How the Osage murders in Oklahoma in the 1920s led to the rise of the FBI

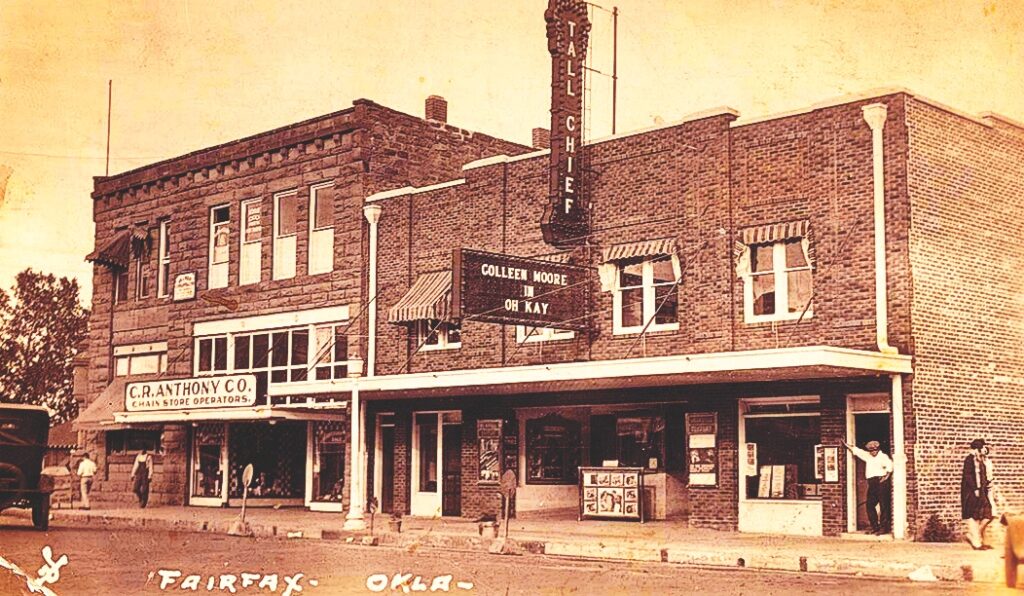

At three in the morning an explosion rocked the small Oklahoma town of Fairfax in Osage County. Five gallons of nitroglycerin had been used to blow up the Smith home, killing Osage tribal member Rita Smith and her White servant, Nettie Brookshire. Smith’s husband, Bill, died four days later.

