The American cowboy is not only a universal symbol of the American West, but he is also a symbol of the American spirit.

The American cowboy is not only a universal symbol of the American West, but he is also a symbol of the American spirit.

His gear—hat, chaps, boots, spurs, saddle—are as much apart of his makeup as is his can-do attitude, a temperament that is embodied in the words for sucking up your pain and doing what has to be done: “Cowboy up!”

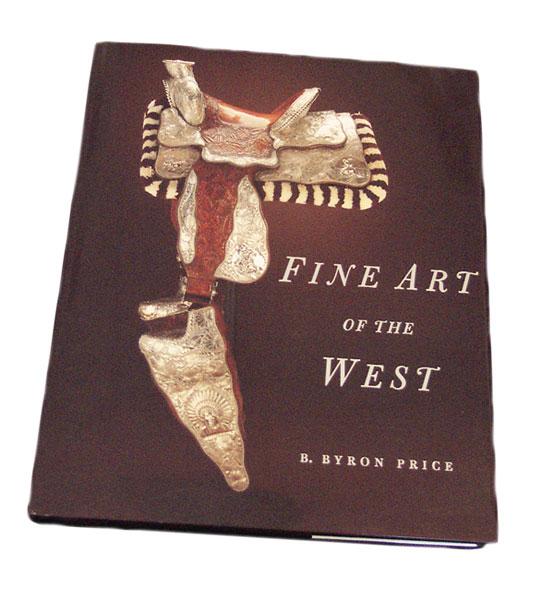

B. Byron Price, in his book Fine Art of the West, recounts the history of cowboy equipment, from its Spanish roots to today. Em-bellished with historical images and photographs of the finest modern collections of Western gear, the book is a visual feast.

True West is proud to present a selection from Price’s book on the history of the Western saddle.

The rising economic importance of the western range cattle industry and the steady flow of farmers into the post-Civil War West stimulated an unprecedented demand for quality saddlery and harness. The develop-ment of a railroad network and tanning facilities and the availability of a greater number of skilled craftsmen, many of them Mexican and European immigrants or eastern transplants, also hastened the growth of the saddle-making industry in the trans-Mississippi West. Lower labor, leather, and saddletree costs played crucial roles and enabled western saddle makers in such centers as St. Louis, Omaha, Denver, Cheyenne, and San Francisco to wrest the saddlery market away from their East Coast competitors by 1875.

Craftsmen in these and other com-munities began to supply cowboys with heavy-duty stock saddles weighing as much as forty pounds and designed to withstand the rigors of life on the open range. In the 1870s saddle architecture evolved rapidly from the simple mochila housings and single-cinch styles of the past into heavier and more elaborate double-rigged creations bearing two cinchas and separate skirts, jockeys, and fenders. Trendsetters also tinkered with the size, shape, and configuration of saddletrees, and by the latter part of the decade, inventors in Texas and Colorado had strengthened some types with metal horns and forks. During the 1880s distinctive regional styles, based primarily on structure and rigging rather than ornamentation, developed in California and Texas and on the Great Plains.

Because they were made of thick skirting and subject to hard use, stock rigs did not lend themselves to the decorative leather fringe, cloth braid and embroidery, and decorative stitching prevalent on the soft leather saddles of the late nineteenth century. And while a few cowboys rode “kaks” made of black leather, there was never much demand among range riders for saddles with dyed skirting, which tended to fade when exposed to the sun and prolonged wear.

Cowboys with an artistic bent sometimes added their own dec-orative touches to their rigs, forming simple designs with brass nails and tacks or trimming skirts and cantles with rattlesnake skin or bearskin. Most, however, preferred the look and feel of saddle leather that had been hand-carved and stamped. Besides lending a decorative effect, stamping, also known as “sharking” or “tooling,” tended to compress the fibers of saddle skirting, thereby adding to its durability. Some makers believed that stamped and carved saddles wore as much as 50 percent longer than plain ones. One old-timer claimed to have stamped leather so deeply that it “could be used for a door mat without wearing out.” Stamp work also shed water more easily than slick skirting.

