Author Mark Twain likened the stagecoach to “an imposing cradle on wheels,” referring to the consistent sway of the vehicle that made some passengers seasick.

Author Mark Twain likened the stagecoach to “an imposing cradle on wheels,” referring to the consistent sway of the vehicle that made some passengers seasick.

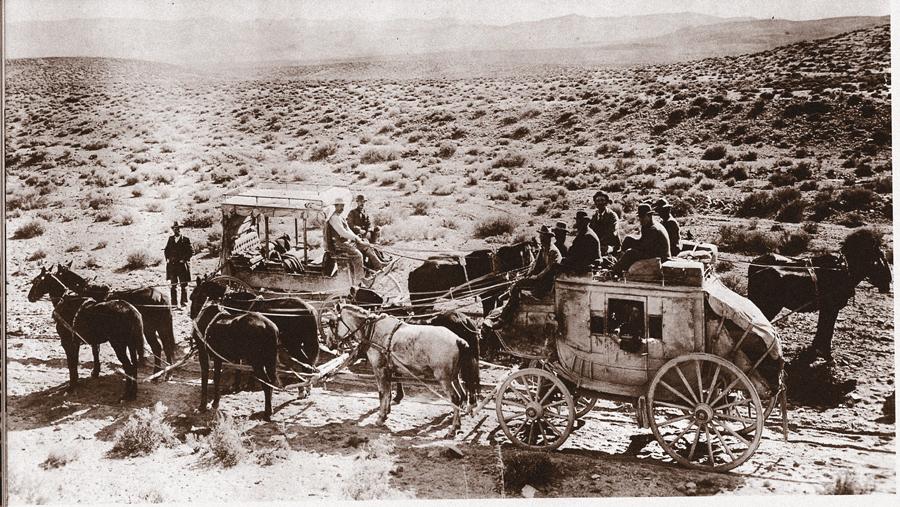

Twain recorded his 1861 ride aboard Ben Holladay and Wells Fargo stages from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Carson City, Nevada, in his 1872 book, Roughing It. Passengers were limited to 25 lbs. of baggage, but sometimes even that luxury was too much for a stagecoach to handle. When traveling near Carson Sink, the humorist recalled crossing “forty memorable miles of bottomless sand, into which the coach wheels sunk from six inches to a foot. We worked our passage most of the way across. That is to say, we got out and walked.”

Stage stations’ unsavory grub

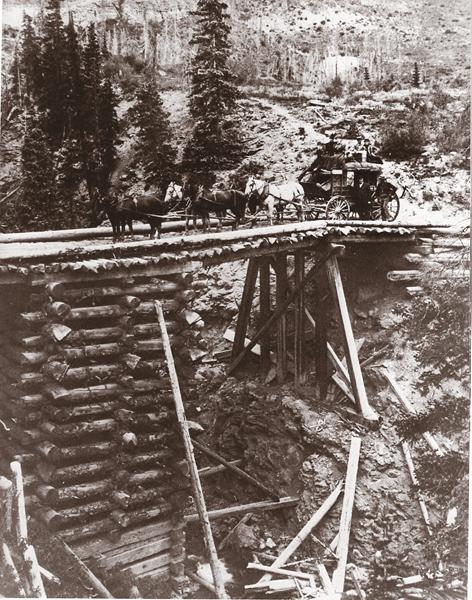

During the heyday of coaching from 1850-69, stages carried passengers, mail and valuables. Passengers often risked their lives to journey westward; in addition to cramped quarters on the coaches and unsavory grub at stage stations, they occasionally had to endure robberies, Indian attacks and accidents.

Twain’s observations about breakfast at a stage station in 1861 give no doubt about the poor provisions. The meal consisted of “last week’s bread … condemned army bacon … a beverage which … pretended to be tea, but there was too much dish-rag, and sand, and old bacon-rind in it to deceive the intelligent traveler.”

Twain may have exaggerated in his stories, but not by much when it came to the food. Journalist Bayard Taylor also rode one of Ben Holladay’s stages, traveling from Fort Riley, Kansas, to Denver, Colorado, in June 1866. In Cheyenne Wells, Colorado, the stage stop consisted of “a large and handsome frame stable for the mules, but no dwelling.” Taylor said the people lived “in a natural cave,” but travelers enjoyed better food: “antelope steak, tomatoes, bread, pickles, and potatoes—a royal meal, after two days of detestable fare.”

New York Herald reporter Waterman L. Ormsby was the first through passenger on the Butterfield Overland Mail Company line from St. Louis, Missouri, to San Francisco, California, via El Paso, Texas. In September 1858, he wrote of the grub he had purchased at a typical stop at Capt. John Pope’s camp in Texas’ Llano Estacado. (Meals were paid separately from the $200 tickets.) His routine evening meal consisted of shortcake, coffee, dried beef and raw onions.

Both the Butterfield and Ben Holladay stages crossed the terrain at roughly the same speed. Ormsby’s trip covered 2,812 miles of the Butterfield line’s “Oxbow Route,” including 162 miles by rail, in just over 24 days (117 miles per day). On Taylor’s trip, the Ben Holladay stage traveled 476 miles in four days and six hours, averaging 112 miles per day.

Queasy cradles on wheels

Some Concord coaches, the most popular of the day, could carry up to 12 people on top and nine inside, and offered three comfortably padded leather seats. Most stages seated six, nine or 12 passengers. Valuables were kept in the front boot, stored beneath the driver’s seat, while other baggage was placed in a leather boot in the back. Thoroughbraces, which were leather straps stretched front to back underneath the coach, aided management of the mule or horse teams pulling the stages, but the braces caused a rocking motion that made some travelers queasy.

J.M. Farwell, a journalist for the San Francisco Alta California, left that city on October 16 and arrived in St. Louis, Missouri, on November 9. He reported:?“My notes along the road have been written under very embarrassing circumstances, six persons having been crowded into a coach intended for one-half the number, and the jolting and jamming being decidedly troublesome.”

A Wells Fargo takeover

Wells Fargo later assumed control of the Butterfield Overland Mail and then bought out Ben Holladay’s stagecoach interests, before wisely switching to the railroad business after the 1869 completion of the transcontinental railroad.

But for at least 40 more years, stagecoaches still operated, especially in isolated regions where railroads could not reach. Even in areas where trains did go, coaches were ridden by pioneers who could afford a dream, but not a rail ticket.

Lori Van Pelt is the author of Capital Characters of Old Cheyenne, the second book in her Dreamers and Schemers series.

Photo Gallery

– All photos True West Archives –