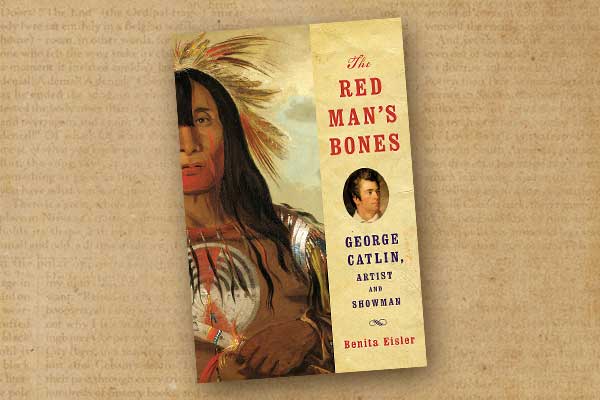

Rising from inauspicious beginnings to national and even international fame, only to fall victim to his own hubris and naivete, artist George Catlin (1796-1872) charted a career of risk-taking extremes that took him from the Northeast and then to Europe for more than three decades as an ex-pat, before dying in his home country.

Rising from inauspicious beginnings to national and even international fame, only to fall victim to his own hubris and naivete, artist George Catlin (1796-1872) charted a career of risk-taking extremes that took him from the Northeast and then to Europe for more than three decades as an ex-pat, before dying in his home country.

Considered the “first artist of the West,” only in the sense that he was the first to live among the Indians he painted, he achieved his most enduring fame as a painter of early 19th-century Indian tribes on the Upper Missouri and the Great Plains. His depictions and writings on the O-kee-pa—the Mandan torture-ritual rite of passage, in which young braves were skewered with splints through their flesh and strung up, bodily, high above the floor of a medicine lodge—was his most provocative and talked-about work.

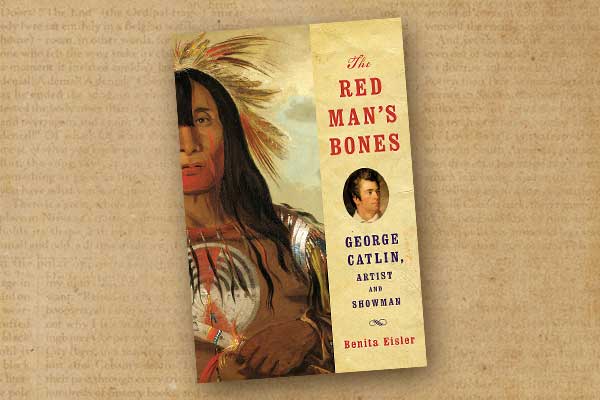

Benita Eisler’s new biography, The Red Man’s Bones: George Catlin, Artist and Showman reveals a Catlin many might never have suspected existed: a fame-driven, footloose, anchor-less soul who was always ahead of his time—even when it came to his own demise.

At the outset, Eisler uses the term “genocide” to describe the U.S. treatment of Indian nations. She thereafter refrains from direct authorial condemnations, opting to let the voices of Catlin’s time bring the charges or the refutations. The book is well titled: this is indeed a book about the nations more than about an individual, though the individual, the painter and showman, holds center stage throughout.

While in pursuit of his dreams, Catlin draws the attention of luminaries such as DeWitt Clinton, Daniel Webster, Jefferson Davis, William Clark, P.T. Barnum, Francis Parkman, George Sand, Victor Hugo, Eugene Delacroix, Asher B. Durand, Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, Alexander von Humboldt, William H. Seward and King Louis-Philippe of France. The interplay between Catlin and these leading lights makes this biography more than a life story. It brings to life a history of the Republic as well, in what might have been its most formative epoch.

Catlin mounted a stage show that prefigured Buffalo Bill’s Wild West by nearly 50 years. For his European adaptation, he brought two grizzlies with him via ship to England. Later he would add Indian performers to the mix.

Eisler writes that the “…grizzlies provided a revealing image of their owner. At this turning point in his life, Catlin’s bears, together with their master, seemed to look both backward and forward. Natives of the Rocky Mountains (where in fact Catlin had never set foot), the grizzlies were displayed as living proof of the artist’s explorations of uncharted wilderness.” The author suggests that Catlin was hoping to convey, indirectly, to European audiences that he had ventured so far into the wilderness as to have encountered grizzly country.

But did he not venture into grizzly wilderness? Many contend that the grizzly’s original range extended through most of the northern Great Plains. Catlin was at Fort Union, on the Upper Missouri, in 1832. A mere nine years earlier, in 1823, Hugh Glass was mauled by a grizzly in what is now Perkins County, South Dakota, roughly 200 miles from Fort Union—and clearly well east of the Rockies.

But such lapses—if this is a lapse—are rare in The Red Man’s Bones. Eisler, an accomplished biographer, has penned life stories of Lord Byron, George Sand and Frédéric Chopin and a dual biography on Georgia O’Keeffe and Alfred Stieglitz. While she might be something of an outsider when it comes to writing Old West material, she brings a refreshing breadth of perspective to the genre. This is a rich and lively narrative of a complex, daring, uniquely talented American.

—Jesse Mullins