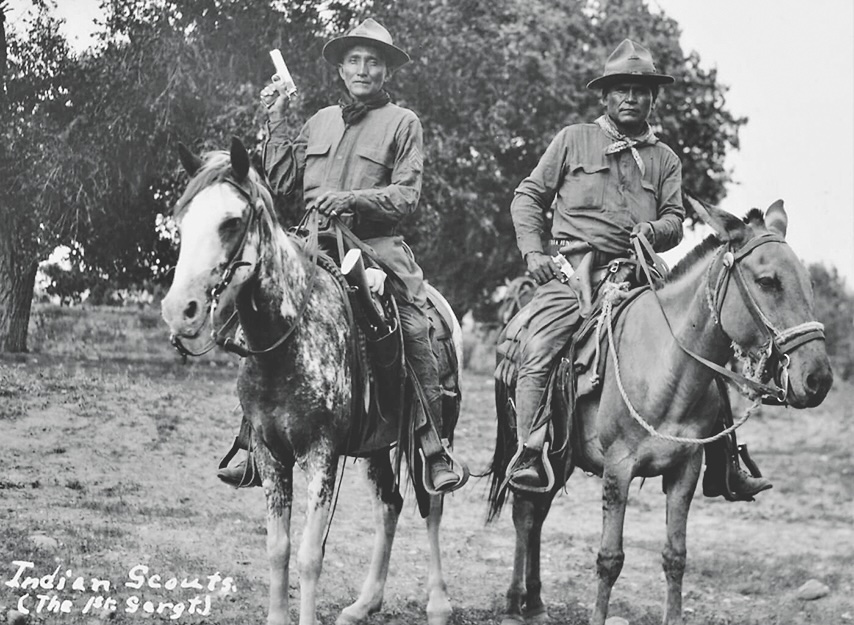

to a treasured past.” Courtesy National Archives, The Armory Life

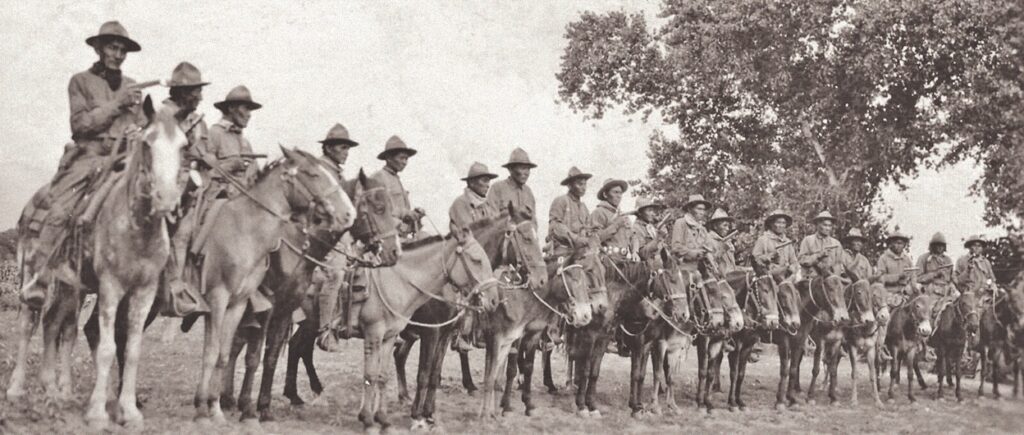

General John “Black Jack” Pershing assigned the Apache scouts from the 10th and 11th cavalry the task of tracking Pancho Villa. (Enjuh! It is good, they acknowledged.) The taste of new adventure and the hunt for the elusive bandit and his soldiers stirred their warrior souls.

The violence and upheaval of the Apache campaigns of the 1880s were long past. Compared to the dozens of scouts and troops who combed the Southwest and Mexico for renegade Apaches refusing to be confined on reservations, 1916 was pretty quiet. These particular Apache scouts were a band of brothers; they were tough and could track, fight and ride as their predecessors once did, but they were also immobilized in a time warp with tedious, uninspiring duty. That changed dramatically on March 9, 1916, when Pancho Villa and his angry revolucionarios had the audacity to wreak havoc on the border community of Columbus, New Mexico.

