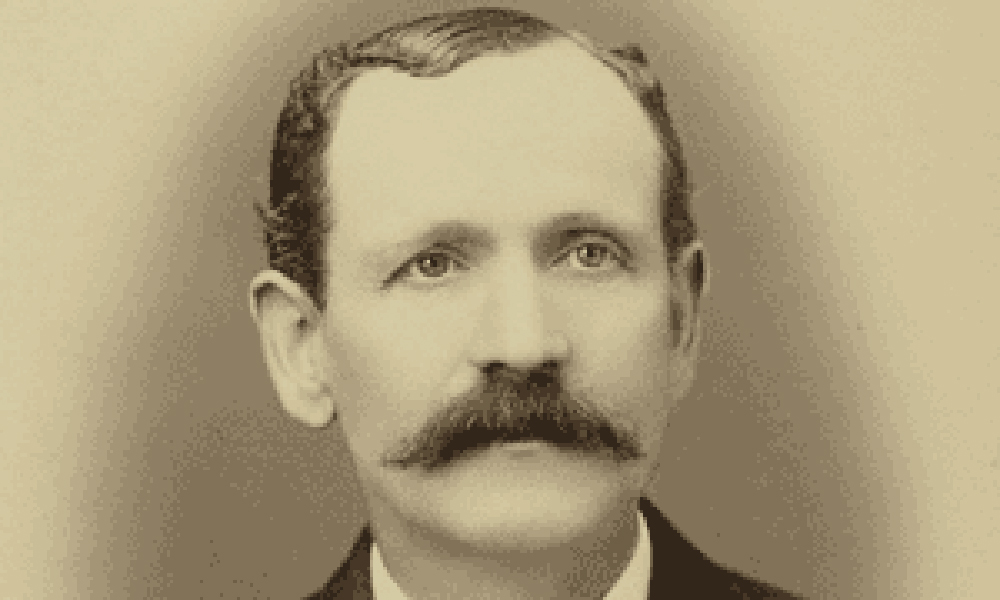

James Butler “Wild Bill” Hickok gets his likeness everywhere in Abilene, Kansas, where he served as lawman in 1871.

