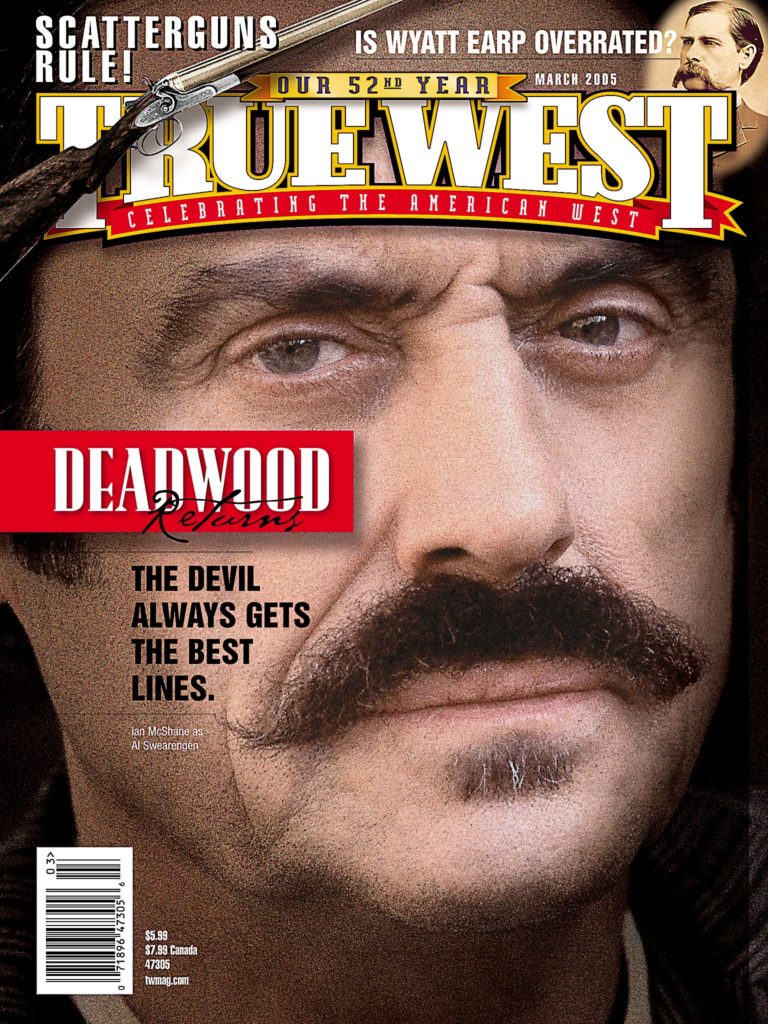

More than any six-gun or rifle, the shotgun could easily be called the “gun that won the West!”

More than any six-gun or rifle, the shotgun could easily be called the “gun that won the West!”

Despite the acclaim given to the six-guns and rifles of the Old West, when it came to getting the job done, whether it was used to control a boisterous, hell-bent crowd, protect (or take) a gold shipment or for hunting, the smoothbore shotgun was the Westerner’s hands-down favorite.

With the discovery of gold in California, thousands of eager fortune seekers surged out of the eastern half of the United States, as well as from foreign lands. These hardy Argonauts brought with them every description of personal armament imaginable, including a goodly assortment of shotguns.

Of course, shotguns and other smoothbore weapons, such as single barrel fusils, often known as “fusees,” had been in use by red man and white from the earliest times in the West. By 1849, the double-barrel shotgun was probably the most popular civilian smoothbore in the West. Most gun shops kept at least a small stock of these scatterguns on hand, including both domestically produced and imported arms from countries such as England, Germany and France. Imported guns—especially those from Great Britain—were in such demand that some of the foreign manufacturers placed their own ads in American newspapers.

Self-contained Cartridges

Although this was the age of the muzzleloader, the shotgun quickly took advantage of self-contained—or at least partially self-contained cartridges.

Thanks to a handy invention known as the “Eley wire cartridge,” shotgunners could greatly reduce the time involved in charging a muzzle-loading shotgun. This product, sold by the Eley Brothers—famed British ammunition producers—was constructed using a cylindrical, soft copper, mesh sleeve, which contained a load of pellets. Packed in bone dust to resist deforming, these pellets varied in size from birdshot to buckshot. This wire mesh cartridge had an outer wrapping of paper to keep every-thing in place. To use it, one simply poured the powder charge into the gun’s bore, dropped a wire cartridge into the muzzle over the charge, and with the ramrod, rammed the entire load in place. This not only made loading faster and easier, but because the wire mesh stayed with the pellets for some distance once the shot charge left the gun’s bore, the shotgun’s effective range was lengthened con-siderably.