Sprawled along the border, the small town was a blur of dust devils and no rain. The Mexican Revolution had brought betrayal and bloodshed for six long years to many citizens of both nations. The shock of that brutal assault on U.S. soil would not be tolerated. Villa had badly misjudged the leadership in Washington, and while hoping to jumpstart the purpose of the revolution, which was “Tierra y Libertad” (land and freedom), this unfortunately backfired. The angry “bandit” general finally cut ties with President Woodrow Wilson and all the political chicanery of that administration’s lackadaisical attitude toward Mexico. Fury had overwhelmed Villa when he learned that the U.S. was supplying arms to his bitter rival, Venustiano Carranza. Villa despised Carranza because by Villa’s rough standards the man was a coward and a pompous rico who had achieved power without fighting the evil of General Huerta. Thus, the treachery of the United States stung, and Villa did what he knew best—he rode out of nowhere and attacked, killing and maiming citizens of the U.S. and leaving his own war dead strewn across the landscape.

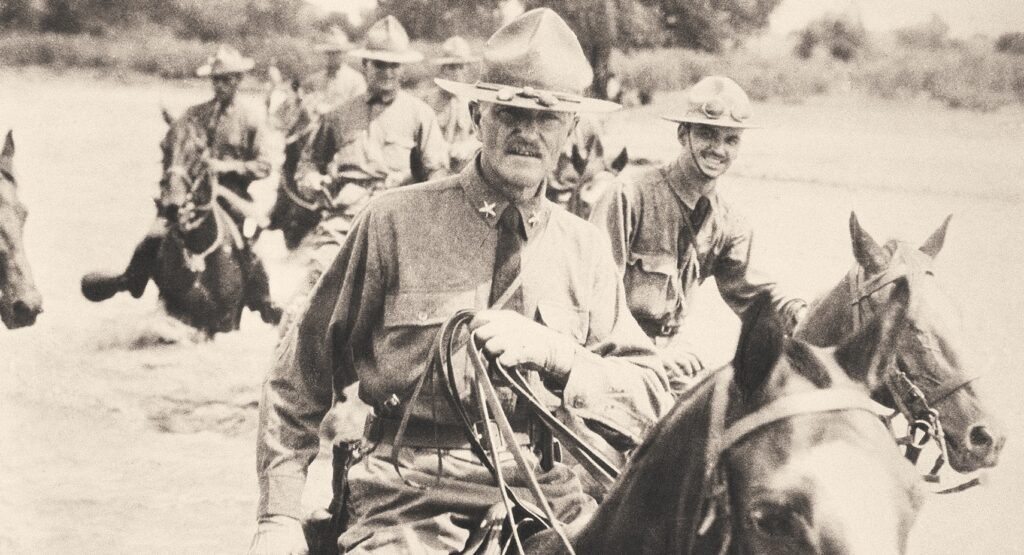

The United States government, usually slow in its reactions, seemed to move like the wind. Within a short time thousands of men were called to duty to capture and punish Villa and his Dorados. Selected to lead this “punitive expedition” (also known as the Mexican Expedition) was Brig. Gen. “Black Jack” Pershing.

Pershing well remembered his frontier experience and service in New Mexico during the Indian wars. He was a strong disciplinarian and had a gift for organization. Wanting to complete the assignment quickly and efficiently, Pershing submitted a special request for Apache scouts because he was familiar with their ability and expertise in tracking techniques. Now, if Pershing could just get Washington off his back. Unfortunately, President Woodrow Wilson was always trying to second-guess his military commanders.

Little did the scouts realize that the few years they had remaining would pale in comparison to the exciting months chasing Villa, scouting for Gen. Black Jack Pershing and serving their nation.

Old Traditions Die Hard

Several of the older scouts had served or had relatives who served during the Geronimo campaigns. Only 24 remained in 1916, however Pershing increased their ranks to 35 during the Punitive Expedition. They would serve their last major assignment yet again in Mexico. Despite 30 years of relative peace along the border, Apache scouts were a little nervous about riding into the land of their traditional enemy, the Mexicans. Their view of the world did not distinguish between friendly Mexicans and the Carranzistas or Villistas. To their minds, “shoot ’em all” seemed to be the order of the day. Caution was much more a part of the march forward than they anticipated.