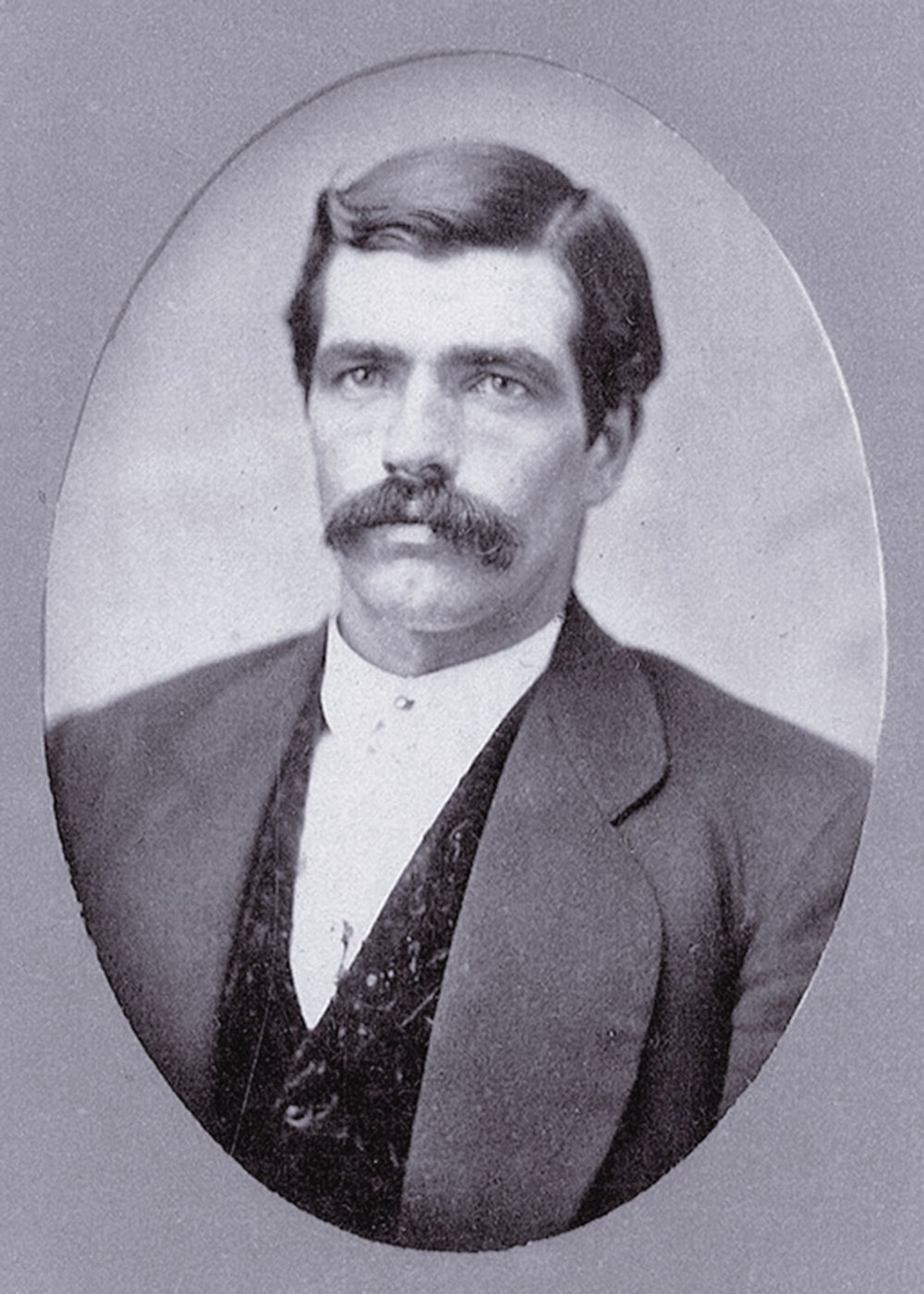

But his predecessor, Thomas James Smith, while not completely forgotten, is certainly overshadowed—even if Smith earned more respect from locals, and Texas cowboys, than that “Prince of Pistoleers.”

Following “Bear River” Tom Smith is no easy task.

Most believe he hailed from New York City. In 1904, C.C. Kuney, police magistrate during Smith’s tenure in Abilene, had “a faint impression” that Smith served in the 69th New York Infantry during the Civil War. But Kuney, in that letter to The Abilene Chronicle, was certain that Smith had left New York for Montana, “where he followed mining” and wound up as a lawman on “some of the worst towns” along the Union Pacific’s lines.

