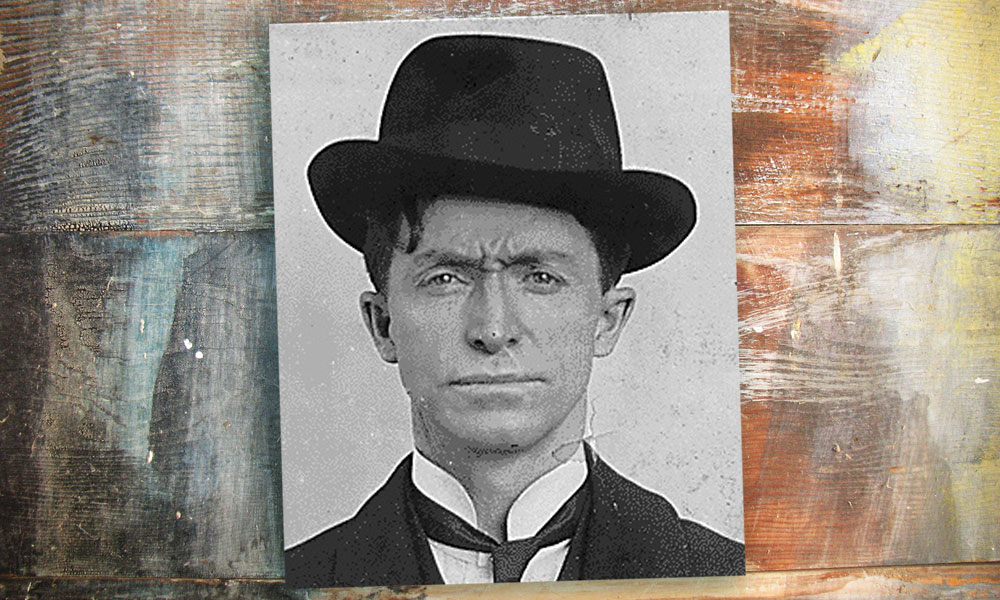

He did not wear a mask or carry silver bullets.

The Virginian was designed to be the first Mystery man of Old West fiction.

He did not wear a mask or carry silver bullets, but he has managed to survive for more than a century without ever once revealing his real name. We know more about the Lone Ranger’s backstory than we do the hero of Owen Wister’s best-selling 1902 novel, who only admits to being 24, well-traveled in the West and from Virginia.

While far from being the first book set in the American West, The Virginian is the novel that defined the character of the American cowboy (“When you call me that, smile.”). The book serves as a primary reference for generations of stories, up to and including Larry McMurtry’s “Lonesome Dove” series; Wister’s character Steve clearly informs Dove’s Jake Spoon.

The popularity and quality of the novel explains why it’s been so frequently filmed, beginning with Cecil B. DeMille’s 1914 adaptation; followed by another in 1923; the most famous, starring Gary Cooper, in 1929; another, featuring Joel McCrea (who was too old for the part), in 1946; and, more recently, a made-for-TV version in 2000 with Bill Pullman and Diane Lane. In each of these versions the character and events are essentially unchanged. Wister nailed the story out of the gate—in much the same way that The Virginian ropes a feisty pony in the very first paragraph of the novel.

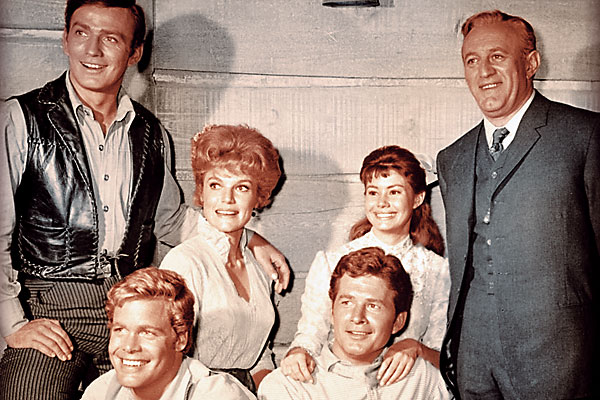

Modern audiences are familiar with another adaptation: the TV show, The Virginian, which endured for nine seasons, from 1962-71. What most distinguished The Virginian from all other TV Westerns was its length; each episode was 90 minutes long, which, after commercials and including credits, measures roughly 75 minutes per show. In essence, each show ran the equivalent time of your average B-Western feature.

To make The Virginian work as episodic television, the writers had to make a few essential changes to the story, in order to create a core set of characters who could remain intact from one episode to the next. For instance, in every filmed version of the novel, The Virginian’s nemesis was the character Trampas, who is killed by The Virginian at the conclusion of the story. Yet in a TV series, a central character can’t kill his literary enemy in the first show. Nor can he have a single romantic interest, Molly Wood, like he does in the book—not if he wants to share screen time with hot, series-hopping, ratings-boosting Hollywood ingénues from one season to the next.