Ace Daklugie, nephew of Geronimo, told historian Eve Ball when describing scout activity that an Apache never wanted to be surprised. No surprise equals survival!

Successful commanders, including Capts. John G. Bourke, Emmet Crawford and Lts. Britton Davis, Charles B. Gatewood, James Shannon and H. B. Wharfield, realized the greater leeway they allowed the Apache scouts with regard to their culture and beliefs, the more responsive their attitudes would be toward military life.

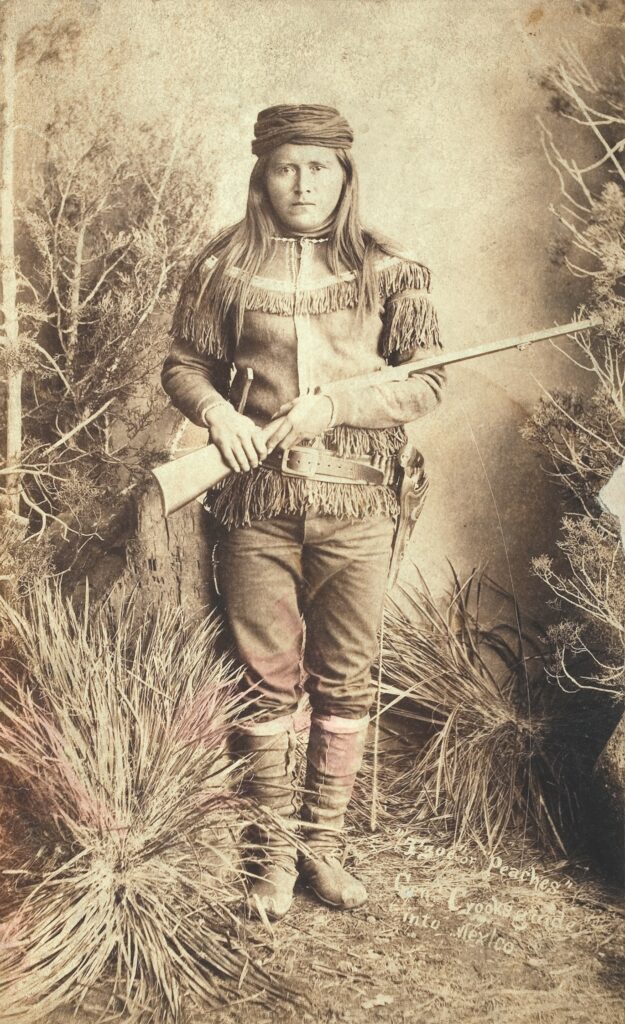

U.S. Army Capt. John G. Bourke described the Apache scouts on the campaign in pursuit of Chiricahua Apaches in 1883 as following the ways of the natural environment. The scout knew every nook and cranny, every trail or mark along the way that told a story of people or animals passing by. A scout’s value was in their natural skills they were taught from childhood.

More than 30 years later, Capt. James Shannon, commanding officer of scouts, wrote:

“In order to get results, he must be allowed to play that game in his own way… This extreme caution…is one of the qualities that makes him a perfect scout. It would be almost impossible to surprise an outfit that had a detachment of Apache scouts in its front.”

Although raised in the East, Lieutenant Shannon had developed a true appreciation for his Apache scouts. He praised them for their keeping an orderly camp, care of their horses and especially their traditional Apache religious rites. He found that they used the sweat lodge almost daily and each man carried several sacred objects of power in the pockets of their uniforms such as hoddentin, the sacred pollen they all valued and used for daily prayers. These were the men following the trail of Villa and his “gang of cutthroats” as the American press now described them.

Battles at Rancho Ojos Azules and Las Varas Pass

Though there were many skirmishes and incidents, two major encounters during which the Apache scouts rode point and relished the battle experience as well as the scouting phase of their duties, occurred in May and June of 1916.

Rancho Ojos Azules

Historian Friedrich Katz called the action at Rancho Ojos Azules the “greatest victory that the Punitive Expedition would achieve!” It also improved morale among the troops. The Apache scouts enjoyed every minute of this encounter. It allowed them to prove they could fight as well as track.

