

“There will always be a big supply in the State [of Texas],” he said back in 1881, “but from year to year there will be fewer cattle driven north, until that business will be abandoned altogether, Texas will become the cattle market, and even now we are getting our price there.”

A Wide Spot in the Road

Fort Robinson State Park

All surviving Old West military forts, whether reconstructed, ruins or still active, have rich histories—but few can match Fort Robinson in the heartache department.

The destination of John T. Lytle’s cattle drive that opened the Western Trail when he drove a herd to the Red Cloud Agency in 1874, Fort Robinson is site of Crazy Horse’s death in 1877 and the Cheyenne Breakout of 1879 that left 64 Indians and 11 soldiers dead.

Established in 1874, the post remained active until 1948. It became a Nebraska state park in 1956 and a National Historic Landmark four years later.

Today the park is home to historic buildings, cabins, 22,000-plus scenic acres to explore and bison and longhorn herds. Lodging is available in former officer’s quarters, dating from 1874 to 1909, and the 1909 enlisted men’s quarters. Tent and camper sites are also available. outdoornebraska.gov

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: Cattle Drive & Bull Bar, Coleman, TX; Vernon Burger, Vernon, TX; Wagg’s BBQ, Woodward, OK;

Open Range Grill, Ogallala, NE

Good Lodging: Dixie Dude Ranch, Bandera, TX; Sayles Ranch Guesthouses, Abilene, TX;

Hampton Inn & Suites, Dodge City, KS; Historic Olive Hotel, Miles City, MT