Trails across the West in the mid-1800s crisscrossed Indian lands, often displacing the people who had been living on the land for generations. The Bozeman Trail is no exception. It cuts through some of the prime hunting grounds for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Crow tribes and was hotly contested as a result.

Trails across the West in the mid-1800s crisscrossed Indian lands, often displacing the people who had been living on the land for generations. The Bozeman Trail is no exception. It cuts through some of the prime hunting grounds for the Lakota, Northern Cheyenne and Crow tribes and was hotly contested as a result.

In most cases, the trails permanently displaced wildlife and people. But in an unusual turn of events, the Indians successfully defended their rights to the region marked by the Bozeman—at least for a while longer.

The route was a shortcut, which may have been part of the problem for those who used it. (Remember what Virginia Reed said about shortcuts after her family became stranded with the Donner Party during the winter of 1846-47: “Never take no cutoffs and Hurry along as fast as you can!”)

John Bozeman’s name is attached to the route that branched away from the main Platte overland road to provide access to Montana goldfields. Bozeman and John Jacobs scouted the road in the spring of 1863, traveling from western Montana, where gold had been discovered in Alder Gulch. The yellow metal was the catalyst for the trail. Bozeman knew people coming from the East would want to reach the new diggings as quickly as possible. His diagonal trail across Wyoming and Montana promised to spur development.

Bozeman and Jacobs organized a wagon train in early 1864 and headed out on their new trail. They departed from Deer Creek Station (near Glenrock, Wyoming), but barely made it 140 miles when a war party of Lakota and Cheyenne Indians changed their plans (they returned to the main overland road closer to the Platte).

That interaction with the tribes was the portent of what would come for travelers along the Bozeman, although some 1,500 travelers took the route in 1864 and more would travel it over the next four years.

Connor Bloodies It Up

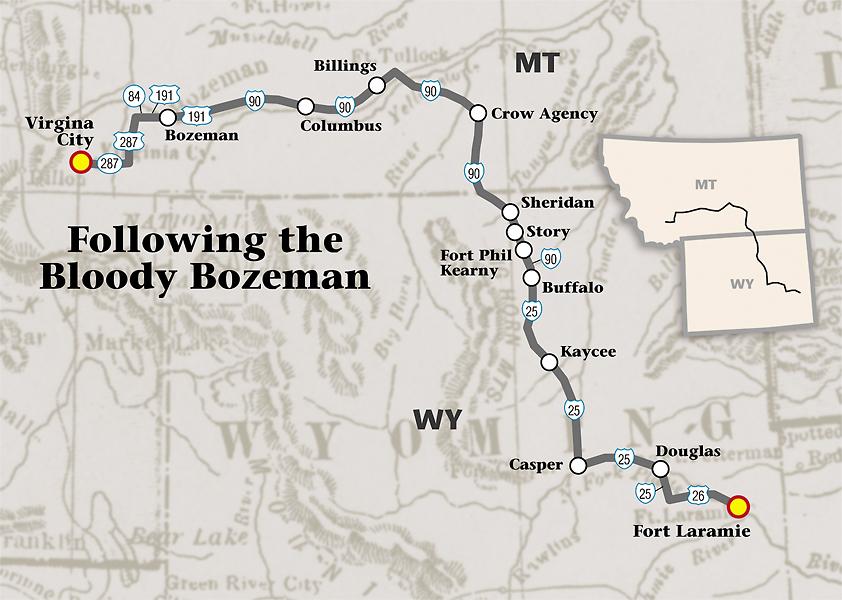

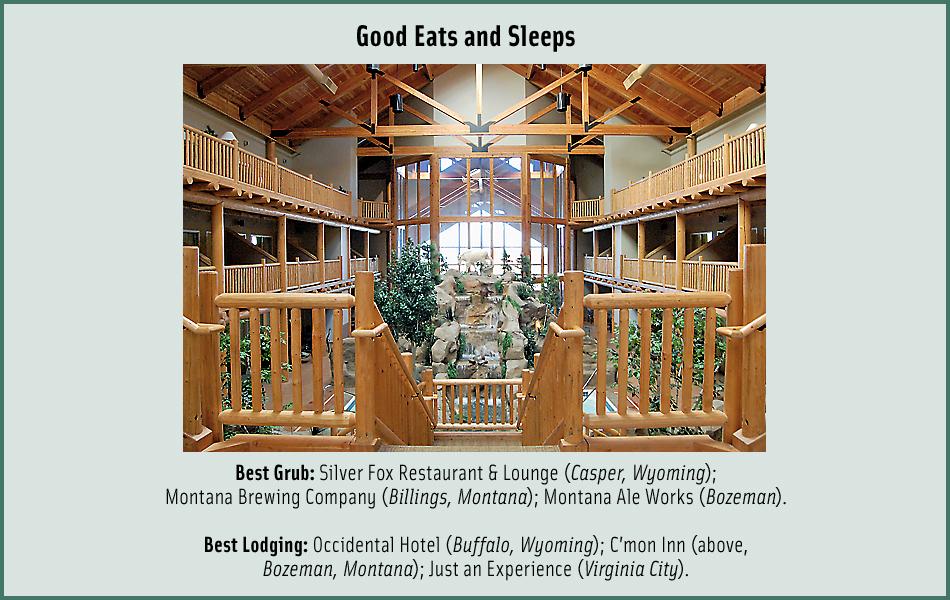

The best place to start a road trip tour of the Bloody Bozeman is at Fort Laramie, an important trail outfitting point that also served as a military fort.