The writers kept Trampas (Doug McClure) but bleached his villainy, making him The Virginian’s roguish pal. Trampas’s friend Steve (Gary Clarke), who is hanged for rustling in the story, becomes his third cowbuddy. Molly (Pippa Scott) fared less well. The series transformed her from schoolteacher to newspaper owner to, well, dead. Molly lasted only seven episodes before exiting the series altogether. (Westerns fans best remember Scott as Ethan Edwards’s murdered niece Lucy in 1956’s The Searchers.)

In the part of The Virginian the show cast James Drury, a handsome and personable actor who had learned horsemanship as a tot on his mother’s family ranch in Oregon. After studying acting in New York (his father was a professor of marketing at NYU), Drury had been bouncing around Hollywood in small-medium movie roles and various TV series for a handful of years.

At the age of 28, after just wrapping a part as one of the vile Hammond brothers in Sam Peckinpah’s 1962 movie Ride the High Country, Drury was just about perfect for the part. Drury had the exact amount of authority the character of The Virginian required to assure audiences he was capable of assuming top hand responsibilities in a spread as big as the Shiloh Ranch. Drury had also played the part in a 1958 one-off pilot version of the story, when, interestingly, he was the actual age of the character in the novel. The show remembered Drury when it came time to look for the lead.

Drury is the man who can best attest to the devotion of the show’s fans. He continues to meet with his fans at events all over the country. When we spoke to him, by phone, he was preparing for his appearance at an annual celebration of William Boyd and his character Hopalong Cassidy in Boyd’s hometown of Cambridge, Ohio. In fact, the event was hosting a Virginian reunion, where fellow cast members Gary Clarke, Roberta Shore and Randy Boone were joining Drury.

True West: Is it true that your first major success as an actor came when you were eight years old, playing a man in his seventies?

Drury: I was in a Christmas play about King Herod and the Christ child. I played King Herod with a great flowing beard and long robes. I hit my marks, and said my words, and I knew them all. When it was over, people clapped. That was a new experience for me. I didn’t believe that I could make someone applaud me for doing what I’d done. I thought, “Well, if I can get ’em to clap for something like this, I’ve gotta learn more about it.” So I just stayed with it all the way through junior high, high school and at New York University, which had an excellent Shakespearean program at that time. We were trained as classical actors.

I came back out West for a vacation when I finished my junior year, was in Los Angeles for seven days and got a contract at MGM in 1954. I kept going and growing and kept learning. When I was 26 I was signed to Universal for seven years. I had no idea they had The Virginian in mind [for me], but apparently they did. They kept screen-testing me and telling me I was too fat, so I lost 30 pounds in 30 days.

Where did you work prior to the show?

One of the first jobs I had at MGM was to appear in a picture called Diane with Lana Turner and Pedro Armendariz, where he was King Francis I. I had to play a palace guard, standing around with a helmet and a spear. But I was on horseback quite a few times in the picture, and they saw that I could ride. I’ve been on horses since I was in diapers, on my grandfather’s ranch in Oregon. From then on, most of my acting career was done from the saddle. I had expected to do important, serious work…. Once The Virginian came along, it just cooked my goose as far as being a Westerns actor….

I can do many other things; I haven’t had much of a chance to do them. Still, I just turned 76, and [Sir John] Gielgud was working when he was 95, so I think there’s hope for me yet. The point of the matter is, if you can play Shakespeare, you can play anything.

The theatre brings to mind how uneasy Broadway veteran Lee J. Cobb, who played Judge Henry Garth, felt acting in the series.

That’s right. And he was making an awful lot of money on the show, more money than he’d made in a long time. He was absolutely responsible for us to be able to go into production on The Virginian. Because of his name and his status as an actor, they didn’t even require us to make a pilot. We just started making the shows. This was a tremendous gamble, because it was the first 90-minute show with continuing characters. Most people didn’t think we could do it….

But Lee was really frustrated; he wanted to do more important things. He once gave an interview where he said, “If I had the money, I’d buy up all this film and make banjo picks out of it.” He had to come to work the next day, after the interview appeared, but we loved him and kidded him about it. Of course he did eventually leave. I was able to see him do King Lear, and he was wonderful.

What happened with Charles Marquis Warren, who was originally slated to produce the TV show, but was replaced by Roy Huggins and others?

He was great, and he had a great concept of the show, but, you know, there’s nothing like success to bring out people that want to tinker with that success. That’s all I can really attribute anything to. They just decided that he had maybe too much power or maybe he was too much—I don’t know. They certainly didn’t check with me….

Basically, the show had a life of its own, and we survived the producers that they gave us. No matter what happened, we survived, because the show had such a great central core of characters. And we had this marvelous ability to attract major actors and actresses because of our 90-minute format. We had big, big parts for those people, not big parts for an hour show, but big parts for an hour and a half, and that’s 71 minutes and 30 seconds worth of film!…

Charles was treated badly and was kind of run out on a rail for no good reason. He produced the George C. Scott episode [“The Brazen Bell”], for God’s sake.

What’s the story behind you and the Chapman Crane, which was used to elevate and move the movie cameras?

They kept trying to cut the budget, cut things down, cut down the amounts of times we could use special equipment like a Chapman Crane.