Breech-loading Shotgun

Even with the aid of these early self-contained cart-ridges, such as they were, by the early 1850s, it became evident that the muzzle-loader’s days were numbered. At the London Exhibition of 1851, the French arms-making firm of Casimir LeFaucheux displayed its new breech-loading shotguns. These simple, yet effective pinfire guns, which utilized the same basic design as would be seen in most of the successful double-barrel breech-loading shotguns of the near future, owed most of their success to a metallic cased cartridge. By the end of the decade, Westerners had a variety of breech-loading shotguns available to them, including Colt’s Model 1855 revolving shotgun and the Sharps single shot.

Ironically though, neither of these American scatterguns ever gained much popularity, primarily because they did not use a metallic cartridge to prevent gas leakage around the chambers and breech. The old front loader died a hard death.

Simplicity in Design

Ever since the invention of firearms, most successful firearms have been muzzle-loaded. In remote areas such as the Western frontier, resupply of ammunition could be a critical factor. It was much easier to obtain the more traditional loose powder, lead and percussion caps than it was to purchase “newfangled” metallic cartridges. Muzzle-loading shotguns—especially double-barrel models—could also use almost any load in such arms. Even military officers of the day relied on civilian double-barrel scatterguns during their Western tours of duty.

An officer in the Regiment of Mounted Rifles recalled a hunting foray that took place around 1850, when he ventured alone into a canyon in Indian country in search of birds for the camp table. He loaded one barrel of his double with No. Six shot, while the “other held nine buckshot for Indians.” Later, in 1856 Texas, a rancher surprised a raiding party of Indians who had been marauding his ranch on a regular basis. With his double-barrel scattergun loaded with a charge of nine revolver balls and 30 buckshot in each barrel—a stout load indeed—he killed two and seriously wounded a third during one of their unfortunate forays. At this time too, rifled slugs for shotguns were being introduced, adding to the muzzleloader’s versatility.

Military Surplus Gun

In the tumultuous post-Civil War West, a shotgun was a handy piece of hardware. In the lawless territories of the 1860s, a traveler was considered “undressed” unless he had at least one gun with him. Often, a shotgun was the arm of choice—especially to those involved in an outdoor occupation, such as a rancher, stagecoach guard, hunter, lawman and so on.

With greater numbers of people moving westward, the demand for inexpensive, reliable arms brought about a new addition to the firearms market—the military surplus gun. With thousands of unneeded rifle and muskets in government stores, many of them were sold to civilians. A good number of them were altered to single barrel shotguns by shortening the fore stock and adding a bead-type front sight. If the gun had been rifled, the bore could be reamed out or “draw bored” to smoothbore for handling shot loads.

In good supply, guns of this ilk cost only a couple of dollars, while the newer breechloaders fetched several times that amount. The 10-bore gun was highly prized and was often considered the most useful for all-around work. The 12 gauge too was a popular choice because of its power and the hefty charges that could be stoked into it. Sixteens, 20s and other smaller bored guns were plentiful, but as with today’s shooters, were only considered good for specialized shooting.

Most shotguns as they left the factory were deemed too big and cumbersome for the confined spaces of certain uses, and according to one Colorado settler of the period, “a shotgun’s not very handy at close quarters, unless it’s a sawed-off. For fighting in a bar room, let me tell you, or on top of a stage coach, they like to cut the barrel off a foot in front of the hammers, so the gun handles more like a pistol.”

Shotgun makes its mark

Throughout the 1870s, minor improve-ments were made in breech-loading shotguns, making them stronger and less prone to wear. Ironically, with the advances in firearms technology moving so rapidly, the single barrel shotgun enjoyed a popularity revival, if for no other reason than the economics of construction and sales of such arms. It was during this time, too, that American shotguns were gaining favor and acceptance on the frontier.

Some U.S. firms that were rifle producers entered the shotgun market with inexpensive smoothbore versions of their single-shot hunting rifles. Companies like Remington and Stevens produced shotgun barrels for their rifle actions, while the Maynard firm sold its guns with interchangeable 20- and 28-gauge shot barrels in varying lengths.