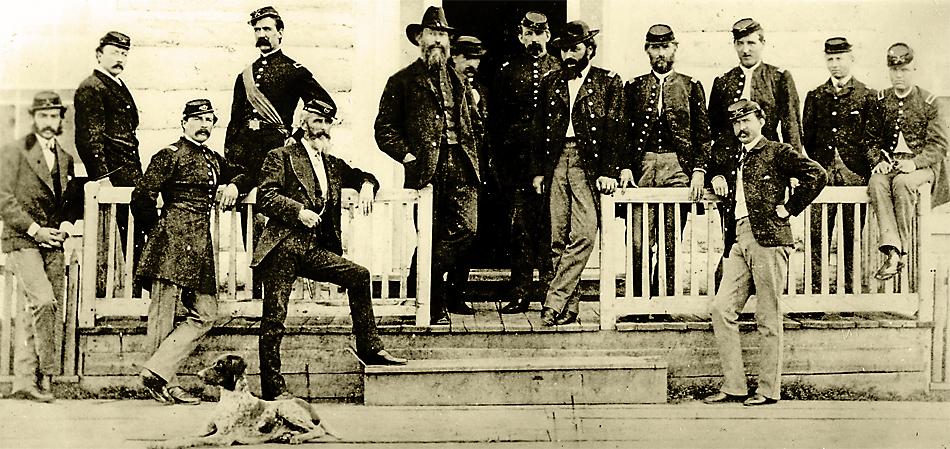

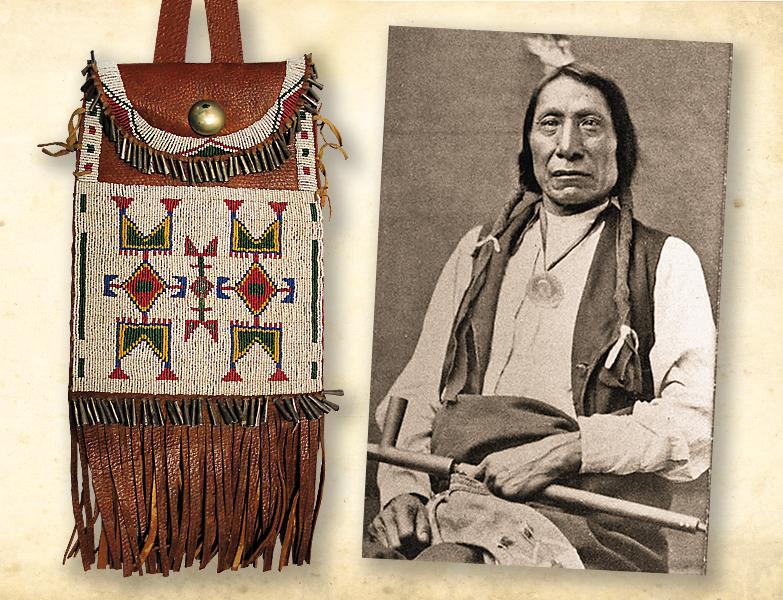

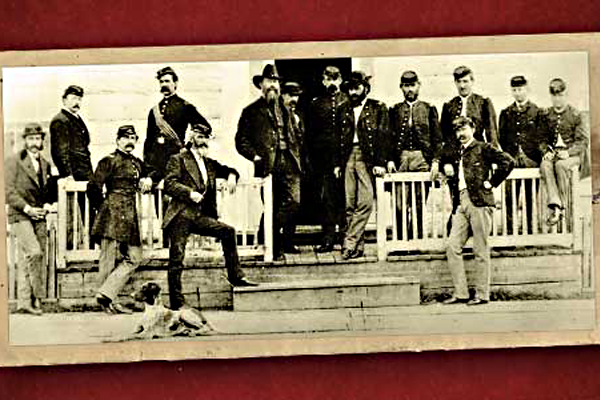

In 1865, Patrick Connor led a military regiment that attacked an Arapaho camp in northern Wyoming. This led to a peace conference, held at Fort Laramie in 1866, to negotiate a treaty with the tribes to allow safe passage through the Powder River Country. Red Cloud attended as one of the primary leaders of the Lakota tribe. The government’s cocky attitude, however, led to the arrival of Col. Henry B. Carrington and 700 troops, who reached Fort Laramie before the peace conference concluded. Red Cloud departed, as he and other Indian leaders believed the government had been duplicitous—negotiating on one hand, while bringing troops to enforce any agreements on the other.