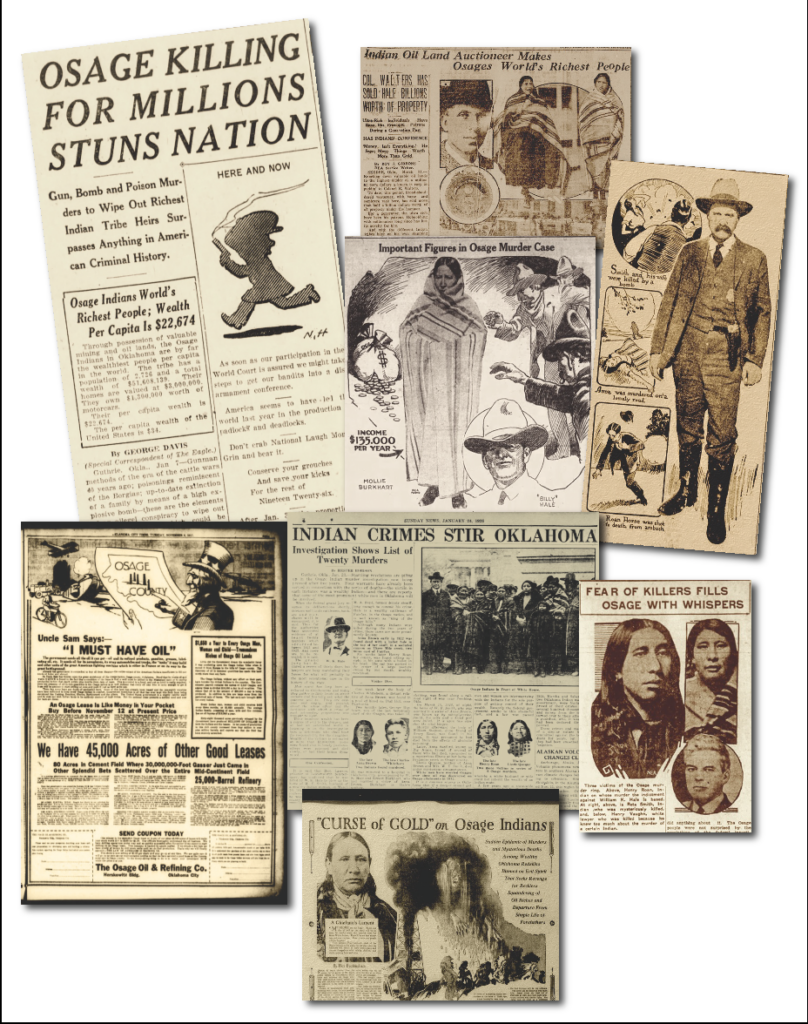

It was March 10, 1923. By then some 27 Osage tribal members had died in the Osage Hills under mysterious circumstances over a two-year period. A number of newspapers were already calling what was going on in Osage County a Reign of Terror.

The Osage Nation was limited in their investigations by White Osage County authorities who had taken a nonchalant attitude on the deaths. Most county towns and the county sheriff’s department were controlled by non-Osage people, although the tribe had settled there by buying the Osage Hills some 50 years earlier to be their reservation.

The Osage are one of the very few Native tribes who were able to select and purchase their own reservation without being forced onto lands they did not want. They even demanded and received their tribal allotments from the federal government in the form of cash payments rather than through supplies that were often late and short, a point of friction between American Indians and the federal government.

From Ohio to Oklahoma

The Osage people began their identity in the Ohio River Valley around Kentucky trying to hold back the Iroquois. But the Iroquois were able to push them west to and beyond the Mississippi River. Yet, by the early 1800s, they were the main military power between the Missouri and Red rivers and were just beginning to come out onto the Great Plains. Their language was related to that of the Sioux people to their north.

The Osage had a reputation for being fierce and powerful warriors. During the relocation of the Cherokee into Oklahoma in the early 1830s, they clashed with the Osage in a series of battles, forcing the U.S. to build Fort Gibson to protect the Cherokee. By this time, the Osage were hunting the Kiowa, who had just been expelled from the Black Hills by the Sioux. In 1883, the Osage slaughtered hundreds of Kiowa women and children at an unprotected village at Cutthroat Gap in the Wichita Mountains, leaving their cut-off heads in pots for the Kiowa warriors to find.

Treaties with the U.S. gradually forced the Osage onto a reservation in Kansas while they were employed as scouts for the U.S. Army against hostile plains tribes such as the Cheyenne. By the end of the Civil War, Kansas settlers wanted the lands of the Osage reservation. The Johnson administration placed pressure on the tribe to move to Indian Territory, modern-day Oklahoma, offering to buy their lands at 19 cents an acre. Tribal elders stalled until Ulysses S. Grant became president then sold their reservation lands to the new administration at $1.25 an acre.