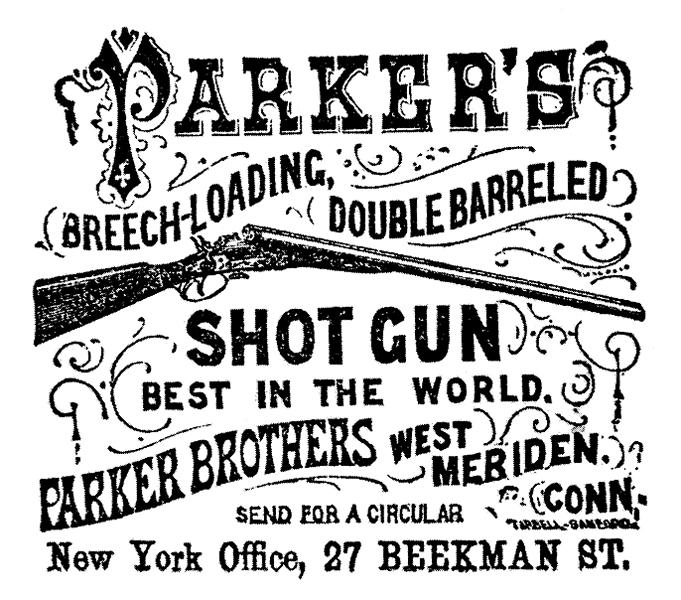

Nevertheless, given the state of ammunition and the simplicity of the older designs, single and double-barrel shotguns reigned supreme, with the double scattergun being number one in sales. Side-by-sides, like the Parker, Remington, the American Arms Company’s Fox model and the Colt, were among America’s offering of the times. Smoothbores of this ilk generally sold for around $50 for the plain models and $75 for those sporting better finishes. Of course, there were other gun makers, domestic and foreign. While Yankee shotgun manufacturers were indeed taking a bite out of the import market, the fine British doubles remained the first choice with those who could afford them. Yet, regardless of where it was made, the double was still the shotgun of the 1870s.

Hammerless shotguns

While the more traditional exposed hammer double-barrels continued to dominate the shotgun scene throughout the rest of the Wild West period, hammerless guns, introduced in the late ’70s, began to gain favor with Western shooters by the early to mid-1880s.

Although some hammerless shotguns did not survive the Old West itself, many well-known makers continued to produce quality shotguns well into the 20th century. Names like L.C. Smith, Parker, Remington and Stevens all got their start making black-powder double-barrel shotguns, many of which sold in the Western market.

Converted Military shotguns

In a seemingly backward step, but in reality simply a trend governed by econ-omics, the single barrel shotgun continued to main-tain its attractiveness rather than lose it. New guns sold as well as ever, even as gun sellers converted military metallic cartridge rifle actions into saleable shotguns.

Surplus Springfield trap-door actions were mated to smoothbore 16- or 20-gauge barrels and attached to “plain Jane” stocks, selling for around $12 each. These were really just civilian versions of the government M-1881 shotgun, in use with various army units throughout the frontier.

Another single-shot scattergun based on a military arm was the “Zulu,” which was made from scrap Snider-type actions. By using this British-designed, hinged breech-action, 12-gauge guns could be assembled and sold for as little as $4 apiece.

Despite the abundance of these and other inexpensive smoothbores, in general, quality guns still ruled the roost for serious shooters.

Repeating shotguns

By the mid-’80s, technological advances allowed newly designed repeating shotguns to be taken seriously.

In April 1882, Christopher Spencer, inventor of the famed seven-shot repeating rifle of the Civil War, patented his pump-action design for rifles and shotguns. Although few rifles were ever produced, Spencer’s shotgun, a six-shot arm produced mostly in 12 gauge, achieved a modicum of success and was made by the Spencer Arms Co. until around 1889, when the firm fell into difficult times. The giant war surplus dealer of the day, Francis Bannerman and Sons, bought Spencer’s patents and continued to manufacture these repeaters until around 1907.

The Spencer is generally credited with being the first widely accepted repeating shotgun, and it led the way for other multi-shot smoothbores, which helped bring an end to the double-barrel’s reign as king.

Five years later, Winchester began marketing its John Browning-designed Model 1887 lever-action shotgun, a six-shot scattergun that found favor with professional Old West shootists such as Arizona Sheriff John Slaughter and Texas gunman George Scarborough. It was also the choice of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad, which considered it the best shotgun for arming its messengers.

