There’s something comforting about being on Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch, up in Newhall, California.

There’s something comforting about being on Gene Autry’s Melody Ranch, up in Newhall, California.

Passing through the gate and onto the lot, there’s a real familiarity to the place, even if the boulders are hollow, affixed in the back with crossed timbers, and the ancient, broken steer skulls that mark the signs are barely held together by wires.

Boomers like myself were in some ways raised here, the place where Matt Dillon, Hopalong Cassidy, the Lone Ranger and dozens of other cowboy heroes pulled themselves out of jams and scrapes, wrestled right from the clutches of wrong and fought the good fight in a world of moral absolutes.

A fair amount of America’s innocence is to be found on these few acres of prime California real estate.

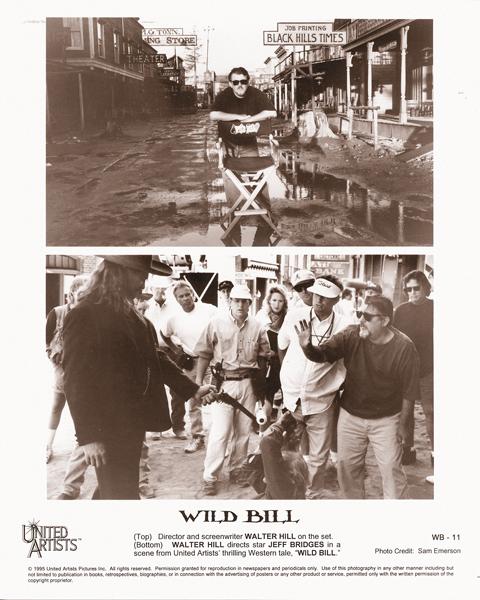

On the set of Deadwood

These days, however, the Melody Ranch is home to the HBO series Deadwood, and in the middle of all that hallowed ground, a complex epic story is being played out, one that tests the limits of those older, crayola-colored Westerns and re-examines the simple tropes of the frontier drama.

Most folks who have any familiarity with the Old West know Deadwood, South Dakota, as the place where Wild Bill Hickok met his unfortunate end, holding a poker hand that legend says was two pairs, aces and eights. Whether that fifth card was ever dealt has never been determined, but it’s an indisputable fact that Jack McCall put a bullet through Hickok’s head in August of 1876, just as the town was getting settled.

Leslie Martinelli, HBO’s PR rep, tells me that when she first started bringing people onto the set, there were only three or four original buildings on the strip that represents Deadwood’s main drag.

“There was Al Swearengen’s Gem Saloon, the Bella Union and the Grand Central Hotel. That was it,” she says. “The town here has grown along the same lines as any boomtown might have at the time.”

As we tour the deserted streets and the ramshackle, replica 1876-era buildings, there’s an eerie Twilight Zone quality, as if the local inhabitants have been secreted off by the Muranians who once lived in the Phantom Empire beneath Autry’s ranch. The occasional jet passes overhead, which only adds to the surreal flavor, and I’m told that shooting is often halted because of the noise the planes make.

The street itself is designed to resemble a market as much as it does a boulevard, a place where strolling customers might find food, tools and the common wares and services available to the visitors and transients at that time. A gutted deer lays on a slab outside the butcher’s shop; fruits and vegetables are laid out on makeshift stands.

Inside an empty saloon, the quiet room seems a bit like a cathedral, with its high ceilings, dim lights and antique colored bottles. The gambling tables are silent and the roulette wheel doesn’t actually spin. What’s missing, besides the customers, is the smell of cheap tobacco, whiskey and desperation.

In a separate soundstage behind the street, Doc Cochran’s office is filled with a variety of herbs and medicinal plants, hanging to dry from the low ceiling. Doc Adams’ place (in Gunsmoke) never looked this funky, that’s for certain.

And, of course, no trip to Deadwood would be complete without a visit to Carl Mann’s Saloon #10 and the table where Hickok was slain, largely due to fellow poker player Charlie Rich taking Hickok’s customary back-to-the-wall seat, which he imagined would irk Hickok enough to give Rich a slight advantage in the game. It was a ploy that haunted Rich for the rest of his life, by all accounts.

Hickok (played by Keith Carradine) exits the series when he dies at the end of episode four, but his legacy and his death inform much of what happens in the shows that follow. “Hickok was a prodigious, f——athlete and out of his mind, what we would now call bipolar,” says David Milch, producer and chief architect of Deadwood. “He could not sit still, couldn’t sleep, and as long as the nation had a purpose for him, as a scout or soldier or marshal, they could put his energy to use. But then they turned him into a caricature and ate him—put him into vaudeville, and when they were done, he finally consumed himself.