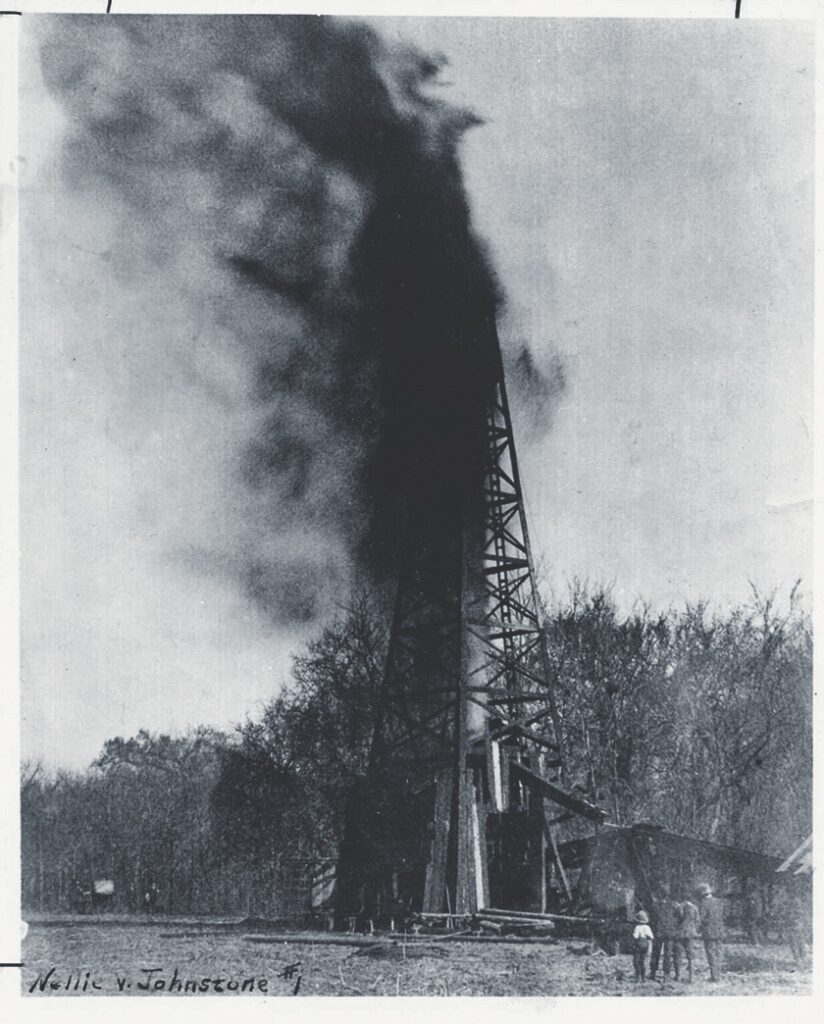

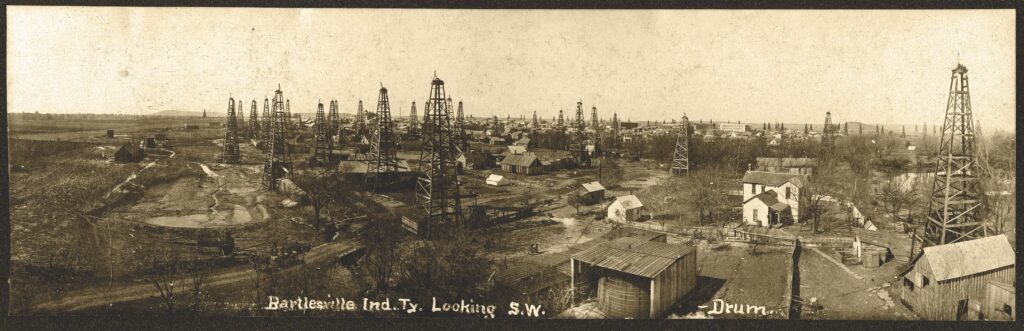

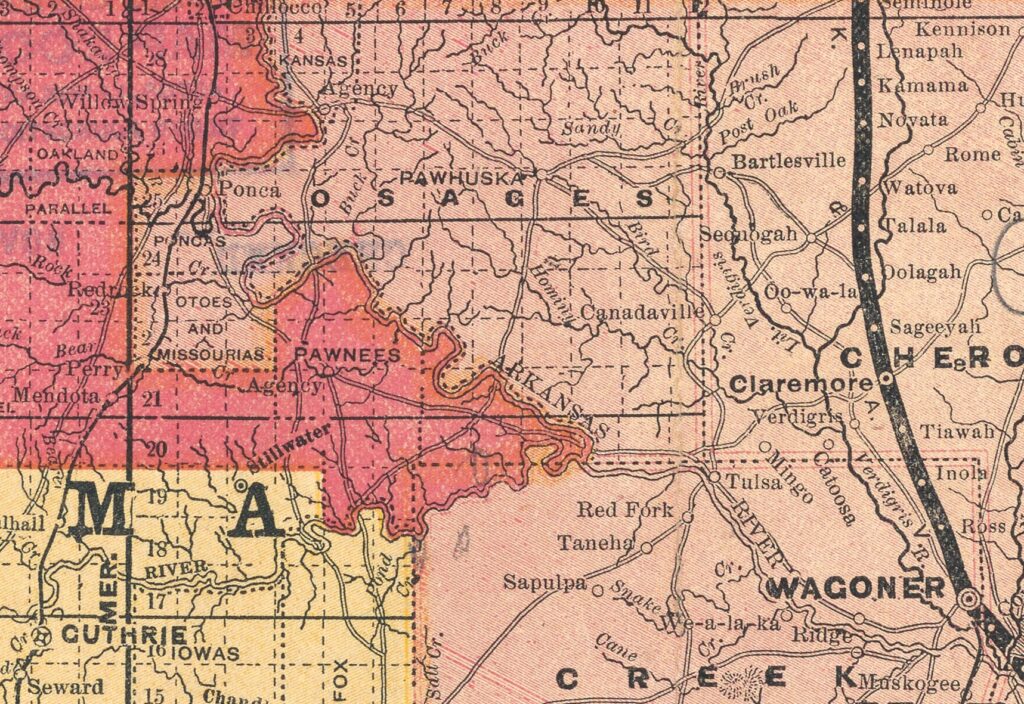

With this money, the Osage managed to purchase from the Cherokee nearly 1.5 million acres, or most of the Osage Hills, with mineral rights and a greater degree of sovereignty than most tribes enjoyed. The tribe then auctioned off grazing leases for Kansas and Texan cattle ranchers, which made them one of the wealthiest tribes in the United States even before the Burbank Oil Field was discovered in 1897. The Osage demanded and received 10 percent of all revenues derived from oil found within the county, which was also their reservation.

Murder Capital of America

The explosion at the Smith family’s home was the last straw for the Osage Nation. U.S. Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover’s uncle was an agent for the Osage tribe and was frantic to find the killers. The murders were also beginning to capture national headlines. The Bureau of Investigation was assigned the case under the office of Bureau Chief J. Edgar Hoover. The case would transform this little-known bureau into today’s FBI.

It was not as if all White lawmen were unresponsive to the mysterious deaths. Authorities simply did not see how the 27 killings differed from the sea of violence everyone was falling victim to in the Osage Hills.

So much oil money was being made that it acted as a magnet for the West’s criminal element. Osage banks were robbed on a monthly basis. Shootouts on main street were commonplace. Posses were launched either on horseback or by vehicle into the vast rolling hills. Train and bank robbers in a gang led by Al Spencer had transformed one wooded valley into their Osage base of operations, while Henry Grammar and his bootleggers, wanted for two killings, hid out in a nearby valley.

Oil roughnecks working the oil fields often brawled in Osage saloons, including one roughneck later to become actor Clark Gable and his father, keeping local law officers busy as well.

The Burbank Oil Field was making the Osage tribe and its members wealthy beyond their dreams. Oil barons Frank Phillips, E. W. Marland, Jean Paul Getty and William Skelly sat under Pawhuska’s “Million Dollar Elm,” where public oil and gas lease auctions were held, bidding for the right to drill into the oil-soaked earth. Drilling rights went as high as $1 million plus. Oil values increased even more when Skelly developed a means of maintaining pressure in the Burbank Oil Field.

Although the tribe opened the Osage Hills to White settlement, they had retained the mineral rights to the vast pools of oil below.