Malleable when dampened, tanned cowhide with a soft, fine grain lent itself to carving, stamping, and embossing in high relief. The quality of such embellishment, however, depended on the type and prep-aration of the leather as well as upon the skill of the artisan. In the last quarter of the nineteenth century, California tanneries began to pro-duce commercial quantities of a superior oak-tanned skirting favored by stock saddle makers throughout the West. Possessing a white, velvety grain, California leather wore better than other varieties and was especially conducive to stamping and carving. Successful saddle stamping, wrote one observer in Harness magazine in 1889,

depends upon having leather in the condition to hold the creases made by the tool, and not to draw out lines already made. There is something in the skirting leather tanned on the Pacific coast which specially fits it for embossing….the grain is so flexible that when once creased, the line cannot be removed.

Before the embellishment process commenced, however, makers cut out the various parts of the saddle from a side of leather, avoiding material that was marred by brands or “flanky,” meaning thin, weak, or wrinkled. After scouring the flesh side of the pieces with a stiff brush, pumice, and water, the craftsman left them to dry in the shade or covered them with burlap, so they would not darken in the sun.

Properly “sammied” (moistened) leather was soft and pliant and, if well tanned, retained moisture uniformly over the entire surface. Because no two pieces of skirting responded in the same way to scouring, experience was paramount in determining the correct conditions for embossing and carving. The stamper began to shark the grain side of the leather when it was nearly dry, moistening the surface lightly with a soft sponge when it became too parched to hold the impression of the stamping tools. Care was taken, however, not to discolor the leather by applying too much water.

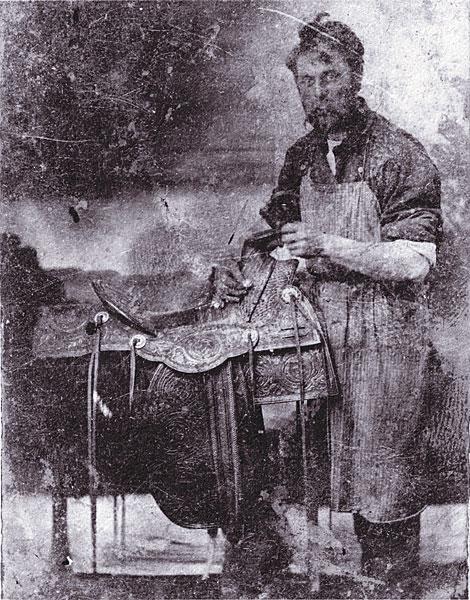

Leatherworkers pursued their craft with a sturdy set of specialized hand tools, many of ancient origin and some adapted from implements used in the wood- and metalworking trades. British companies dominated the American market for leatherworking equipment until the Civil War when a group of Newark, New Jersey, foundries, led by C. S. Osborne & Co., became serious competitors in the field. Tool makers created a wide array of products including blades, gauges, and creasers of various shapes and sizes used to cut, split, skive, and carve leather; awls and punches to make holes for thread and tie strings; hammers to drive nails and tacks; and rawhide-covered mallets, mauls, and “stamping sticks” to tap ornamental embossing dies.

In 1890 only about 10 percent of American saddle shops reported using any sort of machinery in the production process. To lower labor costs and turn out mass-market merchandise more quickly and uniformly, however, many large-scale saddleries, including some in the West, turned increasingly to assembly-line methods and machinery. Despite the fact that pinking machines, screw presses, and mechanical creasing and embossing wheels could produce an almost limitless assortment of decorative motifs with speed and precision, their output inevitably lacked the texture, character, and eccentricity of handwork. To remedy these shortcomings, saddle makers who employed such equipment, and even some who did not, often retained the services of talented specialists, known as “stamp hands,” to embellish their finest products on a piecework basis.

Despite individual examples of creativity and innovation, much of the western saddlery produced in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries was run-of-the-mill and abounding with repetitive designs and discordant patterns. Critics blamed such ills on the saddle and harness industry for failing to reward creativity or encourage the development of artistic skills such as freehand drawing. Articles appearing in leatherworking trade publications often bemoaned the dearth of theoretical and practical knowledge of design among the industry’s journeymen and the stagnation and distortion of nature it produced. “A business that is represented by fifteen thousand employers and a hundred thousand operatives,” wrote one detractor in 1881, “ought not to be in such a condition, and it is time the leaders get out of the rut, and by starting in a new direction give an impetus to the trade that will lift it from its present inertness.”

