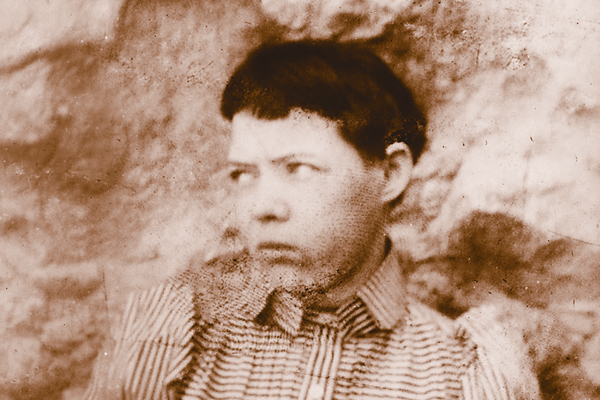

She wasn’t a desperado, but Pearl Hart was desperate when she ambushed her way into the history books in 1899—the only known female stagecoach robber pulling off one of the last stage heists in America.

She wasn’t a desperado, but Pearl Hart was desperate when she ambushed her way into the history books in 1899—the only known female stagecoach robber pulling off one of the last stage heists in America.

They labeled her the “Lady Bandit,” clearly implying she was a pro, even though this was her first arrest. But her story resonated with a country that lusted—then as now—on the naughty. When history looks at her today, she’s a great example of how overblown tales from the West could be.

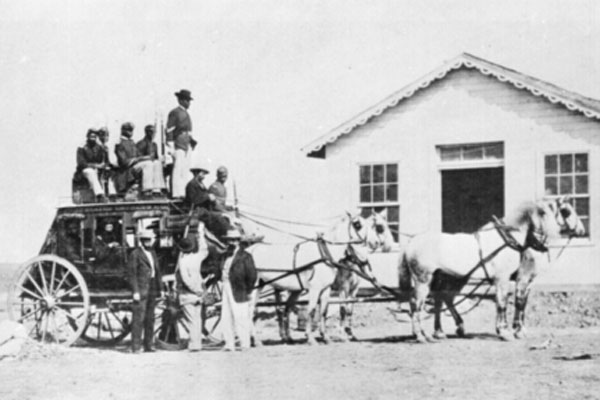

Pearl made her mark near Globe, Arizona, masquerading as a man in a gray shirt and dungarees, with her long hair tucked under a dirty white sombrero and her feet in boots that were obviously too big. It was about five p.m. on May 29, 1899. She and her boyfriend, Joe Boot, had lain in wait in Cane Springs Canyon. Joe stayed on his horse and gave orders; Pearl robbed stage driver Henry Bacon and his three passengers.

The press would eventually try to explain how four men could be so disarmed by a woman less than five-foot-three and under 100 pounds with this excuse: “They were so pop-eyed with amazement that no resistance was offered, even though the driver was armed.” (At least, that’s how Arizona Republic columnist Lowell Parker portrayed it in a 1974 series on Pearl’s life.)

Far more cutting is Pearl’s take on the same situation: “Really, I can’t see why men carry revolvers, because they almost invariably give them up at the very time they were made to be used.”

Pearl would always maintain she resorted to robbery for money to get home to her dying mother in Canada. She and Joe made off with $431.20, Bacon’s Colt .45, a .44 and a gold watch—minus the $1 they left each of their victims so the men could pay for supper that night.

She’d later write a poem about her crime, including this stanza: “While the birds were sweetly singing, and the men stood in a line/ And the silver softly ringing as it touched this palm of mine. / There we took away their money, but left them enough to eat / And the men looked so funny as they vaulted to their seats.”

A bad getaway

These first-time criminals pulled off the robbery with ease, but they had a lousy escape plan. They plunged their old horses into rough country, spending the day lost, and finally emerged on a highway just a mile from the robbery site. The posse didn’t have much trouble tracking them, nabbing them as the couple slept on the ground.

Pearl did her self-serving best to describe the wild ride to escape “from the consequences of our bloodless crime”: “I marvel that we did not lose our lives … Many noises in the great mountains and cañons led us to believe that our pursuers were at hand, but these turned out to be the work of our guilty consciences.”

The captured Pearl quickly realized that being a female robber gave her a special status.

“During her stay in the Florence jail, she became a celebrity, a symbol of ‘contemporary wild western womanhood,’ driven to desperation by love and a dying mother,” notes Days of Destiny, a book by Arizona Highways magazine.

“She saw that boldness paid off and sent a note to the prosecuting attorney: ‘I shall not consent to be tried under a law which my sex had no voice in making.’ The suffragette movement took up her cry, stimulating debate throughout the nation.”

The Winslow Mail couldn’t stand it: “Pearl is the right kind of a woman’s rights woman. She endeavors to practice what she preaches, wears breeches, holds up stages, searched the passenger’s pockets for their valuables … the female suffragists ought to send her to Phoenix to lobby for their hobby during the next session of the legislature.”

