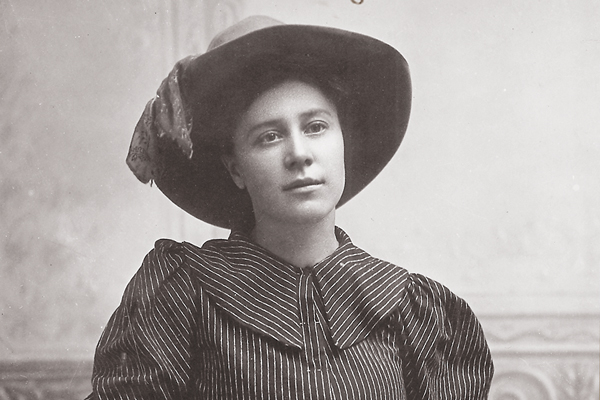

Rose of Cimarron, mystery woman.

Rose of Cimarron, mystery woman.

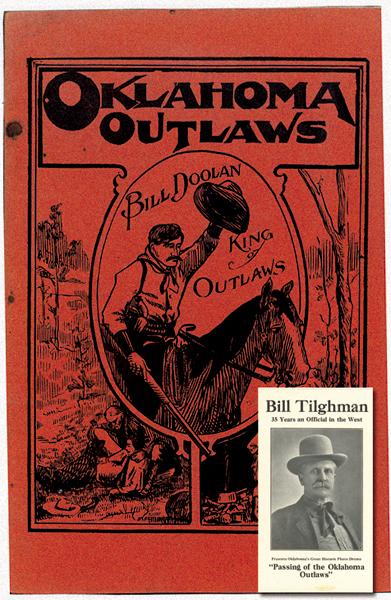

Rose of Cimarron was first introduced to readers in 1915 in a little red paper-covered book titled Oklahoma Outlaws. The book was prepared by a newspaperman using information supplied by Bill Tilghman, a respected lawman in Oklahoma Territory in the 1890s. It was sold at showings of the photodrama, Passing of the Oklahoma Outlaws, which was scripted primarily by Tilghman. In the book and movie portrayal of the Ingalls battle between 13 lawmen and six members of Bill Doolin’s gang, Rose of Cimarron makes a dramatic exit from the hotel, carrying a rifle through a hail of bullets to her wounded lover, outlaw Bitter Creek Newcomb.

This story was repeated in numerous books, with and without embellishments, for the next 37 years. The real identity of “Rose of the Cimarron” (which eventually became the most popular version of the title) was never revealed, supposedly because she had become a respected Oklahoma citizen and no one wanted to embarrass her. Finally, in 1952’s Desperate Women, author James D. Horan revealed that her real name was Rose Dunn, the sister of four brothers who lived near Ingalls and were alternately outlaws and lawmen. Horan did not know if Rose Dunn was still living in 1952—but she was.

Born September 5, 1878, Rose Dunn was four days short of her 15th birthday at the time of the Ingalls fight, not too young for romantic involvement in that era. She married for the first time in 1897 at the age of 19, and again in 1946 after the death of her first husband. Rose died in Centralia, Washington, on June 11, 1955, as Mrs. Richard Fleming. After Rose’s death, her widower told an interviewer that he first met Rose at an Ingalls square dance when he was 17 and she was 16. “I first heard her referred to as Rose of Cimarron in 1895, soon after I came down here [to Oklahoma]. They called her that, but not because she was a bandit queen. She was a superb horsewoman,” Fleming said. “She was a true friend of the outlaws and never betrayed them, but she was never the sweetheart of any.”

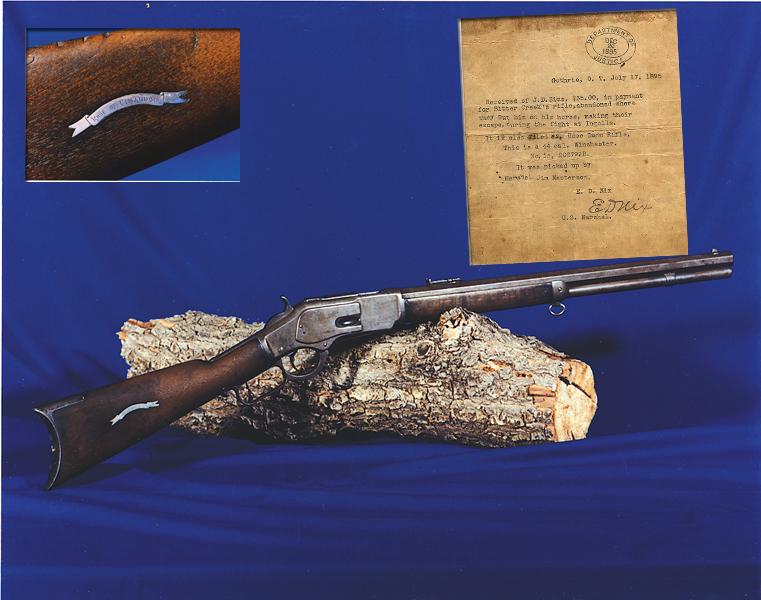

So there really was a Rose of Cimarron, and she was a “friend of the outlaws.” Glenn Shirley, a respected author of books on the Oklahoma outlaws and lawmen, initially accepted the story of Rose in the Ingalls gunfight (Toughest of Them All, 1953) but eventually came to the conclusion she was not there. Shirley couldn’t find one mention of Rose, or any other woman, in newspaper accounts of the gunfight. When an 1873 Winchester with the engraved “Rose of Cimarron” plate in the stock and an accompanying note signed by U.S. Marshal E.D. Nix was revealed to Shirley, he expressed no doubt that the note and rifle were authentic. However, he theorized that the gun was received by the marshal’s office after Newcomb’s death at the hands of the Dunn brothers (for the reward money) on May 2, 1895, which was a year and a half after the Ingalls battle. Yet, Nix states in the note that the rifle was picked up on an Ingalls street and was the one Rose Dunn took to Newcomb. Nix didn’t sell the rifle until two years after the September 1, 1893, gunfight.