Advocates for change urged leather craftsmen to strive for greater variety in designs and to produce more restrained, tasteful, and congruent compositions with a closer fidelity to nature. “Nature is prolific,” declared one authority, “and the artist needs only to copy from what he sees around him, selecting his forms from such leaves or flowers as best harmonize with the form of surface to be covered.” Some experts believed that training in design and draftsmanship would help apprentice saddle makers to distinguish between crudity and refinement and thus create more pleasing motifs in their work.

During the debate over the state of craftsmanship and design in western-style saddlery, commentators both praised and belittled the work of Hispanic saddle makers. In 1878, for example, one writer called Mexican craftsmen “wonderfully skillful in designing and ornamenting saddles…

doing their work more rapidly and in a better manner than the most expert American.” A few years later, however, another author excoriated Mexican saddles as inferior and a “degenerated imitation” of their finely stamped Moorish-Spanish ancestors. “Em-bossing leather is one of the old arts,” he ranted, “and one in which the present generation is far behind generations of the past.” The writer of another article during the same period called Hispanic artisans “skillful” in making stock saddles, “but without taste as designers.” Mexican “indolence,” he averred with more than a little prejudice, “showed itself in the want of character” of their designs. In-comprehensibly, this same anonymous pundit praised the high-quality workmanship and ornamentation of Texas- and California-made saddles, many of which were also the products of Hispanic craftsmen.

Western stock saddle design and craftsmanship reached its zenith in California, beginning with the work of a host of talented immigrants from Mexico and Central and South America who arrived in the wake of the Gold Rush of 1849. The newcomers brought with them tools, methods, and decorative styles that differed from those of most American leatherworkers. In contrast to eastern-trained saddle makers, Hispanic carvers usually rendered the outlines of their ornamental patterns freehand instead of committing them to paper and then transferring them to the leather with an ivory point or hard lead pencil. Hispanic talabateros also relied on fewer tools, many times homemade from “old files or bits of steel with ends ground to the required shape.”

B. Byron Price is the director of the Charles M. Russell Center for the Study of Art of the American West at the University of Oklahoma. His book, Fine Art of the West, is available from Abbeville Press (800-ARTBOOK; www.abbeville.com) and where fine books are sold. All photos courtesy Abbeville Press retain the caption information used in the book.

High in the Saddle Again

Casey Jordan’s 16” half-seat saddle with tooling patterned in a Main and Winchester style and Sam Staggs’ rigging. This is Jordan’s third full-size saddle made under his own stamp, although he has made about 50 for Blue Ribbon Custom Saddles in Phoenix, Arizona.

Casey Jordan’s 16” half-seat saddle with tooling patterned in a Main and Winchester style and Sam Staggs’ rigging. This is Jordan’s third full-size saddle made under his own stamp, although he has made about 50 for Blue Ribbon Custom Saddles in Phoenix, Arizona.

– Courtesy Casey Jordan –

The time-honored tradition of saddle making was recently reflected in an exhibition titled “Art of the Saddlemaker—A Gathering of Handmade Saddles and Fine Leather,” held last fall in Colorado Springs at the ProRodeo Hall of Fame. Twelve saddle makers from eight states and Canada submitted juried entries, providing a brilliant look at the current state of the saddle maker’s art. Finely tooled leather and richly tanned hides covering handmade trees, cantles and pommels made each entry a unique sum of many well-made parts. Created for use and for show, the collection was dazzling in design integrity and beauty, each saddle a personalized extension of its maker.