Each tribal member received a “headright” or share of the oil money administered by the tribe. If one died, the headright would go to the nearest heir.

At first, the deaths seem to be unconnected.

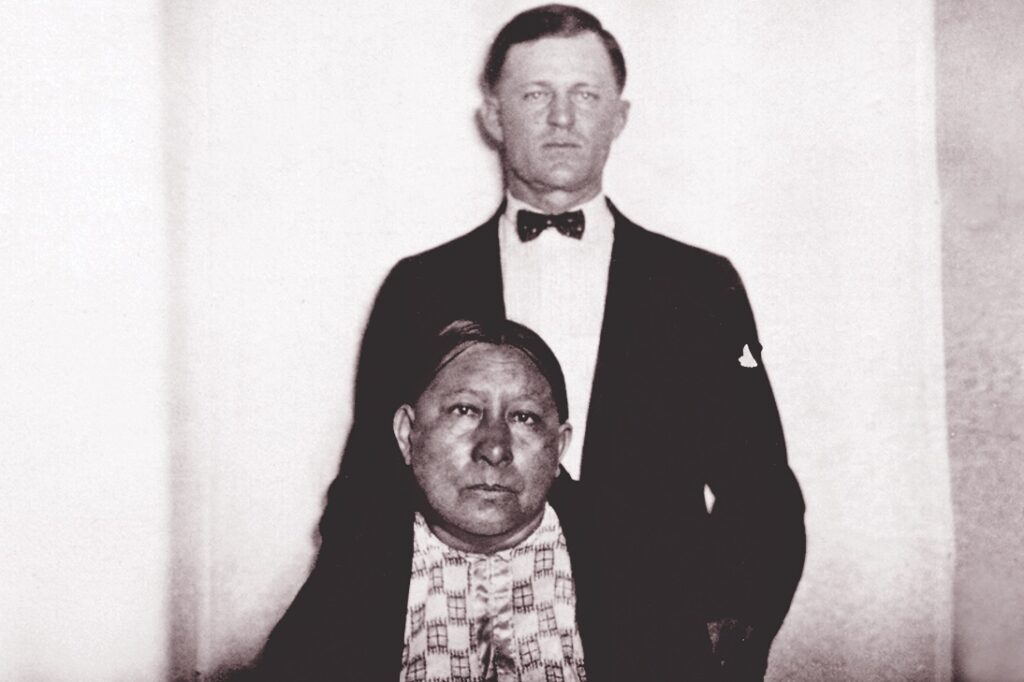

Osage rancher George Bigheart was rushed to an Oklahoma City hospital by his neighbors, William Hale and Hale’s nephew Ernest Burkhart. Along with them was Bigheart’s attorney William Vaughan. Bigheart had asked Vaughan to come along, stating he had evidence that there had been a series of murders taking place and he knew who the killers were. He had documents to back up his claim for Vaughan to look over. Bigheart died from poisoned whiskey shortly after arriving at the hospital.

Vaughan caught a train for Pawhuska that night, but his body was found along the rails the next morning. His skull had been crushed. Bigheart’s will left his ranch to Hale.

Authorities still did not investigate. Hale was an important cattleman in Fairfax.

In late May of 1921, hunters found the decomposed body of 36-year-old Anna Brown in a remote ravine. Local law enforcement officers ruled that she had died of accidental poisoning. The body of Brown’s cousin Charles Whitehorn was discovered the same day just outside of Pawhuska, county seat for Osage County. He had been fatally shot.

Probate awarded Anna Brown’s estate to her mother, Lizzie Kyle. Lizzie soon passed away, though she was in good health. By this time, Lizzie had inherited eight headrights, making her a millionaire. Her family included only herself and three daughters: Brown, Rita Smith, and Mollie Burkhart, wife of Ernest Burkhart. It was her second marriage.

On February 6, 1923, Henry Roan, an Osage, was found dead in his car. The vehicle was sitting out in the open pasture with Roan’s lifeless body inside. A .45 had been used. He had been killed with one shot to the head, execution-style. Soon after, the Smiths’ home was blown up in Fairfax. No one was taking credit for the murders.

