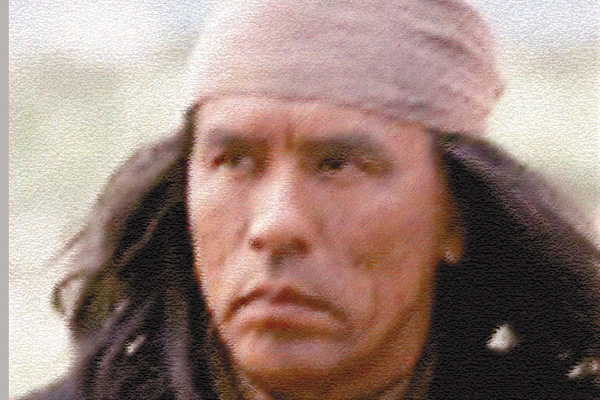

Santa Fe and Hollywood are a long way from Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma, but Cherokee actor Wes Studi has found a home in all three worlds.

Santa Fe and Hollywood are a long way from Nofire Hollow, Oklahoma, but Cherokee actor Wes Studi has found a home in all three worlds.

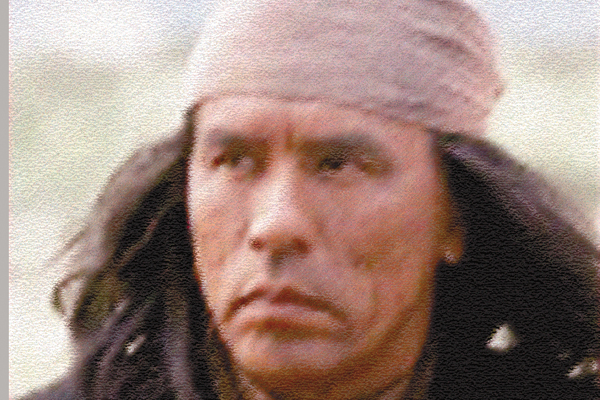

Many critics say Studi should have been nominated for Best Supporting Actor for portraying the vill-ainous Magua in The Last of the Mohicans (1992). He was equally unforgettable as a Pawnee in Dances With Wolves (1990), and his star turned in Geronimo: An American Legend (1993). His latest role is as Joe Leaphorn, Tony Hillerman’s taciturn Navajo detective, in Skinwalkers on the PBS Mystery series.

Studi is one of the most recognized and respected Native American actors of our time. True West caught up with him at his Santa Fe home. Soft-spoken and witty, he looked fit and relaxed, but there was an ever-present intensity in his eyes that made you think: Yeah, he would cut your heart out if you crossed him.

True West: I’ve read that you were born in 1946 and 1947. Which year was it?

Wes Studi: (Laughing). Well, I guess if I had a choice I’d pick ’47, wouldn’t I? Shave off one year. And I thank you for the choice.

TW: All right, I won’t push. You were in Vietnam in 1968. Any memories stand out?

WS: I got there right in time for the Tet offensive. We spent our first week there without doing anything, but all of a sudden there were a lot of people being airlifted out of there and they were running short so they finally sent in us new guys. We went immediately into urban guerrilla warfare, and that will definitely prepare you for just about anything.

TW: In The Last of the Mohicans, a number of people have said that movie had an authentic look about it, from the siege to the wardrobe.

WS: They went to great lengths to authenticate wardrobe and dress and styles, hairstyles, paint, things like that. The main characters who were on camera any extended amount of time, they went to a lot of trouble to authenticate the look. And it worked, as well as all those languages.

TW: How many languages did you have to speak?

WS: We couldn’t find anyone for Huron, for the language. I know there is, but they didn’t look as hard as they could. So I used a bit of Cherokee in some of the Huron languages that I had to speak. Delaware, Mohawk and French were the languages that I don’t speak. And of course, English and Cherokee. Cherokee shouldn’t have been in there. I probably shouldn’t tell you that.