Reflecting regional and stylistic differences, as well as signature trademarks, the collection included not only saddles, but also leather accessories like chinks, cuffs, purses and saddlebags, and “salesman samples,” small scale replicas made by Casey Jordan of Phoenix, Arizona, proving that the creation of cowboy gear is a vehicle for personal expression as much as any other art form. Other contributors included Alan Dewey, Yakima, Washington; Ross Ellas, Alberta, Canada; Jim Kelly, Price, Utah; Bob Klenda, Fort Morgan, Colorado; Kay Orton, Collbran, Colorado; Keith Seidel, Cody, Wyoming; Jesse Smith, Pritchett, Colorado; Larry Smith, Pendleton, Oregon; Sharri Smith, Pritchett, Colorado; Chuck Treon, Weatherford, Texas; and Ricardo Vigil, Albuquerque, New Mexico.

The show was presented by the Colorado Saddle Makers Association, an organization which now has members from throughout the U.S. and Canada. Judging criteria included the use of natural materials, composition, tooling, engraving and stamping. Styles represented included Vaquero or Spanish (California), Buckaroo (Nevada) and others designed mainly for roping or pleasure. Reflecting the saddle’s intended use, some had wide pommels—practical for mountainous areas—while others had narrow ones—preferable for sport or ranch work. High cantles contrasted with lower profile saddles, especially those with the elegant and comfortable turn-back, or Cheyenne roll. Whether looking at showpieces or working saddles, viewers could appreciate the emphasis on flow and line created by parallel skirts, split fork seats, just the right scale pommel and horn, and other details.

Diverse elements in the 12 entries, reflecting centuries of traditional techniques, included lavish carving (especially complex florals and rosettes), basket stamping, eye-catching contrast latigo leathers for lacing, quilted seats and beautifully etched silver conchos, stirrup irons and nameplates. As an example of a fully carved saddle, Jim Kelly’s entry told an illustrated story in fine relief carving on both the front and back skirt panels.

This memorable show and its members proved that the art of the saddle maker, so essential to the horse culture and, at its best, still done entirely by hand, is alive and well in the modern West.

—Corinne Brown

{jathumbnail off images=”images/stories/JanFeb-2005/jf05_saddle_up_casey_jordan_16_half_seat_saddle.jpg”}

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Mort Fleischer Collection –

– Courtesy Mort Fleischer Collection –

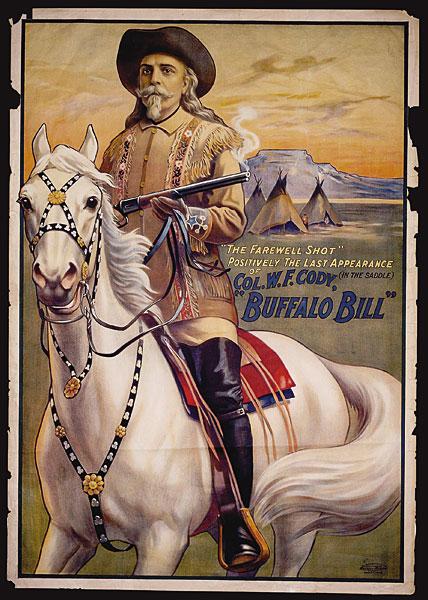

– U.S. Lithograph Co., Russell-Morgan Print, 40.5 x 28 in. Courtesy Abbeville Press / Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming –

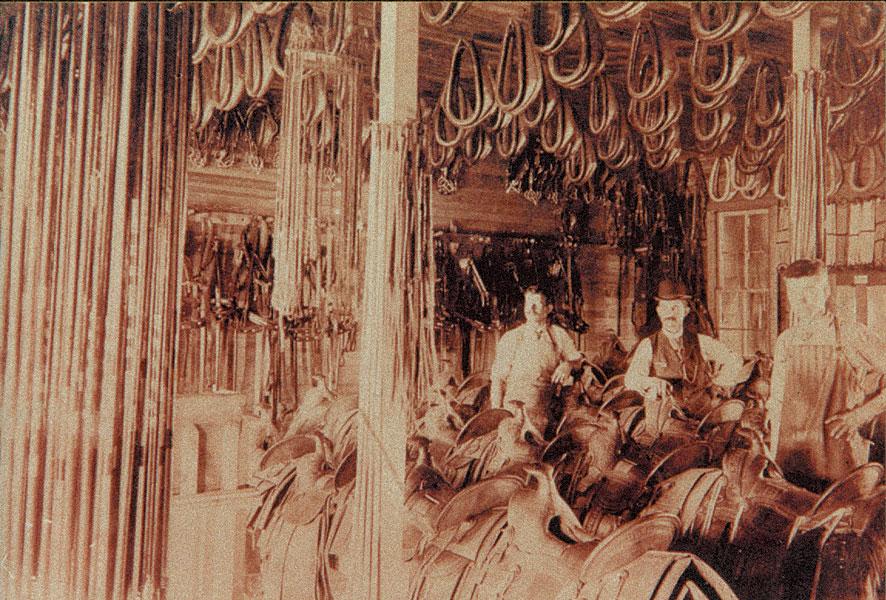

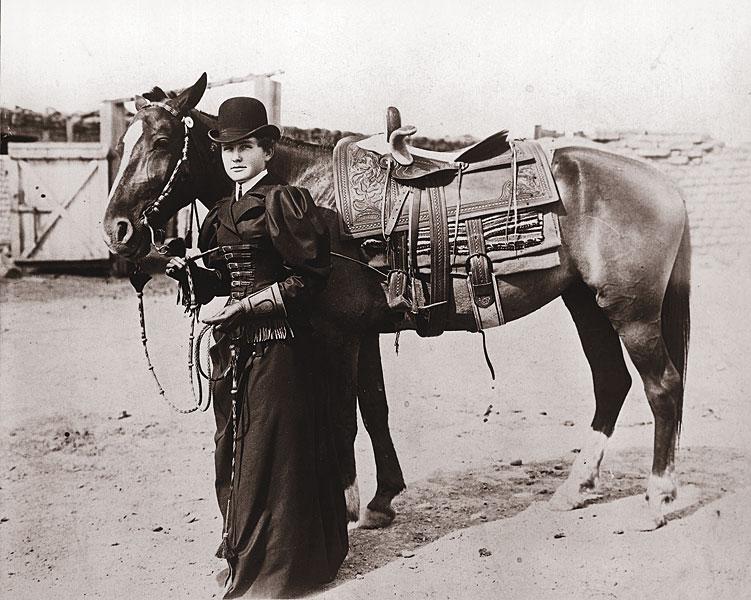

– Courtesy Abbeville Press / Panhandle Plains Historical Museum Collection, Canyon, Texas –

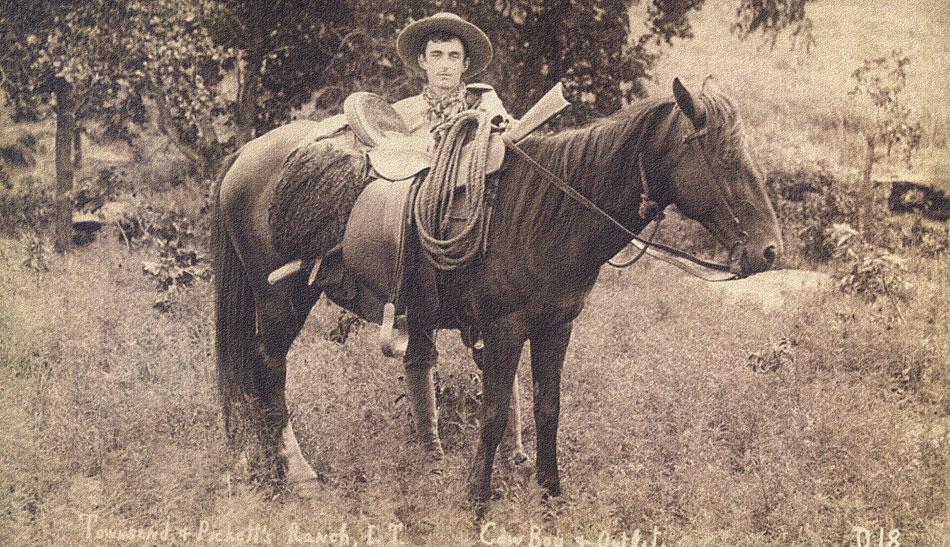

A good example of an 1890’s saddle found at Townsend & Pickett’s Ranch, Indian Territory.