But with the Smith explosion, Mollie Burkhart became the sole heir of the family’s headrights.

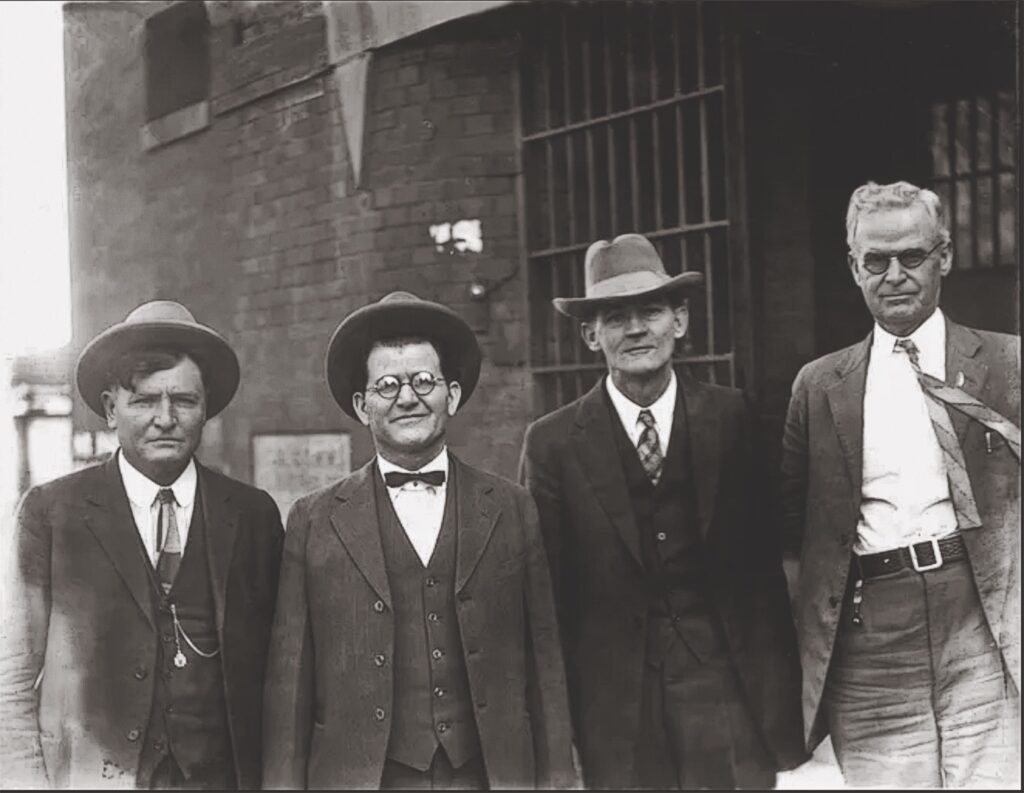

The Osage Hills were now swarming with federal agents posing as cowboys and cattle buyers, while private detectives were also working the area after being hired by oilmen Skelly and Phillips, both of whom were outraged by the murders. When federal investigator Tom White arrived in 1925, local White lawman James Monroe Pyle, a friend to the Osage tribal elders, handed White the evidence that he had collected so far. Warned by Pyle of corruption among local authorities, White brought in former New Mexico sheriff John Burger to work undercover along with agent Frank Smith and John Wren, a Ute tribal member who had previously spied on Mexican revolutionaries.

On the surface the case seemed simple enough. Family members had been murdered so Mollie could be the only heir. Roan had been Mollie’s first husband.

However, no one would come forward. The federal agents were working under the umbrella of the Osage tribal police. They were desperately trying to find a way to make the murders a federal case. The wedge they needed to pursue the case came when they discovered that Henry Roan’s body had been found

on federally owned grazing lands that had been leased out. It was thin, but enough for the murders to be deemed a federal case.

