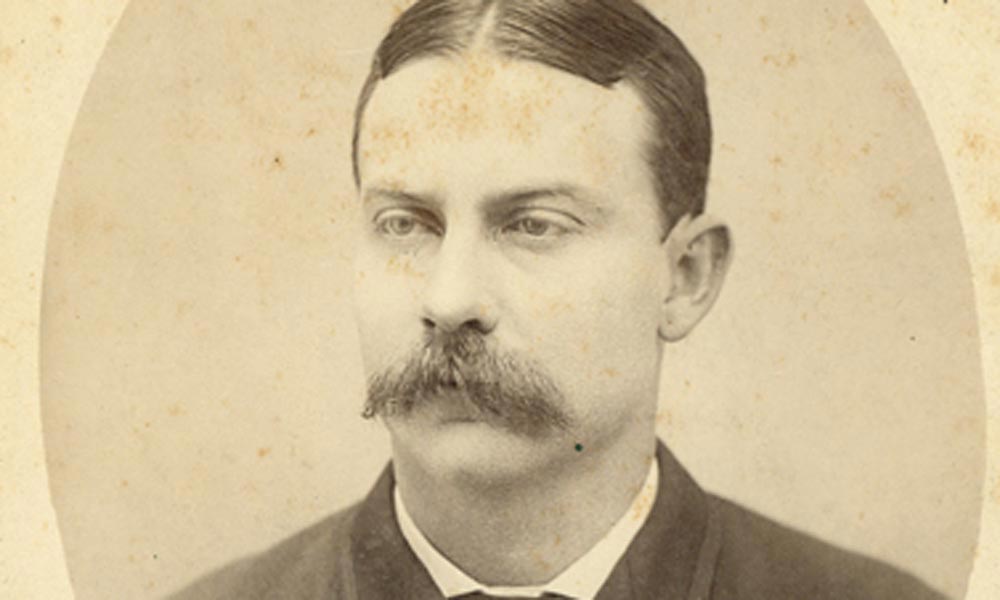

With her black bag in hand, Dr. Sofie Herzog broke all barriers as a female frontier physician in Texas.

Courtesy Chris Enss

The gunshot victim occupying a room in Dr. Sofie Herzog’s office winced in pain while struggling to remain still. His discomfort was not entirely due to the bullet lodged in his abdomen but in the uncomfortable position the Brazoria, Texas, physician had him placed. The lower half of the man’s body had been raised with his ankles fastened to a horizontal pole. The upper portion of his body was flat against the mattress. Dr. Herzog’s procedure for removing bullets and buckshot were unconventional but had proven to be successful. It had been her personal experience that probing the wound in search of the bullet with a surgical instrument was detrimental to the patient. If, indeed, she had to do any probing at all, she preferred to use her fingers, but that was only a last resort. After tending to more than a dozen gunshot wounds, the doctor had learned the most effective way to deal with such an injury was to let gravity do the work. When the victim’s body was elevated, the bullet often found its way to the surface for easy extraction.

Dr. Herzog’s reputation for the treatment of gunshot sufferers spread rapidly throughout the region in the 1890s. Her talents were in constant demand. When she’d removed more than 20 bullets from outlaws and lawmen alike, she had a necklace made from the slugs with gold links to separate each projectile.

Sofie Deligath was born on February 4, 1846, in Austria-Hungary. The precocious young woman eventually followed her father’s example and pursued a career as a physician. At the age of 14, before she fully realized it was possible for a woman to become a doctor, she married a prominent Viennese physician named August Herzog. Between 1861 and 1880, Sofie gave birth to 15 children, among them three sets of twins. She lost eight of her children to various illnesses while they were still infants.

“An eccentric individual with an independent spirit, Dr. Herzog pushed the boundaries of proper societal behavior for women….” —Inscription on the Texas Historical Commission Marker for Dr. Sofie Herzog, 2018

August accepted a position with the United States Navy hospital in 1866 and moved his family to New York City. While caring for her home, children and husband, Sofie decided to study medicine. Training for women in the profession in the states was limited to midwifery. The aspiring doctor not only took advantage of those limited courses but also traveled to Vienna to attend school. The stigma of women learning medicine was less controversial in Austria.