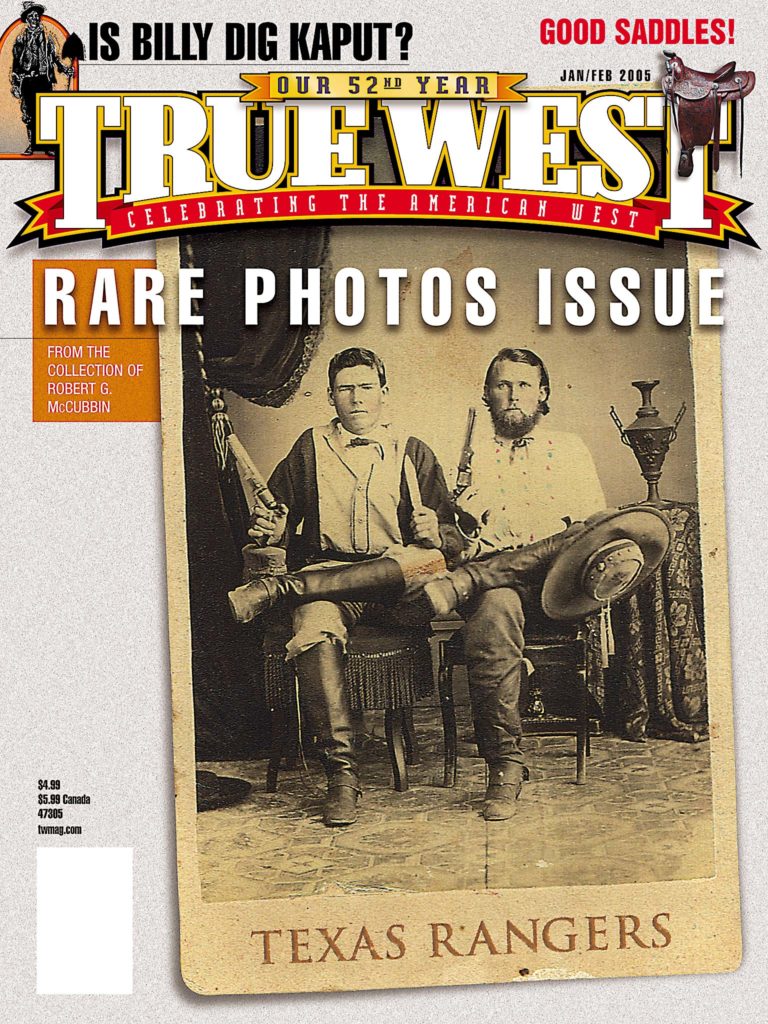

– Courtesy Robert G. McCubbin –

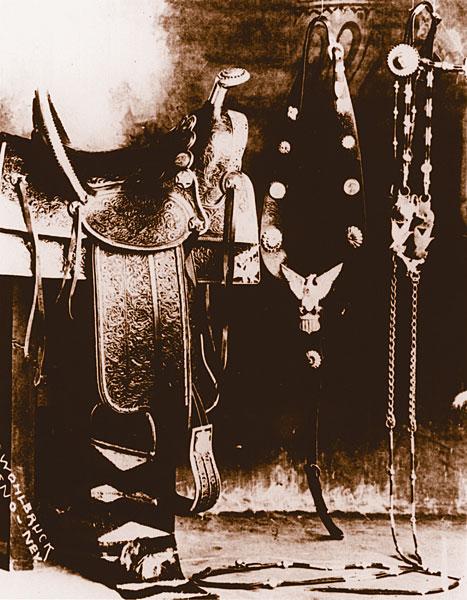

– Courtesy Abbeville Press / Northeastern Nevada Museum, Elko –

– Courtesy Abbeville Press /Panhandle Plains Historical Museum Collection, Canyon, Texas –

– Courtesy Mort Fleischer Collection –

– Courtesy Mort Fleischer Collection –

– Courtesy Abbeville Press / Northeastern Nevada Museum, Elko –

– Courtesy Mort Fleischer Collection –

– Courtesy Mort Fleischer Collection –

– Courtesy Abbeville Press / Kansas State Historical Society, Topeka –