I became very, very difficult about that. I just went home. When you go home in the middle of the day, when they’re shooting down there, it pisses a lot of people off. They’d say, “Well, what are you doing at home? We’re shooting a picture here.” I’d say, “Give me the Chapman Crane back, which was written in the script, then I’ll come back.”

The Chapman Crane would come back in, because that’s what my cameraman wanted, that’s what he said he wanted, told me he wanted, so that’s what he got.

Did you enjoy having that much clout?

Well, they couldn’t do it without me. They tried, but they couldn’t do it. That was just they way it worked. I certainly could have been a lot nicer about it, but if I had, I wouldn’t have gotten it done. That’s the other side of that coin.

I never raised hell about anything except quality. That’s the only thing I was interested in. And I just tore ’em a new one every time they tried to cut the quality. As you can see, we had a great show for nine years.

I believed in the concept of the show so much, and so fervently, I knew how it was going over, because it was a show of great quality. “But we can’t spend this much money on this show.” Well, they were spending $330,000, I think, per show in the first season, and they wanted to cut the budget by $30,000. I wouldn’t stand for it. So by spending $330,000 on the second season and the third season, they began to net $1 million an episode, as it showed … and that’s after everything was paid for…. At the end of the nine years, 260 or 270 shows that they admit to (I think there were 296, but hell, I was only there; I don’t know), no one will admit to that…. So who was the crazy one? [Laughs.] Who was the bad guy?

It’s so silly, because spending $330,000 to net $1 million is a pretty good deal in anybody’s economy. Anyway, we got it done. At the end of the nine seasons, I tipped my hat, and we parted ways, and I haven’t worked at Universal since. Not one time in 48 years. It’s okay. I got what I wanted. [Laughs.]

Do you really believe anyone from the show is holding a grudge against you?

I think we finally got the DVDs released because all of my enemies finally died off. [Laughs.] But they weren’t going to give up on being mad at me for a looong time.

Did you get your resistance to authority from your mom or your dad?

Actually from resisting everything my mom wanted me to do. She wanted me to become an actor, and I didn’t want to become an actor. She booted me on stage and made me play King Herod in that biblical play for children. Then they clapped, these people clapped, and here I was, eight years old, deciding that that’s what I wanted to do for the rest of my life.

She wanted me to only associate with the best kind of people. I wanted to go out with the kids who were smoking. I started smoking when I was eight years old, and I started drinking when I was 12. All these things were very, very bad from my mother’s point of view. I just enjoyed doing them because it made her mad!

I always was a contrarian. I got expelled from high school on the day before graduation for hollering in an assembly. A friend of mine was getting an award, and I was hollering, giving him kudos, you know. The monitors came down and cornered me, and took me to the vice-principal. He kicked me out of school. So I sat in the audience the next day, while all my classmates graduated, and smoked a cigar.

It’s a life of defying authority, and I never changed a thing. It got me where I am today—at the Hopalong Cassidy Celebration. Here I am, and people have come from all over for our pictures and DVDs. I couldn’t be more thrilled.

Speaking of defying authority, how did you hook up with Sam Peckinpah?

The first time I worked with him was on an episode of Trackdown [1957-59 CBS series] with Robert Culp, which he had written and was directing. [Peckinpah] was appreciative of what I did on the show…. We remained friends and became drinking buddies.

When Ride the High Country came up, I understood or had heard that he wanted Bob Culp for the part. Bob didn’t want to do it, because he didn’t want to be perceived as a heavy, as a villain. His whole persona at the time was to be heroic. My persona at the time was to grab the part and play the hell out of it, and not worry. Let the chips fall where they may. It was a labor of love for me, and I had the greatest bunch of cutthroat mountain brothers you could ever put together, with L.Q. [Jones], Warren Oates and John David Anderson. They all played their lascivious best, and we just had a ball with it. I thought, “We’re a great counterpoint to Joel McCrea and Randolph Scott, the heroic figures.”

Of course Sam’s direction was imaginative and inspired in every way. He had so many great ideas that he put together in that movie. It all just came together like a great recipe. It’s one show that I’m really proud of. I loved every minute of it, and I’m so happy that Bob Culp didn’t want to do it! [Laughs.]

In The Virginian, didn’t you work with two actors, Ben Johnson and Brian Keith, who also worked with Peckinpah?

We did a movie for Disney called Ten Who Dared, where I played the brother of Maj. Wesley Powell, the guy who Lake Powell in Arizona

is named after. There was a fight on the water with Ben Johnson and Keith and I, and I’m telling you, the only thing keeping that water we were in from turning to ice was that it was moving too fast! It was the coldest water that I felt in my life.

Sam went on to make The Wild Bunch and all that; a bunch of those people like L.Q and Warren Oates, who were in Ride the High Country, got to go on and work with him. But I got cast as “The Virginian,” and I didn’t get to do any more Peckinpah pictures, which I always regretted. I wouldn’t really have traded The Virginian—I thought it was the better course of action.

All in all, I guess I’m one of the luckiest men who ever lived, and I’m still alive and vertical. When I get up in the morning, that’s the main thing. My grandfather used to say, “You have to take the bitter with the sweet.” [Laughs.]