Armed with a certification in midwifery in 1871, Sofie returned to the U.S. and began practicing medicine. She continued her education in the states, receiving a degree in 1894 from the Eclectic Medical College. She worked as both a midwife and physician on the East Coast until her children were grown and her husband passed away in 1895.

Dr. Herzog traveled west shortly after her husband’s passing. The couple’s youngest daughter was living in Brazoria, Texas. Sofie decided to make her home and open a practice there after spending time with her daughter, son-in-law and her grandchildren. She adapted quickly to her new surroundings, which were wild and rustic compared to where she had lived and worked in New Jersey. Brazoria was an agricultural town. Sugar and cotton mills provided the bulk of the employment and income for the region. Federal soldiers, Northerners, foreign immigrants, Confederate soldiers from Texas and the South, ambitious businessmen and desperados filtered in and out of the location, and many of the disputes that erupted because of combative, unruly individuals were settled with six-shooters.

Patients without gunshot wounds who couldn’t make it into town to see a doctor depended on physicians traveling to them. Dr. Herzog made her way to homesteads and farms across the rugged trails on horseback. Those who objected to a woman being a doctor quickly set their biases aside when they were stricken with pneumonia or needed a broken bone mended. Adorned in a split-skirt and black coat, with a man’s top hat covering her short hair, the 50-year-old physician visited the sick and hurting in and around Brazoria.

Dr. Herzog was not only the sole female physician in town, but she also served as the pharmacist. She always had ingredients at the ready to mix laxatives, treat malaria, check diarrhea or help with upset stomachs, migraines and hemorrhoids. The residents of Brazoria trusted the lady medic and fondly referred to her as Dr. Sofie. She made history in 1897 when she became the first woman to join the South Texas Medical Association. Six years later, she made history again when she became the first woman to be elected vice president of the organization.