And the Globe newspaper found all this hoopla quite exaggerated: “The camera fiends have taken shots of her with all sorts of firearms and looking as much a desperado as they can make her.”

Her celebrity status increased when Cosmopolitan magazine, one of the most popular periodicals of the day, gave her an impressive spread of words and pictures, letting her tell her story in her own words.

It was all a far cry from the haphazard life she’d led her first 28 years—an abused and abandoned wife; a cook; a mother who couldn’t support her boy and girl (they were shipped off to grandma) and bad luck wherever she turned. She was born in 1871 to well-off, religious parents in Canada. She ran away to marry Frank Hart at 16 and left him several times—going back whenever he promised to stop the domestic violence. When she finally left him for good, she was in Arizona and eking out a living as a cook in a miner’s boardinghouse, dating the man who would eventually land her in prison.

Adding fuel to the fire

After Pearl’s transfer to the Tucson jail, she promptly escaped with another inmate who was obviously smitten by her. By now, the Cosmopolitan article was on the newsstands and many papers around the country quoted liberally from it to announce this newest wrinkle in her story.

Pearl and her new pal Ed Hogan got as far as Deming, New Mexico, where a detective recognized her from the Cosmopolitan pictures. Back to jail she went, but it would take two trials to send her to prison.

On November 14, 1899, she appeared in court on the charge of being a stage robber—a crime to which she’d confessed. But her jury voted 11 to one for acquittal. Judge Fletcher Doan berated the jury for ignoring the evidence. Pearl was quickly retried for stealing Henry Bacon’s $10 pistol, and a second jury found her guilty. The judge gave her five years in the Yuma Territorial Prison.

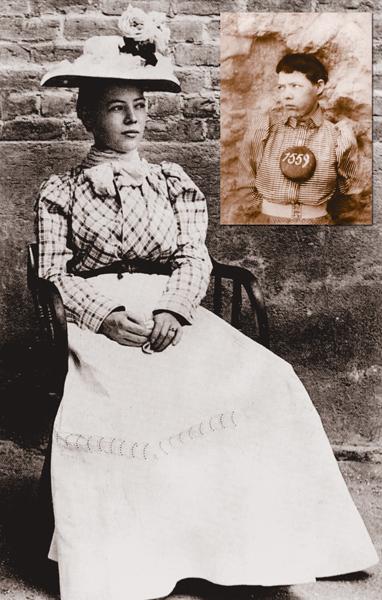

Joe Boot, meanwhile, was handily convicted of the stage robbery and got a 30-year sentence. The robbers arrived in Yuma together, and Pearl put another notch in her celebrity bonnet—she was the only female prisoner.

According to her admission form on file at the Arizona Archives, she arrived in Yuma with $7 in her pocket, a foot size of 21?2 and bad teeth. It says she didn’t drink but did use tobacco and morphine. She was logged in as prisoner number 1559; Joe was 1558.

Pearl’s reputation was all over the board, according to More than Petticoats by Wynne Brown. Some knew her as a good cook and virtuous woman, while others claimed she was a harlot. The files on her life in the Arizona Archives provide no evidence that she was ever a “soiled dove,” but they do attest to her taste for morphine (“hop fiend of insatiable appetite,” as one writer put it). Those who wanted to cut her slack blamed the dope. As prison secretary W.T. Gregory wrote to a friend in 1903: “From her petite, modest appearance no one would suspect her of having the sand to hold up a stage, but I guess she was under the influence of dope when she did it.” (He also described her as “very, very polite … and inclined to be timid.”)

But alas, neither of the robbers served their time. Joe simply walked away after serving less than two years and was never heard from again. And on December 15, 1902, Pearl was paroled by Territorial Gov. A.O. Brodie, released with a train ticket to St. Louis and, by some accounts, “pockets full of cash.”

No one would know for 50 years why the governor had been so generous to Pearl. In 1954, the late governor’s secretary told Arizonan historian and columnist Bert Fireman that they had to get her out of town because she was pregnant. Brown in More than Petticoats claims, “Only three men had been allowed to visit without supervision—and one of them was the governor himself.” If there ever was a baby, there is no record of it.

Eventually, Pearl returned to Arizona and married Globe cowboy Calvin Bywater. She lived “the quiet life of a hardworking, stout ranch woman,” reports Brown, noting Pearl was last sighted in Globe about 1957, when she would have been 86 years old. When she died and where she’s buried are unknown.

But history won’t soon forget—even in its overblown version—the Lady Bandit.

Photo Gallery

– Pearl Hart courtesy Arizona Historical Society; Mug shot courtesy Arizona State Library, Archives and Public Records, Archives Division, Phoenix, #97-8677 –