“There’s a wonderful letter—Hickok’s last letter—which he wrote to his wife of a week, and which moves from person to person in the course of the second season of the show, eventually finding its way to millionaire George Hearst’s geologist, who I’ve named Samuel Wolcott. In our story, Wolcott is a sexual sadist and killer, and he’ll be played by Garret Dillahunt, who played Jack McCall, Hickok’s assassin, in the first season.

“So, in a sense, the guy who kills Hickok winds up as another character who is the recipient of his legacy, and who becomes fixated on him,” Milch says.

Continuing the tour, off to the back of the strip, there’s a Chinese alley, with signs written in Asian script. Exotic roots and foods are laid out in bowls, and clothes are hanging outside the laundry. And at one end is the pig pen that those who know the show will recognize as the place where bodies are routinely disposed of.

One of the things that defines Deadwood is the similarly organic nature of the show itself, which Milch claims is to some extent made up as they go along.

“It’s not as though there isn’t a sense of structure, but there is a constantly evolving aspect to the show, just as there was to the town itself,” Milch says. “The thing is, I’m blessed, truly blessed, with a cast and crew who thrive on the kind of improvised nature of the thing. I never plan the scenes. If I can identify what the tension is between two characters, then I can just let it go.

“I have a very broad idea of what the events that ought to occur are, but I don’t think of them in sequence. We just, two days ago, changed everything. It’s of the essence to be ready to be surprised. As they say, visions come to prepared spirits, and I’ve spent a long time learning how to be prepared. I come to this show with a lot of craft, which makes it possible to change things very quickly, move things around. I know how to do all that stuff.

“But having developed all that craft, I feel that I need to submit myself to the moment and see how I can serve, be of service to the moment,” he adds.

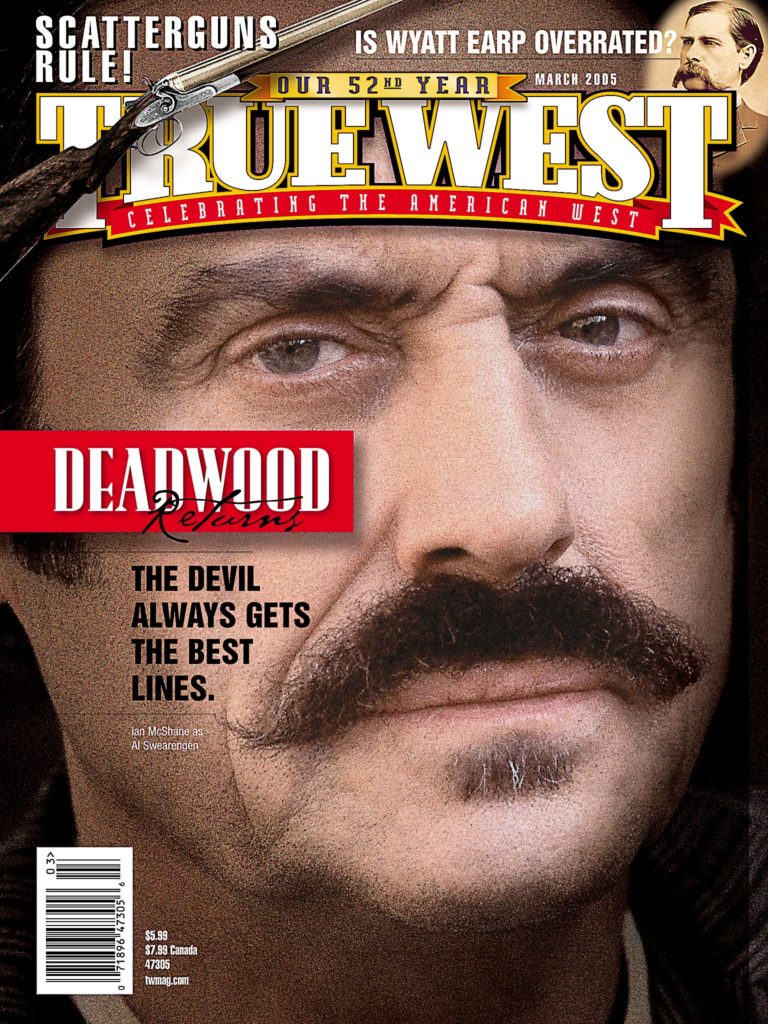

British-born Ian McShane, who plays Al Swearengen, one of the primary forces in the burgeoning town, says of Milch’s approach, “We never know what scene we’re going to do until the night before. I know that Milch has the overall plan in his noggin, as do the writers. And that works. And how many times can you say that you can go into a series—we’re on our—what?—19th show?—and I don’t think I’ve changed so much as a comma, much less a word or a line. A show like this, you just say the lines and the rest will take care of itself. And no one here gets away with anything. You’ve got to come in knowing your sh–, or else you’re in deep sh–.”