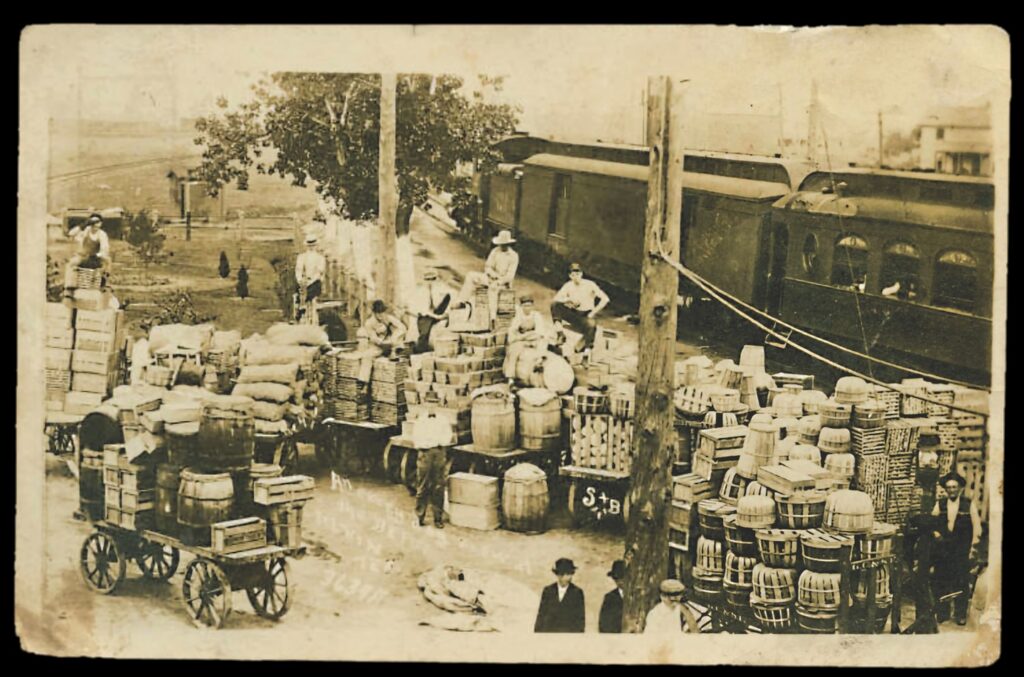

In the spring of 1904, the St. Louis, Brownsville and Mexico Railway began work on expanding the line that ran from Brownsville, Texas, to Houston, Texas. Hundreds of railroad employees filtered into the area to survey land and lay track for trains bound for Brazoria and surrounding communities. Dr. Herzog was frequently summoned to tend to the railroad workers along the line who were either sick or injured. Railroad executives soon recognized a designated physician needed to be added to the payroll, and they offered the job to Herzog. She accepted the position as “railroad surgeon,” but, before she officially began work, she received a telegram from the board of directors of the line. Hiring a woman doctor seemed inappropriate to the railroad executives. They politely offered Herzog a way out, letting her know how understanding they would be if she reconsidered taking the job because it wasn’t suitable for a lady. Dr. Herzog responded with a telegram that assured the gentlemen she was up to the task and that her gender wasn’t a factor. She let them know she’d only step down if they fired her for not doing the work. No more discussion was had on the subject in the 20 years she was employed with the railroad.

An article about the headstrong and accomplished doctor and her work with the railroad appeared in the January 4, 1910, edition of the El Paso Herald. “No railroad surgeon in the country is prouder of the title than is Dr. Sophie [sic] Herzog of Brazoria, Texas, who is the only woman in the United States to enjoy that distinction,” the report read. “Dr. Herzog has been a practicing physician in this country for nearly 20 years, the formative years of her American career having been spent in New York state. When she moved to Texas, her fame as a surgeon soon spread, and her reputation reached the ears of men backing the construction of the St. Louis, Brownsville & Mexican railroad, and she was employed as the official railroad physician. She has been retained in that capacity ever since.

“No matter what time of day or night she is needed, Dr. Herzog leaves her home for the scene of railroad accidents or other trouble. Freight cars, ‘wildcat’ engines, and handcars alike have been her mode of transportation when haste was necessary, for she does not balk at any conveyance when it gets her to her destination in a hurry.”

Although Herzog was employed by the railroad, she continued to maintain her own practice. Not only did she treat those suffering with everything from deep cuts to pneumonia, she was also intent on finding cures for more serious ailments such as smallpox. Her office was in her daughter and son-in-law’s home until her son-in-law learned Dr. Herzog was treating people with highly contagious diseases there. He did not want to run the risk of his wife, children or himself getting infected, so he asked Sofie to leave. The doctor then opened a clinic near the railroad. The building was large enough for her practice and included an examination room, waiting room, a pharmacy and her living quarters.

Dr. Herzog’s office was unique because, in addition to the usual elements found in a medical practice, the pharmacy area looked more like a mercantile. The doctor had several items on display for sale including postcards, lace doilies, walking canes and tonics she made herself. Among the ordinary merchandise was a collection of oddities that sparked Sofie’s fascination such as taxidermy animals, snake skins, antlers and bear rugs. She also had an enormous collection of books and invited citizens of Brazoria to borrow any title they wanted at any time.

Dr. Herzog’s interests were varied. She briefly ventured into real estate, opening the Jefferson Hotel on October 9, 1908. Her desire to maintain historic burial places led to her supplying the funds to build Brazoria’s first Episcopal church and cemetery.

A widely circulated newspaper article about Dr. Herzog’s career in January 1911 noted that in the last 10 years the well-known physician had had many offers of marriage. When the reporter asked for a picture to accompany the published article and told Sofie he was going to mention the proposals she had received, she replied, “If you can find a husband for me, I can support one. He need not do anything except call me ‘honey’ and ‘sugar plum.’”

Dr. Herzog accepted Col. Marion Huntington’s invitation to be his wife in the spring of 1913. Before the pair was married on August 23 of that same year, Sofie had a prenuptial agreement drafted and signed by her future husband. Their marriage certificate is proof Sofie wanted to maintain her independence after the couple was wed. She insisted the document read Mr. Marion Huntington and Dr. Sofie Herzog. Sofie was 67 when she married for the second time.

