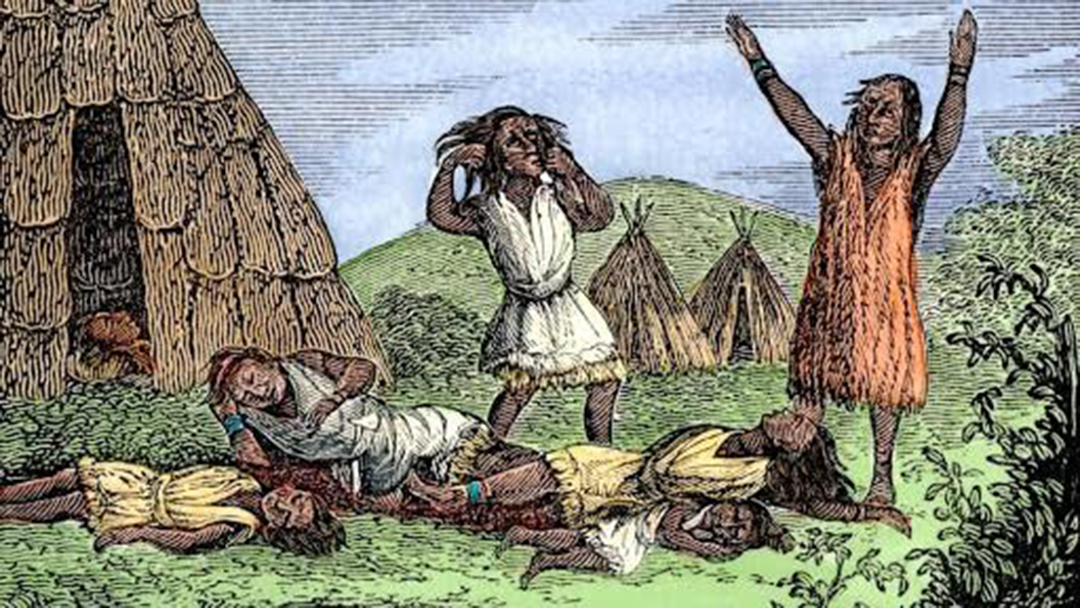

Smallpox was the scourge of the West, especially to the Indians. It attacked whole tribes and left few survivors. It has afflicted Native Americans since it was carried to the western hemisphere by the Spanish in the 16th century. It was particularly deadly to the Plains Indians as none of these tribes had been exposed or developed an immunity.

The Indians called it “Rotting face” for the pustules that broke out on the skin. It could be contracted human to human by sneezing, coughing and through the clothing of a person infected. There had been a catastrophic epidemic in the 1781 and 1801 on the Plains that nearly decimated the Mandan, but the 1837 epidemic was the coup de grace.

The epidemic began in 1836 and lasted until 1840 but it reached its height in the spring of 1837. An American Fur Company steamboat the St. Peters, was plowing its way up the Missouri River to a trading post called Fort Clark. On board were some infected passengers, including three Arikara women, who got off the boat. Why Captain Bernard Pratt skipper of the St. Peter refused to quarantine those suspected of being affected would kill thousands is an enigma.

That evening a large celebration was held in the nearby Mandan village. The next morning the St. Peters headed upstream for Fort Union bringing with it the deadly virus everywhere it stopped. The only explanation for Pratt’s action was greed. He was more interested in avoiding any delays in his schedule.

The Mandan suffered the worst losses. The smallpox spread quickly through the area. In July 1837 the Mandan population was about 2,000 and by October the survivors numbered less than thirty. Francis Chardon, commander at Fort Clark for the American Fur Company, wrote: “Only twenty-seven Mandan’s were left to tell the tale.”

More than 17,000 Native Americans along the Missouri River perished. Some tribes such as the Mandan, became extinct. The smallpox epidemic of 1837-38 all but wiped out the Mandan and severely reduced the Arikara and Hidatsa who also lived in fortified villages along the Missouri river and farmed corn, beans and squash, with buffalo hunting part time. The buffalo-hunting tribes who didn’t farm and whose isolated bands weren’t hit as hard by the epidemic.

A longboat heading up the Marias River to Fort McKenzie carried the dreaded disease to the Blackfeet. Up to then they had been one of the most warlike of the western tribes and the nemesis to the American Mountain men who tried to trap beaver in their domain. It is estimated that two-thirds of the tribe was wiped out. About half of the Assiniboine and Arikara, a third of the Crow and a quarter of the Pawnee perished by 1840. The Plains Indians upstream from the Arikara had been denied access to the 1832 federal vaccination program by the Secretary of War. Ironically, that was the same year steamboats began hauling supplies and furs for the trading posts on the Missouri River.

A trader at Fort Union wrote, “such a stench in the fort that it could be smelt at a distance of 300 yards.” Bodies were buried in mass graves. Some were tossed into rivers furthering the spread as the body remains infectious after death.

Over the next three years the epidemic traversed thousands of miles reaching from California and up the Pacific coast all the way to central Alaska.

During my 40 some professorial years I used to lecture on the Great Smallpox Epidemic of 1836 and told a story of a great warrior who watched helplessly as his parents, wife and children succumbed to rotting face. He war-painted his pony and himself, grabbed his lance, rode out to the top of a small butte, looked up to the sky and challenged the cowardly disease to come out and fight him man to man like a real warrior.