On May 5 after a forced march of 35 miles, a group of scouts and members of the 11th Cavalry came to El Rancho Ojos Azules. (Blue Springs). Many Villistas were known to be in the area. It could be a great opportunity to actually engage the enemy that had attacked the United States and possibly corner Villa himself. Julio Acosta led some 150 or more seasoned soldiers loyal to Villa. Maj. Robert L. Howze hastily assembled six troops of the 11th Cavalry, a machine gun troop, a pack train loaded with four days’ rations, and the Apache scouts who fanned out as an advance guard for the main column. A handful of American officers and about 140 enlisted men fought against the Villistas. Incredibly, not one American was wounded in battle, but over 50 of the Villistas were reported as killed in action with at least that many captured. Major Howze, eager to field a victory, had continued his forced night march in an effort to achieve total surprise the next morning. Exactly a month earlier he had been forced to give up a pursuit of Villa himself, due to a lack of Apache scouts to follow the trail. His Apache scouts had been accused of committing “atrocities,” thus he had to temporarily suspend their operations. This put the men at a distinct disadvantage without scouts to follow the clever and evasive Dorados. It was very frustrating for all involved.

This time Howze sensed that the trap was closing with the aid of his Apaches and the two civilian guides. At sunrise the combined forces deployed and the Ojos Azules charge began.

According to some reports, Ojos Azules is remembered as the last American cavalry campaign fought in the frontier way. It was clean and near perfect as dozens of Villistas were caught in the cross fire, and this cavalry charge was typical of the americanos’ classic fighting style. Major Howze, with Troop A, was to act as a mounted advance guard for the 11th Cavalry troops. The original plan for the scouts was to find the Villistas and prevent them from escaping. However, the Apaches, unable to resist once they located the enemy, dismounted in their traditional style and fought until the remainder of Howze’s troops arrived. It was reported that they fought well side by side with regular cavalry troops. A charge with pistols through the ranch made in columns of four ended with the enemies fleeing for their lives. Other troops deployed to either side of the ranch house blocked escape by use of the machine gun brigade. Apache scouts eagerly led the way against their traditional Mexican enemies. This was an unusual move in that scouts were supposed to locate the enemy and then get the hell out of the way.

First Lieutenant S. M. Williams, adjutant and quartermaster for the expedition, later wrote in an article for the US Cavalry Journal about his experiences at the Ojos Azules fight describing that this battle lasted for at least 20-25 minutes of furious fighting accompanied by Apache scouts shrieking shrill war hoops. Additionally, they also returned to camp with their booty: saddles, bridles, captured horses and mules, ammo, blankets, rifles and pistols. Afterwards, 1st Sgt. Chicken (Eskehnadestah) is recorded as saying: “Huli! Damn fine fight.” His men agreed.

It was a stunning feat for scouts and troopers because the forced all-night march with horses and mules carrying extra heavy loads was difficult for man and beast, and they were war-weary upon arrival at Ojos Azules. Courage and spontaneity carried the day as scouts and soldiers fought together well, carefully and with lightning speed when necessary.

Las Varas Pass

About a month later on June 2, Lieutenant Shannon and his 20 Apache scouts fought with some of Candelario Cervantes’ men. They had stolen horses from the 5th Cavalry. Stealing horses and mules became a game and a hard-fought one in some cases. Though the Villistas’ trail was over a week old, the scouts tracked the men to Las Varas Pass. Captain Shannon noted that his scouts took a short time to re-locate the trail after a rocky stretch caused them to slow. The Apaches circled out and soon one motioned for the others and then the rest started off again using the same technique. Within the hour they quickly dispersed the ladrones (thieves) as they scattered into the mountains. There were no losses of men, but once again, no Villa.

The Ojos Azules and Las Varas Pass battles did not go unnoticed in Carranza’s Mexico City, even though the casualties had been entirely Villistas. Villistas at Ojos Azules later admitted that fighting against the feared Apaches was an unnerving experience. On June 28, 1916, Mexico’s representative to the United States, Eliseo Arredondo, sent a harsh note to Secretary of State Lansing contending again that Pershing’s officers and Apaches had committed atrocities that would not be forgotten. Pershing responded that these rumors had persisted for some time, but that investigations showed the charges to be unjustified. General Pershing’s findings have satisfied historians ever since then. Unfortunately, it slowed down the progress in finding Villa for several months. Remarkably, the military reports of their commanders indicate the officers all believed that with better usage of the scouts, Villa himself would have been apprehended! That was the purpose, after all, of the Punitive Expedition. Mexico City was as inept as Washington was when it came to understanding field conditions—lucky for Villa but not for Carranza and his autocrats in the capital.