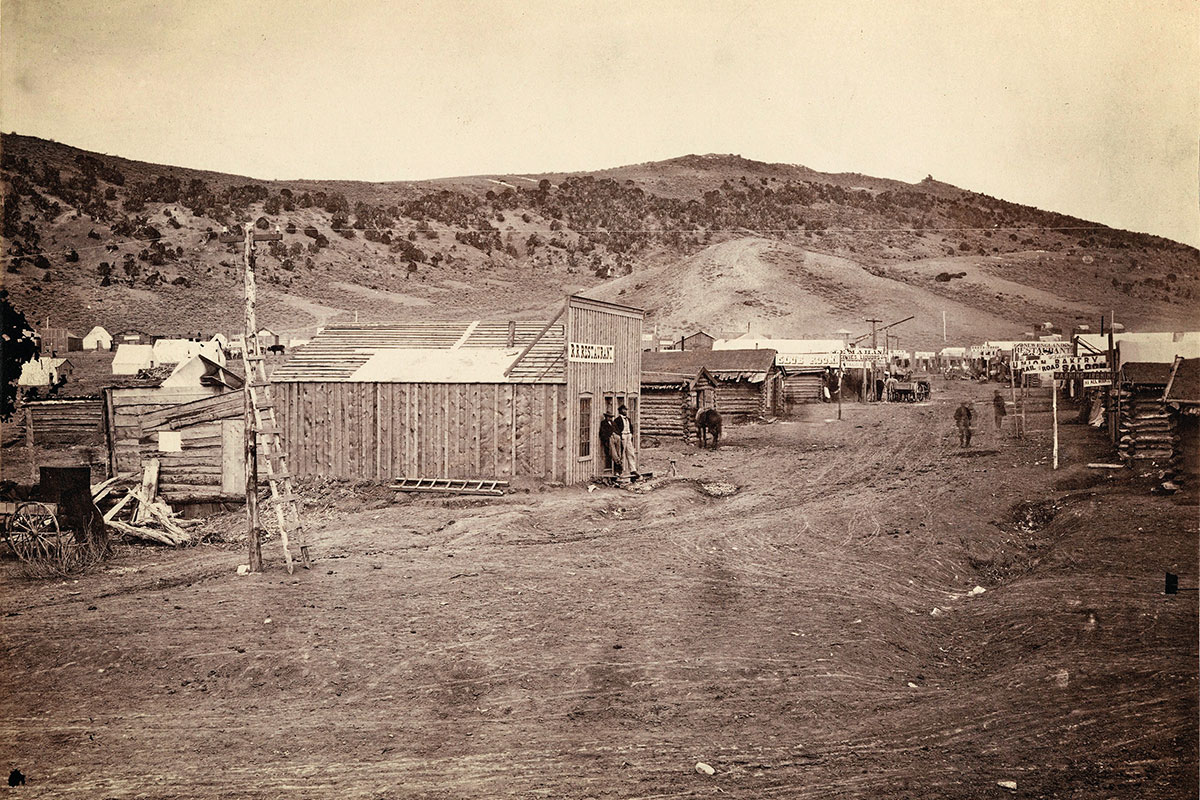

Smith might have been born in 1840 in New York City, where he became a boxer and a lawman before heading westward. He found work on the Union Pacific Railroad, which took one Tom Smith to the now-vanished hell-on-wheels called Bear River City, which sprang up roughly ten miles southeast of present-day Evanston, Wyoming (Unita County Museum).

In November 1868, UP graders rioted at Bear River City. Legh R. Freeman, a virulent ex-Confederate publishing a virulent newspaper, The Frontier Index, called for three accused murderers to be lynched. Instead, a mob attacked the jail, freed at least one prisoner, burned down the jail and torched the newspaper office. Troops from Fort Bridger brought order to what was left of the town. Some accounts say that Smith helped put down the riot, but contemporary sources called Smith “a most desperate character” who led the riot. In December, Salt Lake City’s Deseret Evening News reported that Smith was sent to the penitentiary in Salt Lake (today’s Sugar House Park). Or, if you buy Herman Francis Reinhart’s Recollections, Smith “was smuggled onto the stage and run in towards Salt Lake City by some of his city friends.”

The late historian Joseph G. Rosa wasn’t even sure if Bear River’s Tom Smith was Abilene’s Tom Smith. But ex-Abilene Mayor T.C. Henry wrote in 1904: “I did not understand at that time why [Smith] should be leading rioters, and I have never fully cleared up that. …I do know, however, that whatever part Smith played in those riots was to his credit.”

Smith wound up in Kit Carson, Colorado, where he was serving as marshal— at least that’s what Smith said when he applied for the marshal’s job in 1870. He got rejected. Abilene went with “home talent,” which wasn’t talented at keeping peace in a hell-raising cattle town. So Henry sent for Smith, then in Ellis, Kansas, and Smith took the job that spring (he also served as under-sheriff). His salary was $150 a month—later bumped to $225—plus a percentage of fines collected.

Smith banned the carrying of firearms in Abilene’s city proper, enforcing that law with his fists while riding a big horse named Silver Heels. “Whenever he would find a man still armed and violating the ordinance,” Stewart P. Verckler wrote in Cowtown–Abilene, “the Texan was likely to find himself held by the scruff of his collar with his feet dangling, as Smith relieved him of his side arms.”’

Later stories told of Smith bare-knuckling ornery Texas cowboys into seeing the error of their ways. Pretty good for a soft-spoken, slender, devout Catholic who stood under six feet tall. Peace came to Abilene—as peaceful as cowtowns could get—and Smith received a commission as a deputy U.S. marshal.

In late October, Andrew McConnell killed John Shea on Chapman Creek. McConnell turned himself in, and Moses Miles testified that the killing was in self-defense, so McConnell was released. Neighbors, however, suggested that Shea, who left behind a widow and three children, was not the aggressor. So Dickinson County Sheriff James McDonald asked Smith to go with him to bring in McConnell.

It’s no surprise that what happened on November 2 still isn’t clear. Resisting arrest, McConnell or Miles shot Smith in the chest. Smith was still fighting, so, the Chronicle reported, “Miles struck him on the head with a gun, felling him senseless to the ground, and seizing an ax, chopped Smith’s head nearly from his body.” At some point during the ruckus, McDonald fled.

“If the murderer is not caught and lynched forthwith,” The Kansas Weekly Tribune of Lawrence opined after learning of Smith’s murder, “it will be a disgrace to the locality.”

On Friday, November 4, Silver Heels—riderless—followed the hearse, with a pair of revolvers, a gift to Smith from the city, in holsters hanging from the pommel.

Miles and McConnell were captured November 5. A change of venue sent them to Manhattan, Kansas. Seeking the death penalty, prosecutors refused to accept guilty pleas from both men, which would have meant life terms, and tried the pair separately. On March 18, 1871, Miles was convicted of second-degree murder and sentenced to 16 years in the state penitentiary. McConnell then withdrew his not-guilty plea, pled guilty to first-degree manslaughter and was sentenced to 12 years.