Shortly after Sofie and Marion were wed, she traded her horse and buggy for an automobile. For the duration of her career, she made the rounds to see her patients in a Ford Runabout.

Dr. Sofie Herzog Huntington died of a stroke at a hospital in Houston on July 21, 1925, at the age of 79. The beloved physician was laid to rest wearing the necklace she had made from bullets she had extracted from gunfighters in Brazoria.

Gunshot Wounds

By Sofie Herzog, M.D., Brazoria, Texas

The term “gunshot wound” is applied generally to all injuries inflicted by missilos [sic], whatever their character, whose force is derived from the explosive power of gunpowder, but as we have had most to do with those whose caliber range from 22 to 45, I will only speak of removing and repairing this kind of injuries. I will especially describe what I do when I am called to a person who has been shot and the result of the injury.

The country physicians have many shooting calls, as no-goods shoot every chance they have. Accidental shooting is seldom. When I have arrived, I inquire how the shooting was done, position of the person, distance, Winchester, or pistol. I never probe. I desire that the bullet shall come to me, and I’ve never failed to get it. I have lived in Brazoria for 22 months, and, during this time, I have been called in 15 times to remove bullets and twice for shot. I got the bullet out every time and never lost a case.

I first insert my finger in the entrance made by the bullet with forward motion in the direction which the bullet had taken, and I nearly always find it this way, because wherever the bullet goes there is pain. The principal thing is to know the position of the patient when the bullet entered the body. I do not touch the wound, and if I cannot find the bullet with my finger, if possible, I wait. I put the patient on the side corresponding to the entrance of the wound, and in this way, I never fail to get it because the heavy weight of the bullet gravitates to the wound entrance. If the bullet entered the abdomen, I put the patient in a hanging position so that the back is upwards, and the bullet will, by its own weight, come out this way. I had two calls of this kind—one, that of a .22 and in the other a .38 caliber. The first, a boy 14 years old, shot himself while cleaning a pistol. The bullet entered the abdomen half an inch below the umbilicus. I was called one hour later, after another doctor had failed to locate the bullet. There was slight hemorrhage. I closed the wound with absorbing cotton, then put the patient in a hanging position, two inches above the bed. Twenty-four hours later, I removed the cotton with a quick pull, and the bullet fell out with the cotton. The boy was well in one week.

The other case was that of a man twenty-eight years old. He was shot in the abdomen one and a half inches to the left of the umbilicus. I treated him the same way as I did the boy, and, the next day, I removed the bullet without trouble.

To see if my treatments were right, I probed the third call of this kind which I had with the “Feuhrer” probe. I could feel the bullet, but, when I went to remove it, the bullet slipped out of the way, and I failed to get it. The man died. I made an incision where the bullet had gone to see where it stopped, and I found that it had been pushed out of the way by the probe.

The repair of the gunshot wound is often disturbed by foreign matter, such as [a] portion of clothing, gun wadding, etc. Severe hemorrhage seldom occurs, especially, as arteries and veins are not injured because of their nonresistance and elasticity; they are frequently pushed aside. There is one thing I want to say—if ever you have to deal with shot wounds, abdominal, never let the bowels come out, as your patient may be lost. I have had severe cases, but all were out on the twelfth day. If you come to Brazoria, I will show you my seventeen men who are well and ready to shoot as well as to be shot at any time.

My treatment is, after I know the location of the bullet, to give hypodermatic [sic] injections of cocaine. I make the incision according to the hole in the skin. Never make a long incision in the face or neck – always make it according to the wrinkles and folds, because the wound heals quicker, it prevents scars, while it will not be so disagreeable and looks better. After the removal of the bullet, I make one or two stitches, fill the cavity with acetanilide, cover with absorbing cotton, and bandage the wound up. I do the same with the wound of entrance; after three days, I remove the dressing and close only the entrance; the exit I leave open, but dust with acetanilide.