During the seven months of waiting to “placate” Carranza, the Apaches spent a significant amount of their Mexican service tracking down American deserters and general scouting or hunting forays and repairing telegraph wires cut by the enemy. Shannon took his scouts out for hunts just to prevent boredom and returned with a changed attitude when it came to his men’s tracking abilities. They not only found the animals’ tracks, but also relied on their knowledge of wildlife habits to supply camp with fresh meat, whereas the white soldiers assigned to bring in fresh meat failed to do so in the same general area.

Scouts tracking deserters always got their man. After three soldiers disap-peared without a trace, the Apaches located the “invisible trail” because an observant scout found that a fast-moving horse had stumbled in a prairie dog hole and a piece of cactus had been broken off in an unnatural manner on down the trail. The scouts moved silently and quickly using only hand signals. Within 24 hours they had caught up with the deserters. This technique was repeated many times.

Courtesy N.A.R.A.

Villa Has the Last Laugh

Mexico was an untamed, desolate land, especially in the vast wilderness cordillera known as the Sierra Madre. Villa knew the countryside. Pershing’s troops did not. The campesinos loved Villa and his Dorados. They hated the gringo. Mexicans did not want Americanos on their soil. Thus, the only real edge Pershing had were Apache Scouts recruited much as they had been in tracking down renegades during the Apache Wars of the last century. It was a wise decision.

The Punitive Expedition was possibly the final military operation to enter combat in the old frontier style of warfare and emerge as a different force with truck convoys and men on mule or horseback riding side by side into a new “modern” era. That was unless they had to follow dim trails of outlaws and Villistas into the rugged Sierra Madre. There were few roads. Mostly, there were dangerous paths following the terrain of canyon and gorge. Pershing knew it was important to use every resource and method to be successful in such terrain. These were not just trails into town plazas. They could be traps for his men. Villa, Fierro and others might be hiding in the nearby hills. In some cases that was true because the Apache Scouts located caves along with stored supplies, ammunition and arms. Nevertheless, despite using all resources available, Pershing was continually outfoxed by the clever revolutionaries. Some bloody incidents gained a few prisoners as well as the anger of the Mexican residents of tiny pueblos, and this carried over into the large city of Chihuahua that was Pershing’s headquarters. And, of course, the city was also Villa’s old stomping grounds. It was embarrassing to admit, but after more than 11 months in field and town, no había ni un señal (there was not even a sign) of the “Centaur of the North.” There were lots of rumors, and lightning-fast ambushes or raids for supplies and horses, but no Villa. The campesinos composed many corridos (folk songs). They serenaded: Maybe they have guns and cannons, /Maybe they are a lot stronger, /We have only rocks and mountains—/But we know how to last longer …

It must have been a bitter pill to accept that if it had not been for the Apache Scouts, they would have never even gotten close to José Doroteo Arango Arámbula aka the bandit general, Pancho Villa