At home in his character

To its credit, Deadwood is not a show that is particularly accessible to viewers who might drop in for two or three episodes, trying to get an overall sense of who the characters are or what the story is about. Like similar shows produced for HBO that include Carnivàle and The Sopranos, the series has its own sense of scope and purpose, and it’s only over a stretch of ground that the real heart of the drama begins to emerge.

“What Deadwood is about, is really America,” McShane says. “It’s about the rise of capitalism, and the way that government, alliances, bureaucracy, evil, all evolve—it’s really a saga. There’s not been anything like it. You talk about Unforgiven, the great Westerns, My Darling Clementine, the Ford films that all have their moral vision and their clarity. Deadwood is something else.”

To a great extent, it’s McShane’s sly-eyed Al Swearengen who sits at the heart of the unfolding drama. Best known for his starring part in the British series Lovejoy, his marriage to Sue Ellen Ewing on Dallas and his work in the recent feature Sexy Beast, McShane is as much at home playing Swearengen as Swearengen is at home on his balcony in Deadwood, where he can often be found of late, surveying his town and the people who live there.

“Swearengen is the most aware character in the series—he f—- up, and he knows he’s f—– up,” says McShane, lighting an unfiltered Lucky Strike. “He’s not at peace, God knows, with his torturous background, but he’s at home in his own character, which is more than you can say about most of the other characters.

“You rarely get to play someone who’s as complicated as Al is but also simple at the same time. He is the smartest guy in town. And as the show has progressed, Al is becoming less and less a villain, and we’ll see that the hat, the hero figure, Seth Bullock, is not so simple either.”

It’s also clear that Swearengen is closer to Milch’s heart than probably any other character in the series.

“Well,” Milch says, “the devil always gets the best lines. Seriously, though, for me, that’s the human story. Any story is simply an account of how an individual bears in the present the distorting weight of the past, and some men and some women are very heroic in the way they carry their weight. And the more weight they carry, if they’re heroic, the more they accomplish. Some people have to tell themselves that they’re acting on their own behalf, like Swearengen, but if you look carefully, you know the last person you see in last season’s final episode is this crippled girl, Jewel (Geri Jewell), dancing with the doctor. Now what good does it do for Swearengen to have her working in his place?

“But he got all of his girls from the orphanage where he himself was raised—all those prostitutes that he seems to abuse, he’s also saving. And the girl with cerebral palsy is from there as well. You save yourself by reaching out to other people.”

White hat, with a little tarnish

As the main tent gets set up for lunch, more and more of the extras, or background talent, wander in for several scenes that will be filmed once the sun goes down, most of them driving in from Hollywood and other points south of Newhall. Even though they won’t be shooting anything for several more hours, they’ve already stopped by wardrobe on their way in, and so the set and the lot is starting to fill up with authentically costumed characters.

Costume designer Catherine Jane Bryant decided early on to resist dressing the cast in Western garb. “This was South Dakota, not Arizona, and I wanted to stay away from cowboy costuming,” Bryant says. “So we see Derbys and short-brim fedoras, East Coast and urban fashion on the men and women, some immigrant clothing. People came from all over to take advantage of the boomtowns that were springing up at the time, and it gave me a great opportunity to be more adventurous in my choices.”

Which isn’t to say there aren’t a few real cowboys to be found dressing the set, like world champion steer roper Allen Keller, who delights in telling stories of his adventures on several Sam Peckinpah films and in Michael Cimino’s infamous Heaven’s Gate. Another is three-time world champion bronc rider Monty “Hawkeye” Henson, who introduces himself twitching, stuttering and declaring, “I ain’t never been b-b-bucked.”

Outside the lunch tent, some of the talent is singing and strumming, and while the music is not without charm, Sons of the Pioneers these guys ain’t.

Horses pass, some of them pulling wagons, and as the evening draws on, the set of Deadwood comes to life.

While the crew is setting up lights and camera tracks for a night scene between Swearengen and the new mayor, E.B. Farnum (William Sanderson), an interior shot with Seth Bullock (Timothy Olyphant) is finishing up at the far end of the street inside the Bullock home.

Bullock is Milch’s take on the traditional white hat of Western lore, and, as might be expected, he’s endowed Bullock with a much greater degree of complexity than is usually afforded the historic heroic figure.