The Indians vowed they would hold Powder River Country, further setting up conflict along the Bozeman Trail.

Heritage of the Displaced

From Fort Laramie, the Bozeman Trail branches away from the North Platte River in two locations between Douglas and Casper. Some of the troops who patrolled along the route were headquartered at Fort Fetterman near Douglas.

Troops stationed at Fort Caspar in Casper protected transportation lines along the North Platte River. Established in 1862 as Platte Bridge Station, the fort was renamed following a fight in July 1865 with Lakota and Cheyenne warriors, during which Lt. Caspar Collins and other soldiers were killed. The post remained in use for another two years until it was abandoned. Fort Fetterman replaced Fort Caspar.

Fort Caspar is managed by the City of Casper, with replica buildings and a visitors’ center. “Colors on the Plains: Northern Plains Indian Decoration,” a new exhibit in place until November 2,features decorative work of tribes from the Northern Plains, including moccasins, toys and weapons made by Lakota, Cheyenne, Shoshoni and Arapaho peoples in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

After a stop at the National Historic Trails Interpretive Center in Casper, continue to Kaycee, home of the Hoofprints of the Past Museum, and then to Buffalo, for a tour through the Jim Gatchell Memorial Museum with its impressive collection of vintage wagons and Indian artifacts.

Red Cloud’s Trap

Heading north, the Bozeman Trail crosses open country, much of which is now ranchland, to Fort Reno, one of three frontier posts established to provide protection for travelers. The second of those posts, Fort Phil Kearny, sat 14 miles north of present-day Buffalo, and it became the central hub for the soldiers. Located along the east flank of the Big Horn Mountains, Fort Phil Kearny was in the heart of tribal hunting grounds, making it strategically placed by the military and strongly opposed by the Indians.

After visiting the re-created Fort Phil Kearny, travel north, crossing Lodge Trail Ridge, just like Lt. William J. Fetterman did along with 80 of his fellow soldiers. In December 1866, the troops rode into a trap laid by Red Cloud. Before the fight ended, Fetterman and all his men lay dead upon the hillside.

Commander Carrington sent relief riders, including civilian Portugee Phillips, down the Bozeman to Fort Reno and ultimately all the way to Fort Laramie with an urgent request for additional troops. The military complied. By summer of 1867, tension was rising along the Bozeman route, and the vicinity of Fort Phil Kearny saw more conflict.

A peace commission held in early 1867 at Fort Laramie was unsuccessful; the frontier Army refused tribal demands that the forts and the troops serving at them be removed. In August, tribal warriors staged a series of coordinated attacks along the trail. One involved a party of woodcutters, who took cover behind their wagons in an engagement that became known as the Wagon Box Fight. A rural road up Piney Creek leads to the site of that battle and to the small town of Story.

In Ranchester, along the Tongue River, you’ll find the Connor Battlefield, the site of an 1865 attack on an Arapaho camp by Col. Patrick Connor. Troops under Connor destroyed some 250 lodges and killed many of the Arapahos, including women and children.