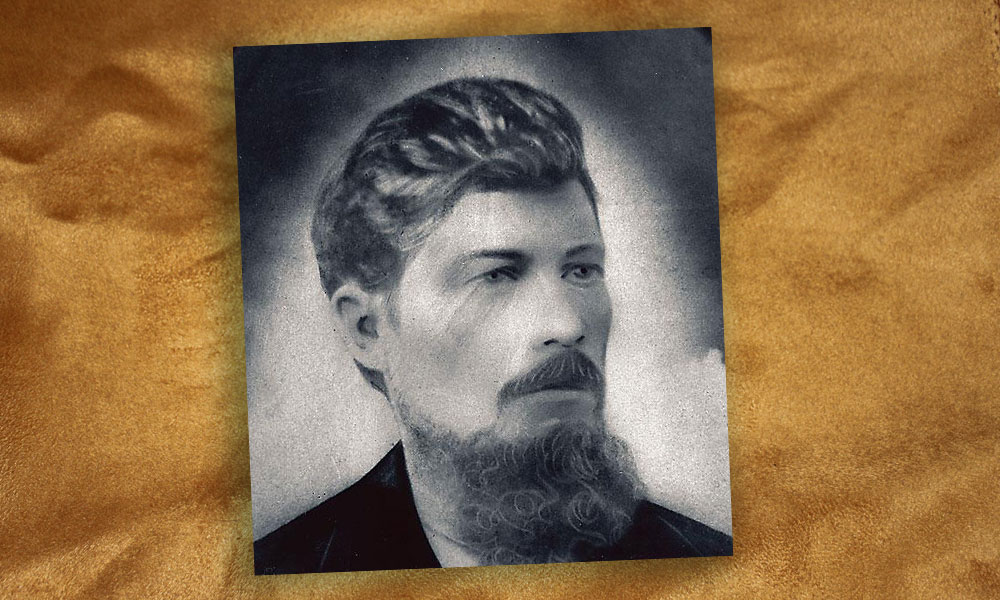

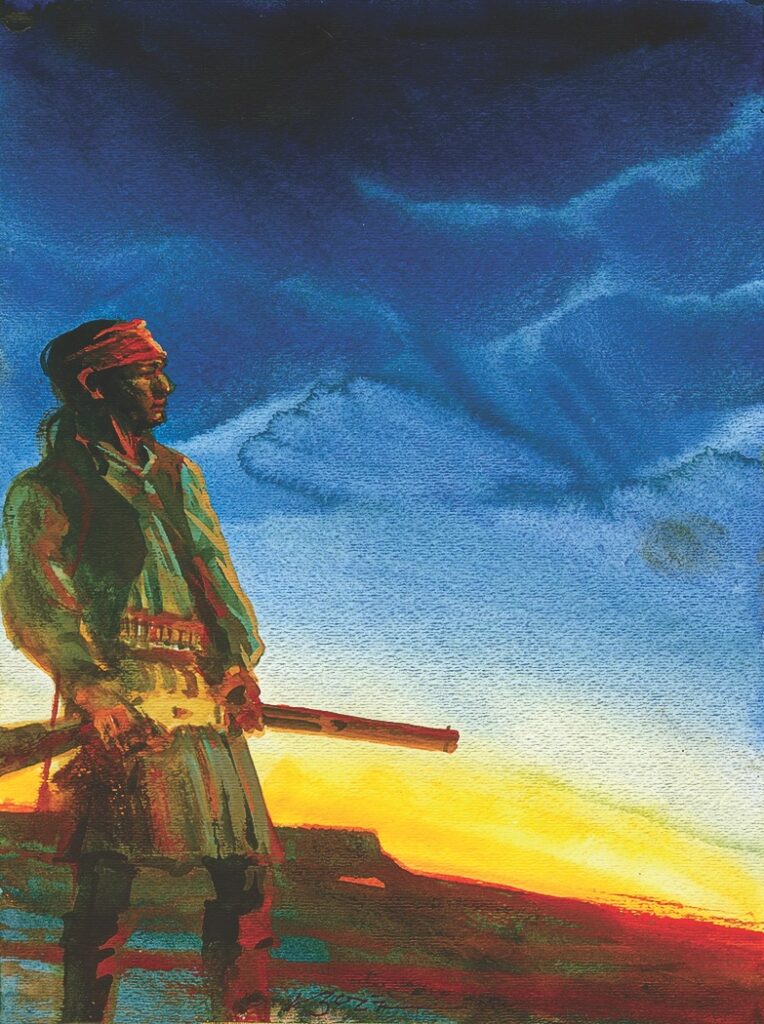

True West Archives

Apache Twilight

After the Punitive Expedition ended in February 1917, the army disbanded about half of the force, leaving 22 Apache scouts for active duty at Fort Huachuca. Their wartime service was not yet over though. Conflict between the United States and Mexican armies continued until 1920, and Apache renegades from the Sierra Madre harassed ranchers until the 1930s. They also formed borderland patrols and saw that cattle did not stray into Mexico. Nevertheless, service under General Pershing and the Punitive Expedition could be considered the “last hurrah” for the Apache scouts.

Illustration by Bob Boze Bell