“Thus ends one of the most horrible tragedies that has ever occurred in the State,” the Chronicle reported. “Twelve and 16 years in the penitentiary seem long periods, but the condemned ought to be thankful that they get off with even such sentences. Never during their natural lives can they atone for their great crime.”

Miles was pardoned after serving six years; McConnell was released in 1881.

the year in honor of its rich heritage as a Chisholm Trail cowtown. — Johnny D. Boggs —

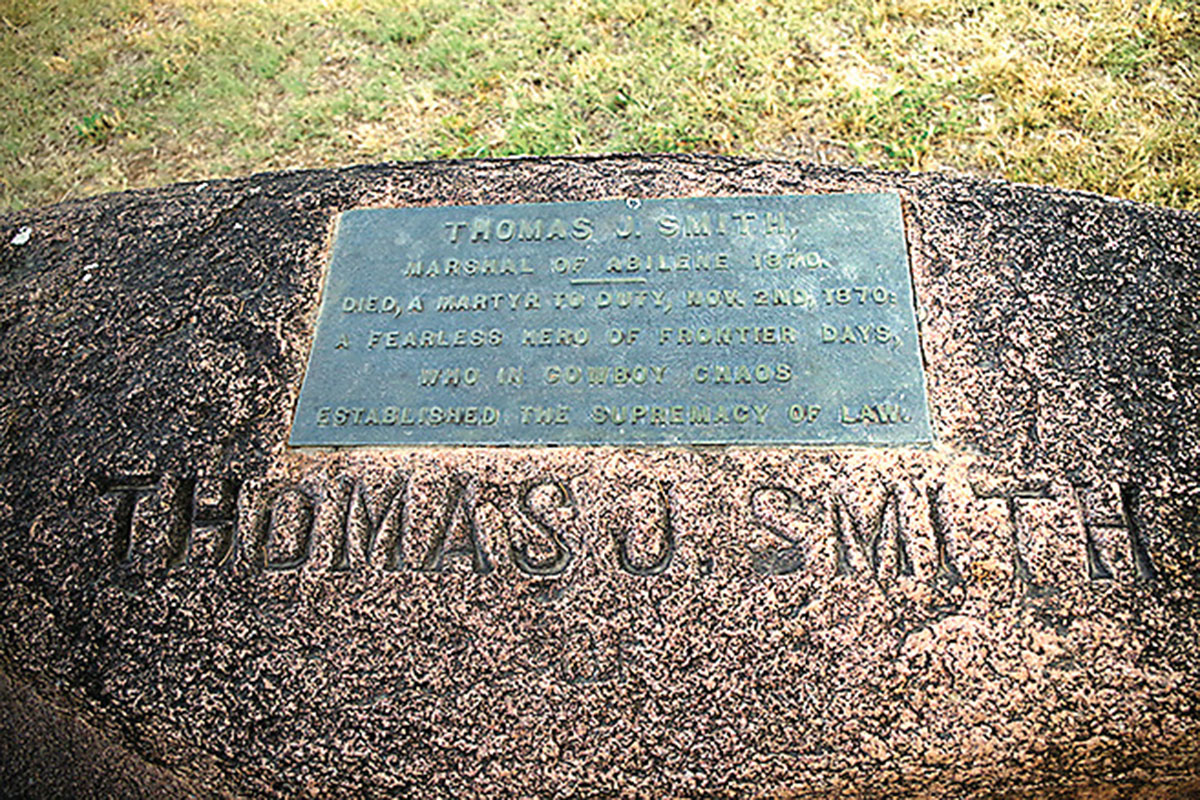

Abilene, of course, hired Hickok, who did things his own way—and paid a dear price when he killed gambler Phil Coe and, accidentally, his friend and deputy, Mike Williams, in 1871—and history left Smith in Hickok’s shadows. Yet the lawman with fists and grit is far from forgotten in Abilene. The Dickinson County Museum honors him as much as it honors Hickok and hometown hero Dwight D. Eisenhower. But it took 34 years before Tom Smith got his due.

On May 31, 1904—“an ideal Kansas day,” the Chronicle reported, the city of Abilene dedicated a new marker—a 4,480-pound red granite boulder from Oklahoma—at Smith’s grave, honoring “the intrepid marshal of pioneer days who gave his life to uphold the dignity of the law.”

Johnny D. Boggs’s latest novel, The Fall of Abilene (Center Point Large Print), follows John Wesley Hardin and Wild Bill Hickok in 1871 Abilene, Kansas.