“Bullock is the hat because he looks like the hat, for one thing, but it’s important to remember that in actual fact, Bullock was just as crazy and vicious as the ones he’ll eventually go up against,” Milch says. “It’s important to remember that he’d been beaten so continuously when he was a kid by his dad—who was a sergeant major in the English army and had been thrown out of the service and had moved to Canada.

“The result of all that abuse is that Bullock was afflicted with the Stockholm Syndrome, where you identify with your captor and imitate his behavior. You’ll see in the first episode of the second season, he nearly beats Swearengen to death, but that’s how you pick your peace officer—you get a personality capable of just as much violence as the criminal entrepreneur but in whom it’s accidentally associated with an idea of order.

“I was just writing a speech for Swearengen where he says to Bullock, ‘Some people you look at their mug, and you see a truth about them. First time you looked at me, what did you know about me?’

“Bullock says, ‘You’re a murderer.’

“Swearengen says, ‘That’s what’s on my mug. Now you look at that girl over there, you know she’s f—– for money. You see Tom Nuttal (Leon Rippy), when his bicycle arrived, and you can see he had a happy childhood.

“‘The thing with you Bullock is, you’re so f—–’ confused, people look at you and they don’t know what the f— you are. Are you a

c— struck near-maniac, or a stalwart individual moved by principle? People can’t tell because you’re so nuts you don’t know! A strong personality, vague of motive—you’re the perfect candidate for public office.’”

“It’s the sinners that aren’t aware, who don’t believe they’re capable of sin who are the real dangerous ones,” Olyphant says about his character. “The ones you want, the ones you can live with, are the ones who acknowledge they’re capable of sin.

“There’s a sense that Bullock attaches himself to the idea of law and order because he’s afraid of what he’s capable of. What I most like about this character is the possibility that if the show continues over time, Bullock will find his way to becoming who he was historically, and at the same time, work his way through his confusion.”

Milch adds, “Speaking of law and law enforcement, it’s a historical fact that Wyatt Earp came to Deadwood and that Bullock threw Wyatt Earp out of town the next year. Earp came in to try to organize for George Hearst and Bullock beat the sh– out of him. We’ll be seeing Earp in the next season.” (A Deadwood rep cautions viewers that Milch could change his mind, and Wyatt Earp may not join the series until the third season.)

In fact, Earp was in Deadwood through the winter of 1876 and the spring and early summer of ’77. How and why he left Deadwood seems a matter of some conjecture, but the idea that Earp may have formed an association with Hearst and Wells Fargo at that time is a fascinating one, since Wells Fargo played a role in the Earp saga during Earp’s Tombstone years.

As for millionaire George Hearst, father of William Randolph Hearst, it’s certainly true that Hearst and his partners will be a major plot element in the seasons to come.

“Hearst was like Rupert Murdoch,” Milch says. “When you look at guys like these, you don’t look for something extra or something special, you look for something missing in their personalities. They have no sense of scale, no ability to be satisfied—they’re not like the Al Swearengens of the world, who were really mostly interested in what satisfied them: how many times they could get laid. The ore in Deadwood was very low grade, and the only way to make it economical was to own all of it, so Hearst said, well then buy all of it. And that’s what he did.”

Truths of storytelling

It’s nighttime finally and Deadwood’s main thoroughfare is set with flaming torches and plenty of background talent, all looking busy and completely at home, as Swearengen and Farnum meet up for a brief moment of dialogue.

Cinematographer James Glennon is lining up his camera and trying to get a fix on the exact amount of smoke the shot will require. He’s the son of legendary cameraman Bert Glennon, who shot many of Hollywood’s greatest pictures (including John Ford’s Stagecoach, Rio Grande and Wagonmaster), and he’s also responsible for About Schmidt and HBO’s creepy Carnivàle. Glennon tells me that he has, in his truck, the camera his father used in Cecil B. DeMille’s original Ten Commandments from 1923.

“I don’t want to go out on a limb or jinx the production, but I think HBO wants to keep us around, and I’m glad because I get to tell a story with the kind of wide canvas a story like this requires,” Milch says. “As for mixing historical fact with metaphor, let me say that the truths of storytelling are not the truths of correspondence to some external and verifiable reality—that’s reportage.

“For me, the truths of storytelling have to do with an internal emotional coherence, and if I feel the materials are coherent emotionally then I feel it’s true for the purpose of the story. At the same time, I don’t want to fly in the face of the externally verifiable truths because I feel it was that truth that was the springboard for my imagination.

“This production is a single organism in the same way the camp was a single organism in the same way that history itself is a single organism. It’s finding the balance that counts.”

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Paul A. Hutton –