Slide and Pump Actions

Initially, the 1887 model was the most popular repeating smoothbore of its time; however, within a few years it was eclipsed by Winchester’s Model 1893 slide-action shotgun. Nonetheless, during its 14-year production run, nearly 65,000 Model ’87s left the factory.

The ’93 model’s inability to handle the then-new smokeless powder ammunition caused its demise, but it was soon followed by an improved pump-action shotgun, the famed Model 1897. With well over a million of these guns produced between 1897 and 1957, this gun was one of the best selling shotguns in Winchester’s history, and it was an immediate success with Western shooters.

A Tamer West

As America moved into the 20th century, the Old West passed into history. Progress, in the form of the plow, pavement and the automobile, crossed the West’s old cattle trails and wagon ruts of previous decades. The buffalo were practically all gone, save for a few protected herds. The Indians, too, once proud and defiant, were eking out a meager existence in isolated reservations, and gunfighters were shooting it out in silent films … ironically, in studio sets located in the East!

The new West was a tamer breed, yet some of the tools of its colorful and raucous past were still needed. The shotgun was one necessity that lived on. Improved and refined, these smoothbore arms continued to serve Westerners in the modern world, as they had when the frontier was young and wild. The scattergun was still a reliable hunting companion, a trusted friend or a formidable foe.

Whatever the reason for its use, there’s no denying that the shotgun was one of the most widely used firearms in the Old West, and more than any six-gun or rifle, the scattergun could easily be called the “gun that won the West!”

For further reading, the author recommends Firearms of the American West 1803—1894, Volumes I and II, by Louis A. Garavaglia and Charles G. Worman, published by University of New Mexico Press.