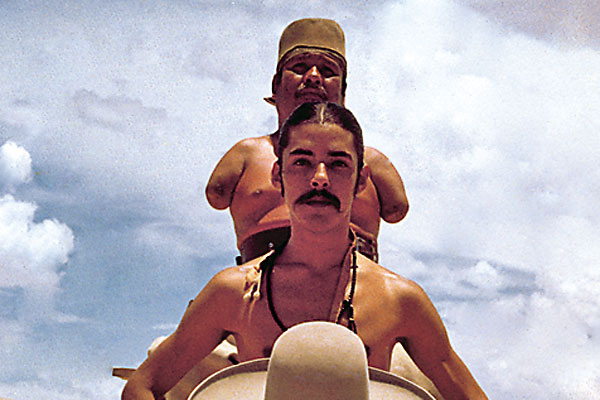

TW: How about in Dances With Wolves?

WS: That was really Pawnee. We learned that on tapes. They had a man there translate the English words, and we worked with language coaches.

TW: Is it tough to act in a language you don’t speak?

WS: Well, it’s an added dimension. You first of all have to know what this certain block of syllables is meant to convey. You need to have that in your mind and how to make the syllables as smooth as possible. Otherwise, you’re just saying syllables.

TW: What do you think of Russell Means?

WS: I think he has a presence. I’d like to see if he could act in venues other than camera work. I think a lot of times that’s the real test of an actor.

TW: How about Means as an Indian activist?

WS: Well, I think Russell served a great purpose at one time. I can’t agree with his current stand about defying the sovereignty of the Navajo Nation—when it’s a sovereignty that I understood him to be in support of in the old days.

TW: You were at Wounded Knee?

WS: I wasn’t one of the biggies, but I was there.

TW: Did you accomplish what you set out to do during that time?

WS: I think that we accomplished what was meant to be accomplished there. It solidified thinking in terms of moving toward a real sovereignty, which is something that we’re still doing, establishing sovereignty for the different nations of the Indians of the United States. I think that is the strongest outcome of the entire activism period. Young people began to grow up and began to think of themselves as people who could run their own lives and then, yes, their own governments.

TW: What’s your opinion of the state of the Indian nation today?

WS: It’s a broad subject because there are so many different levels that tribes in the states are at. Some have latched onto the gaming world and been very successful while others have latched onto it and been [moderately] successful and some haven’t but endeavor to become economically feasible in their own right. I think the overall outlook for the Indian nations of the United States is very positive in that it continues to build.

TW: Back to acting, what’s the difference between playing a fictional character like Magua and a historical character like Geronimo?

WS: There’s a certain amount of freedom that you have in creating a fictional character like Magua. You have a lot more room. You’re not restricted, and this may be a personal thing on my part, but coming through the activism years, people like Geronimo were icons. These were the people we looked up to. These were the leaders of the resistance that we looked up to and hopefully could be like. It’s kind of hard when you begin to learn the less-than-heroic aspects of their lives. And to bring that into a story that’s on film was kind of hard to do. Not all of his people loved him, that’s for sure. Geronimo didn’t have the greatest reputation as far as women went. He lived in different times—that’s not any kind of excuse—but the man has living relatives to this day, and some of them say that he was a great guy, a great man. And some say he wasn’t so great. Some say that he did good for the people, and some say that he only drug them down.

TW: What historical figure would you like to play?

WS: Ely Parker. He was a Seneca, and actually the man who wrote the terms of the surrender for the Confederates at the end of the Civil War. He was a friend of President Grant and he also became the first commissioner of Indian Affairs. And this was a time when Indians weren’t even citizens of the United States. He was more or less a self-taught engineer who did a huge canal in Rochester, New York. I think he was an extraordinary man for his time with a bittersweet or even sad end.

TW: Since we talked about a warrior in two worlds, how about Quanah Parker?

WS: I don’t think there was as much of two worlds in him. I think he made a conscious choice to be a Comanche, and then to become the chief of the Comanches. I think his mother made a lot of the choices for him.

TW: Stand Watie?

WS: Oh, I’ve got too much Cherokee baggage to play him. I don’t agree with what he was doing. I can understand because maybe he thought the Confederacy would win. But the Cherokees picked the British over the Americans and that proved to be a wrong choice, and the way Stand Watie treated his own people during the war, I definitely don’t understand that.

— Johnny D. Boggs