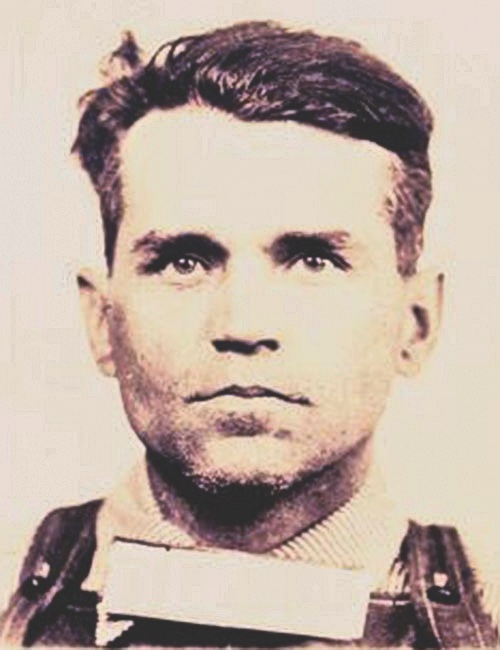

Then a major break came after striking a deal with a prison inmate in the Oklahoma Penitentiary at McAlister. Blackie Thompson had his life sentence commuted in exchange for testimony that William Hale had tried to hire him to blow up the Smith house.

Federal agents now went looking for Al Spencer, but he could not corroborate Thompson’s statement because on September 15, 1923, a posse had killed Spencer for robbing a train a month earlier.

