With a Union Pacific mileage book in hand, Frank Tenney Johnson realized his dream to travel the West by rail.

With a Union Pacific mileage book in hand, Frank Tenney Johnson realized his dream to travel the West by rail.

When Johnson saw Pike’s Peak in the Colorado Rockies, he wrote, “The cloud chariots after having circled about the hoary head of Pike’s Peak all the afternoon have silently taken their departure to meet the coming of night.”

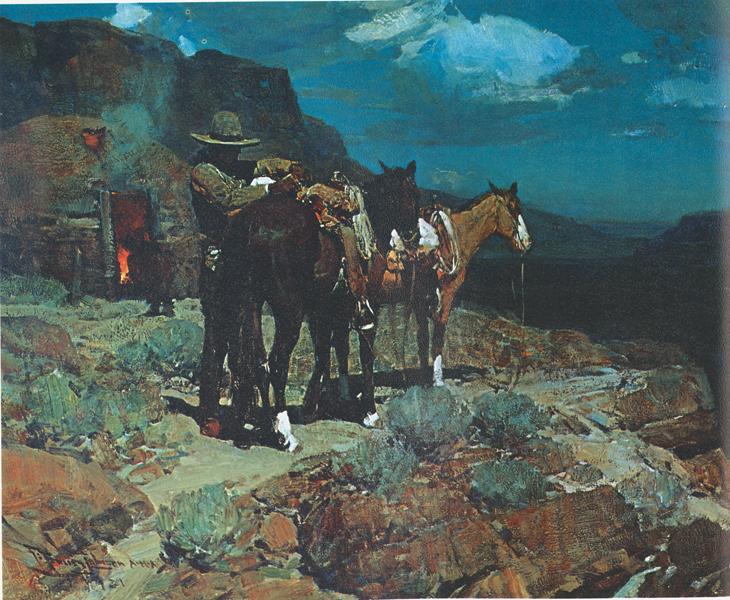

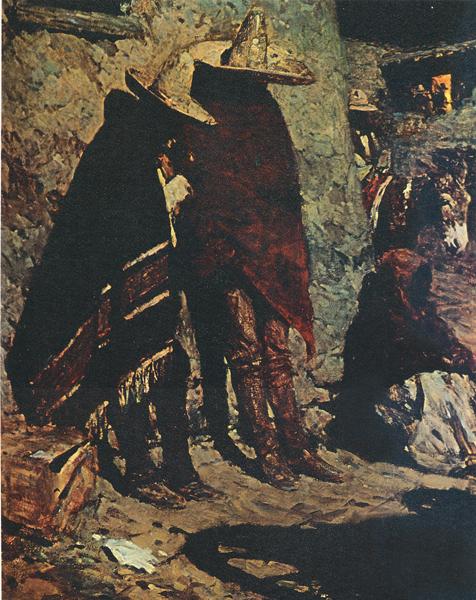

And it was nighttime that Johnson cherished most. His study of daytime colors under the effects of moonlight was realized in his hallmark nocturnes, where he mastered the shifting values of light and shadow.

“Russell and Remington could paint the sunlight,” reported the Los Angeles Times, “but when the twilight shadows began to fall they cleansed their brushes, assembled their canvases and withdrew . . . Perhaps Frank Tenney Johnson is a poet who sings in color. There is a harmony in his canvases that escapes our five senses.”

Progressive Arizona also mooned over the artist, reporting, “An outstanding characteristic of Johnson’s work is his ability to paint moonlight, and in this field he stands preeminantly [sic] alone.”

Johnson’s process may have caught the art critic’s eye. Johnson had a special formula for underpainting a canvas, before he overpainted a nocturne: to the white he added a portion of vermilion, or Spanish red. Then he set the canvas aside for a year, so the underpaint—a smoother base that gives luminosity to a finished work—properly adhered to the canvas.

Or it may have been those 11 nights when Johnson was stranded in Hayden,?Idaho, awaiting the money orders sent by his wife Vinnie. She resided in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, while he toured the West on the railroad book given to him by Field and Stream magazine.

He had spent those nights, camping in rocky canyons and studying how colors were affected by moonlight. He wrote Vinnie about experimenting with colors “the way Maxfield Parrish gets his peculiar techniques.” The deep, extraordinary blues of a Parrish painting were mixed with Johnson’s moonlight studies, marking the beginning of the artist’s nocturne paintings.

When Johnson finally returned to New York City in 1904, he had to pay off the mileage book. His first job for Field and Stream was illustrating “Barb—A Cow Horse,” written by Andy Adams, who had just penned The Log of a Cowboy. The artist’s dues were fulfilled in three months, and he soon began illustrating other publications, including both Harper’s Monthly and Weekly and Cosmopolitan.

When he started painting to his own liking is when Johnson hit the jackpot. Already selling his art to collectors like Dr. Phillip G. Cole, who purchased three of his paintings for $6,000 (Cole’s collection is now in the Gilcrease Museum in Tulsa, Oklahoma), Johnson earned a key commission at the Carthay Circle Theatre in Los Angeles, California. He painted a scene of the Donner party crossing the high Sierras on the theatre’s main drop curtain. Afterward, interest in his art soared.

On April 28, 1937, Frank Tenney Johnson could sign his name with an N.A. afterward, as the National Academy of Design had elected him an Academician, an honor limited to 125 U.S. artists. But it would be a short-lived honor. The following year, while having dinner with some friends, Johnson gave his friend’s wife a sociable kiss. He caught spinal meningitis from her and lived until New Year’s day, when he died at 64.

At Frank’s funeral, his wife wrote, the minister fittingly recited Rudyard Kipling’s poem, “When Earth’s Last Picture is Painted,” for the man who, in his “separate star,” masterfully captured life as he saw it “for the god of things as they are.”

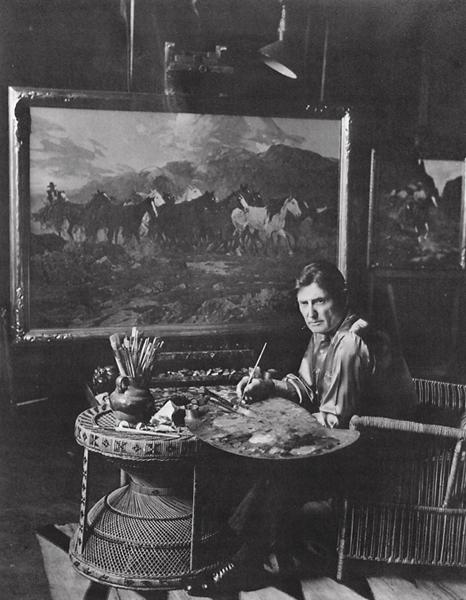

Photo Gallery

– All images True West Archives –