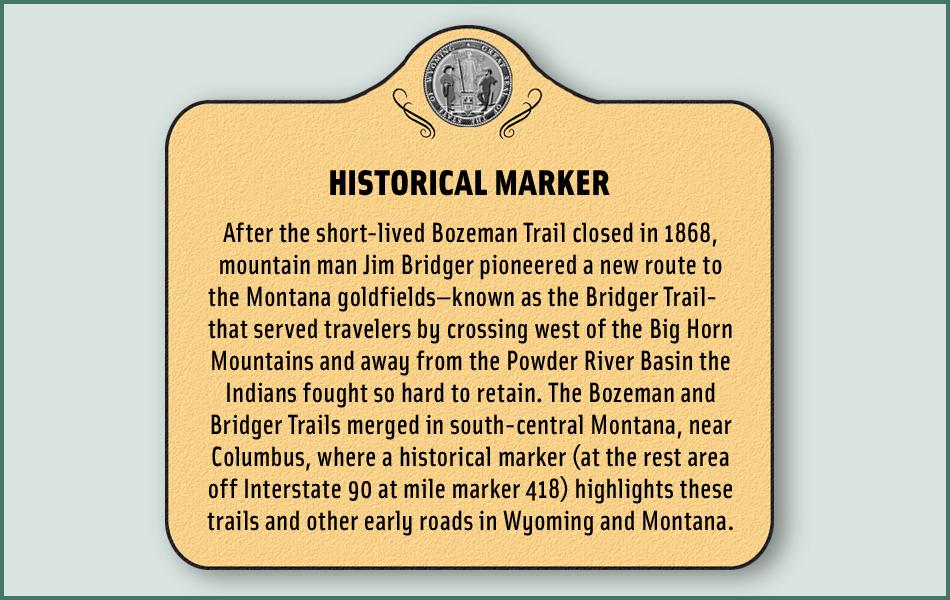

Fort C.F. Smith, the third key military post along the trail, was beside the Big Horn River at the Spotted Rabbit Crossing. Much of this portion of the trail is across the Crow Indian Reservation. Yet Lakota and Cheyenne tribesmen, not Crow, coordinated attacks in early August 1867 to battle troops from Fort Smith in what became known as the Hayfield Fight. Although you can take a series of back roads to remain close to the trail when traveling from Ranchester to Columbus, Montana, I stick to the Interstate.

The events around Fort Phil Kearny and Fort C.F. Smith during 1866 to 1868 were part of Red Cloud’s War. The tribesmen scored one victory after another and found ultimate success when the Army closed the Bozeman Trail forts. After the soldiers withdrew, the Indians burned the posts, bringing to an end the conflict subsequently called Red Cloud’s War. With other leaders of the various Indian bands, Red Cloud, victorious in forcing the military to abandon the Bozeman Trail forts, returned to Fort Laramie and agreed to the terms of the 1868 Fort Laramie Treaty, which established the Great Sioux Reservation.

Battlefields to Goldfields

For the next eight years, conflict was minimal, but in 1876, unrest erupted again during the period that became the Great Sioux War. More battles broke out in the Powder River Basin, including the fight at the Rosebud, involving troops commanded by Gen. George Crook and Indians led by Crazy Horse and others. The most important battle of this war took place along the Little Big Horn River (or Greasy Grass), near Hardin. This is the battle that led to the death of George A. Custer and many of the men who rode onto the battlefield with him.

Like the battles and most of the skirmishes of Red Cloud’s War, theIndians also struck a hard blow against the military at Little Big Horn. Each June, around the anniversary date of the battle—June 25—a re-enactment takes place at Little Bighorn Battlefield. At the site, you’ll find not only memorials to the soldiers who died there, but also a monument to the Indian combatants.

All of this conflict during Red Cloud’s War, which caused the deaths of soldiers, Indians, freighters, emigrants and gold seekers, resulted in the Bozeman Trail becoming known as the Bloody Bozeman.

But let’s not forget, the trailblazers created it as a route to the goldfields. So let’s continue the journey from Billings—where the Yellowstone County Museum has displays of Indian clothing, weapons and paraphernalia—west to Bozeman. This city named for John Bozeman is home of the Museum of the Rockies, known for its paleontological collection, but which also has a collection of Indian artifacts worth seeing.

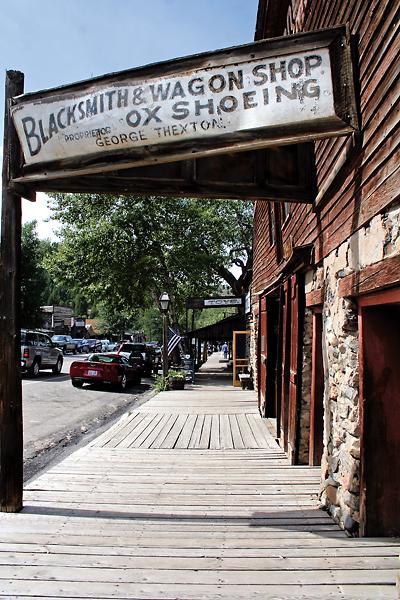

Southwest is Virginia City, the site of the Alder Gulch gold diggings that impelled the trail Bozeman pioneered.

Now a National Historic Landmark, Virginia City is a place where you can buy some good period duds at Rank’s Mercantile (still in its original 1864 location), have a drink at the Bale of Hay Saloon or attend a 19th-century melodrama at Piper’s Opera House, rebuilt in 1885 after a fire. Just west of Virginia City stands Nevada City, a “new” town built of historic structures from across Montana. Here, you can pan for a bit of gold yourself.

In use only for a few short years, from its beginning in 1863-64 to the destruction of the military forts in 1868, the Bozeman Trail did allow gold seekers an opportunity to travel a short, albeit hazardous, route from the Platte to Alder Gulch.

Candy Moulton is the author of Valentine T. McGillycuddy and Forts, Fights and Frontier Sites: Wyoming’s Historic Sites. She’s traveled much of the Bozeman Trail by wagon train.

Photo Gallery

– All photos by Candy Moulton unless otherwise noted –

– True West Archives –

– Red Cloud photo True West Archives; Lakota dispatch bag courtesy Fort Caspar Museum –

– Courtesy National Park Service –