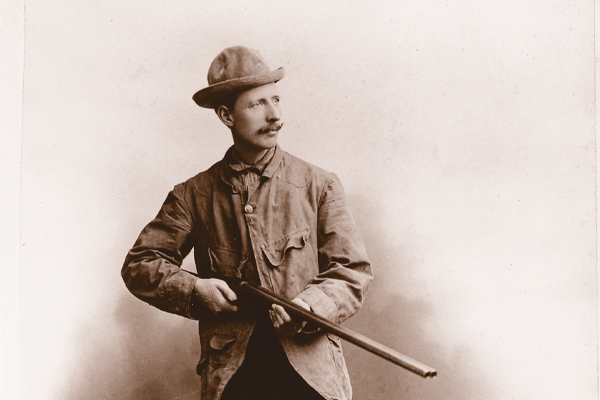

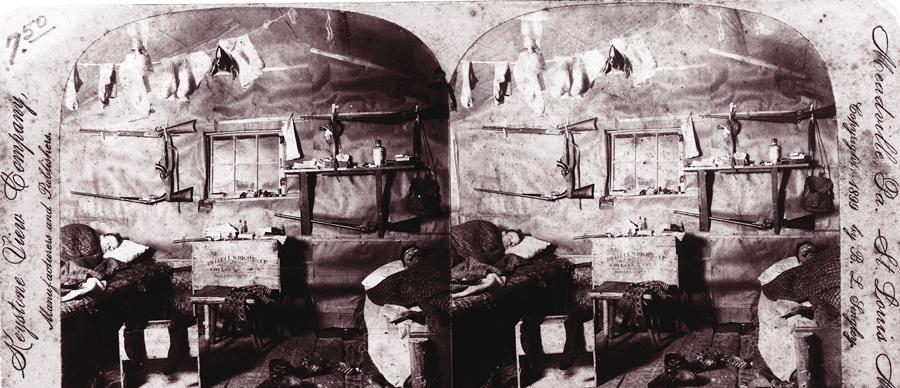

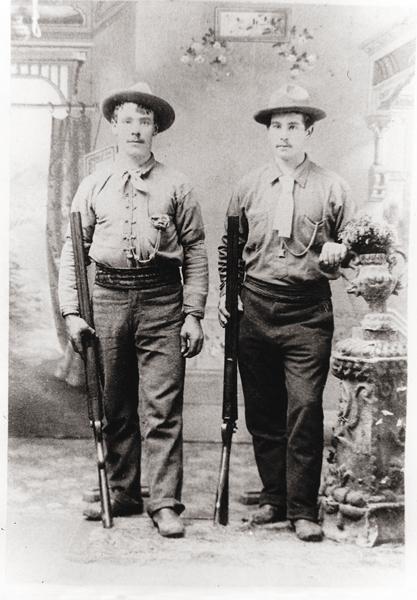

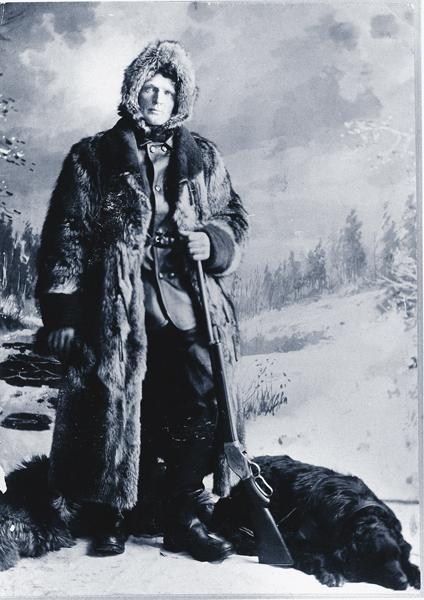

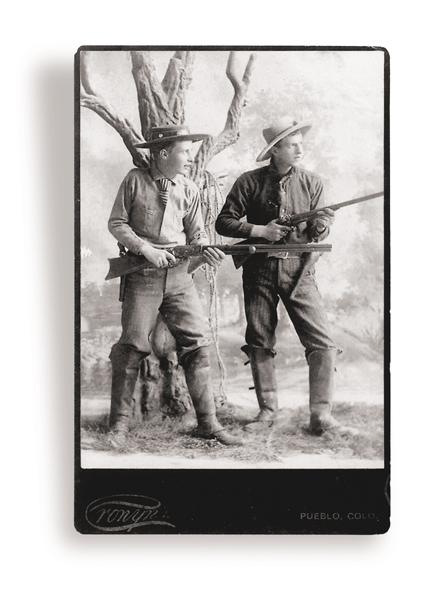

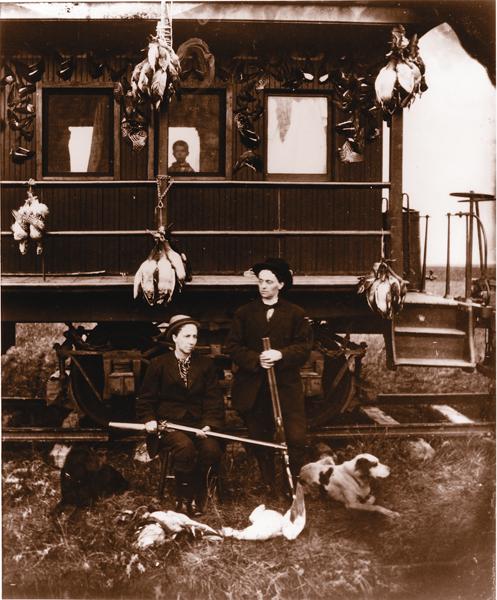

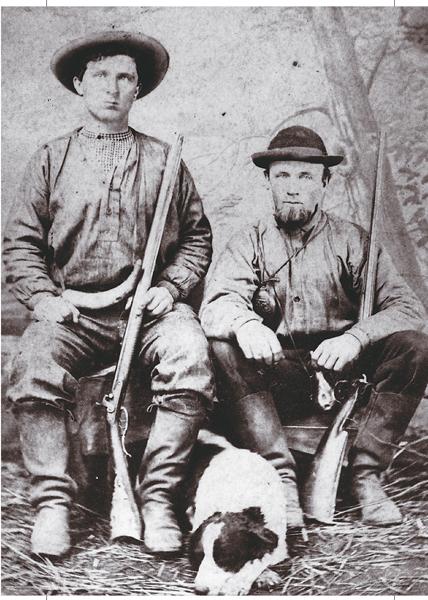

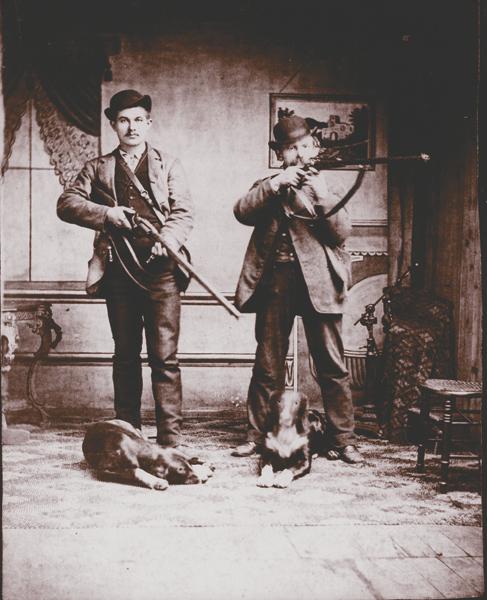

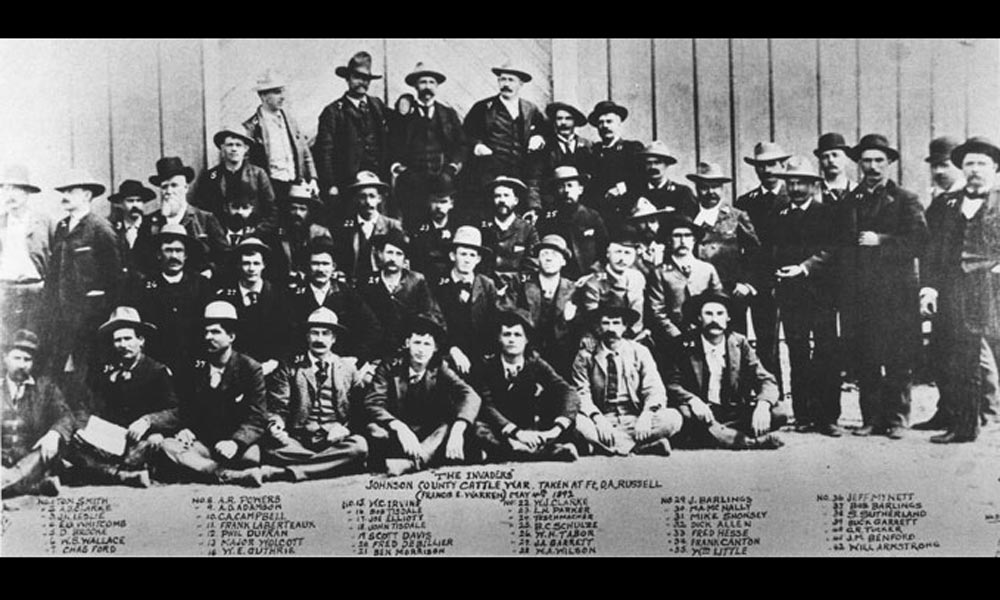

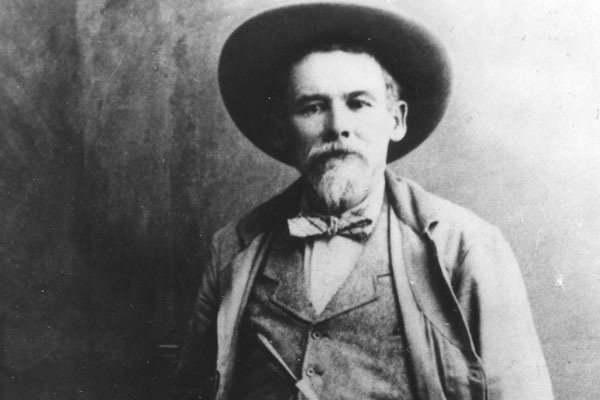

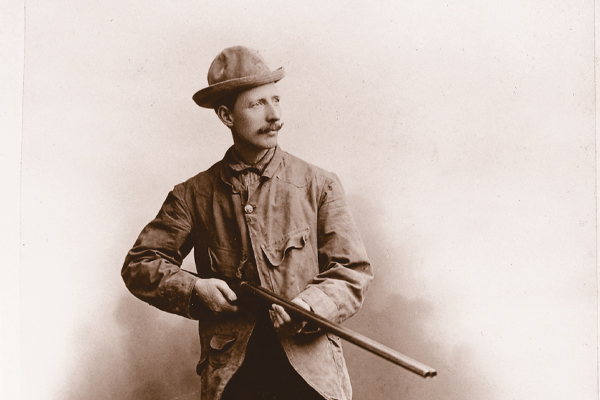

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Emory A. Cantey, Jr. Collection,

– Courtesy Herb Peck, Jr. Collection –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger –

– Courtesy Herb Peck, Jr. Collection –

– Courtesy Herb Peck, Jr. Collection –

– True West Archives –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger –

– Courtesy Phil Spangenberger –