Shirley also suggested that the engraved “Rose of Cimarron” silver plate was placed in the stock at a later date and that the rifle may have been one of many that toured with Tilghman and his movie. It is extremely unlikely that Rose Dunn would have put the plate on the gun. Most likely, J.D. Sims, who purchased the rifle, or Tilghman added the plate. In any case, gun experts agree that the plate is quite old.

Tilghman’s widow Zoe said she knew Rose Dunn. Her husband didn’t make up the tale of Rose in Ingalls, she said, however, the story that surfaced later claiming Rose was arrested and tried isn’t true (and it wasn’t mentioned in Tilghman’s 1915 book).

In the early 1940s, Chris Madsen, a deputy marshal who served with Tilghman in Oklahoma Territory in the 1890s, searched for Rose Dunn “to get a contract for the production of a motion picture to be entitled, Rose of Cimarron.” Madsen didn’t locate Rose, who had probably moved to Mountainair, New Mexico, by that time. He probably wouldn’t have gotten Rose to sign, as Rose’s second husband said after her death: the stories “caused my wife a great deal of embarrassment and forced her into virtual seclusion.”

So, what is the truth about Rose of Cimarron? If we are to believe the note that Nix signed in 1895, Rose Dunn was in Ingalls at the time of the gunfight and did take a rifle to Bitter Creek Newcomb after he was wounded. Newcomb ended up being too badly wounded to use the rifle, and he dropped it when he escaped on horseback.

Newspapers may not have reported Rose’s involvement for the same reason that Tilghman and others did not disclose her identity until years later—they did not want to embarrass the young girl. After all, Rose was the stepdaughter of Dr. W.R. Call, a prominent resident of Ingalls. She lived with her parents in their home, next door to the OK?Hotel, the center of the gunfight. Rose spent a lot of time there and at her brother’s place, a few miles away near the Cimarron River. Ingalls and the Dunn home were known hangouts for the Doolin Gang, and Rose’s rumored paramour, Newcomb, was later killed at the Dunn home.

More than 20 years later, Rose of Cimarron’s role in the Ingalls gunfight was told in a book and movie, with the usual exaggeration and dramatization. (After the movie’s release, a “former outlaw” from Tulsa wrote Tilghman, “Did you know … Rose of Cimarron lives here [Tulsa]? She still retains some of the beauty that caused her to bear the name.” He went on to spin some preposterous tales about Rose.)

Conclusions:

• Rose Dunn Fleming wouldn’t have been so embarrassed about her role in the Ingalls gunfight if there wasn’t some basis of fact.

• Bill Tilghman would not have reported the story if there was not some basis of fact.

• Chris Madsen, who often questioned Tilghman’s accounts, would not have searched for Rose Dunn so he could obtain permission to make a movie about her if there was not some basis of fact.

• U.S. Marshal E.D. Nix would not have written a receipt for the rifle if there was not some basis of fact.

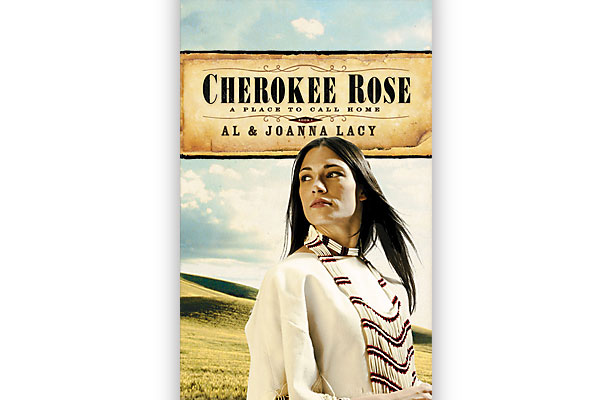

Is the photo really of Rose Dunn, the Rose of Cimarron? A comparison with a photo of Rose from the 1950s, when she was in her 70s, does not rule out that possibility.

A copy of the original cabinet card appeared in the 1890s with the name Jennie Metcalf penciled in at the top. In Oklahoma outlaw history, there really was a Jennie Metcalf (although her name was actually Jennie Stevens, alias Jennie Midkiff, alias Little Breeches). But a photo of Jennie and her partner Cattle Annie shows that Jennie bears no resemblance to Rose of Cimarron.

The Rose of Cimarron photo is definitely of the period, as it was grouped with many outlaws in a composite photo that was probably made between Doolin’s death in August 1896 and mid-1898, when Little Dick West was killed a few miles from Guthrie (his death photo does not appear in the composite).

Who is the attractive girl in the photo if not Rose of Cimarron?

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy University of Oklahoma –