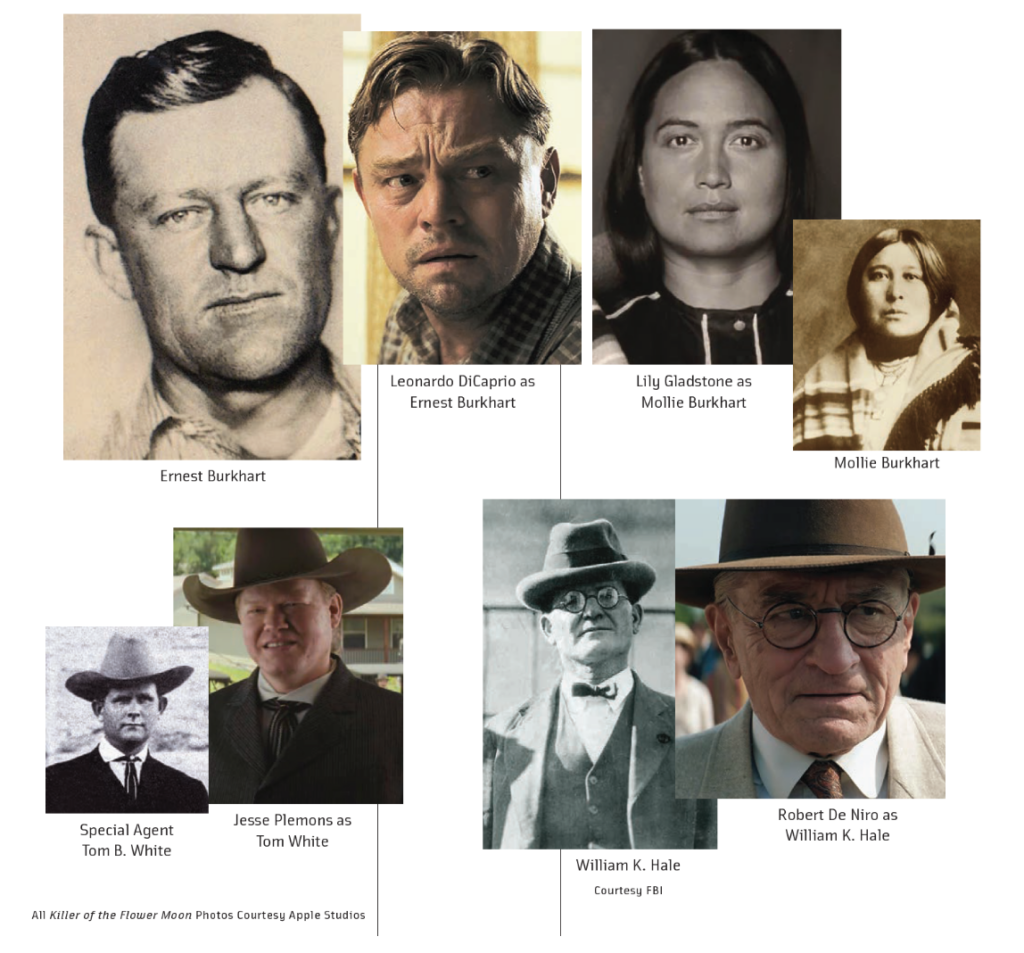

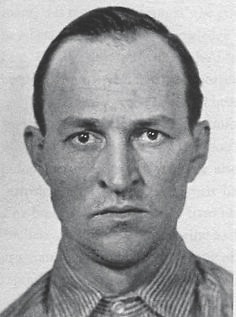

Hale’s criminal allies included Mollie Burkhart’s second husband, Ernest, who under questioning, told the federal agents that William Hale had another associate involved in Henry Roan’s murder: John Ramsey. Two-bit criminal Ramsey quickly implicated Hale as the leader of the murder ring and also named Henry Grammar and Asa “Ace” Kirby as gang members who helped kill the Smiths. Grammar and Kirby were never prosecuted because they died “mysteriously” in the months after the Smith house was blown up.

The first Hale and John Ramsey federal trial in 1926 ended with a mistrial. In the same year, Ernest Burkhart made a deal with the prosecution to implicate Hale and Ramsey in the Roan murder, and he pleaded guilty to the murder of Bill Smith. He was given a life sentence in the Oklahoma State Peniten-tiary in McAlester.

Federal prosecutors retried Hale and Ramsey twice more for the murder of Henry Roan in federal court: in Oklahoma City in 1928, which was overturned by an appeals court, and in Pawhuska in 1929. At the third trial, both men were found guilty and sentenced to life at Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary.

The trials revealed that the murdered Henry Roan had borrowed $1,200 from Hale before his death, and Hale had fraudulently made himself the beneficiary of Roan’s $25,000 life insurance policy.

Also revealed was that Kelsie Morrison, a local criminal, and Bryan Burkhart, Ernest’s brother, had gotten Anna Brown drunk before taking her out to Three Mile Creek, where Morrison fatally shot her. The prosecution turned Bryan into a witness for the state and he testified that Morrison shot Brown. Morrison was sentenced to life in prison for Brown’s murder, while Bryan Burkhart received immunity and was released.

Twenty Osage murders remained unsolved, though the murders came to an end with the Hale conviction. The tribe was happy the federal agents were able to solve the Smith, Roan and Brown murders, but they were not happy that the bureau did not investigate the other unsolved murders and disappearances. In all, more than 60 wealthy, full-blooded Osage were reported killed from 1918 to 1931. Newer investigations indicate that other deaths during this time period could have been murders that had been covered up.

The end result was that 25 percent of the Osage tribal mineral rights ended up in the hands of non-Osage, who were either White attorneys or businessmen who had been appointed guardians of tribal estates. Oil rights had been 100 percent in Osage tribal members’ hands when the killings began.

In an attempt to stop the murders, Congress in 1925 passed a law prohibiting non-Osage from inheriting headrights from Osage people who had half or more tribal ancestry.

Killers of the Flower Moon

Apple Studios’ Killers of the Flower Moon, based on David Grann’s award-winning New York Times bestseller, was released nationally on October 20, 2023. Directed by Martin Scorsese and starring Leonardo DiCaprio, Lily Gladstone, Robert De Niro and Jesse Plemons, the epic film about the reign of terror on the Osage Nation in the 1920s has received critical praise for its poignant retelling of this shameful chapter in American history.