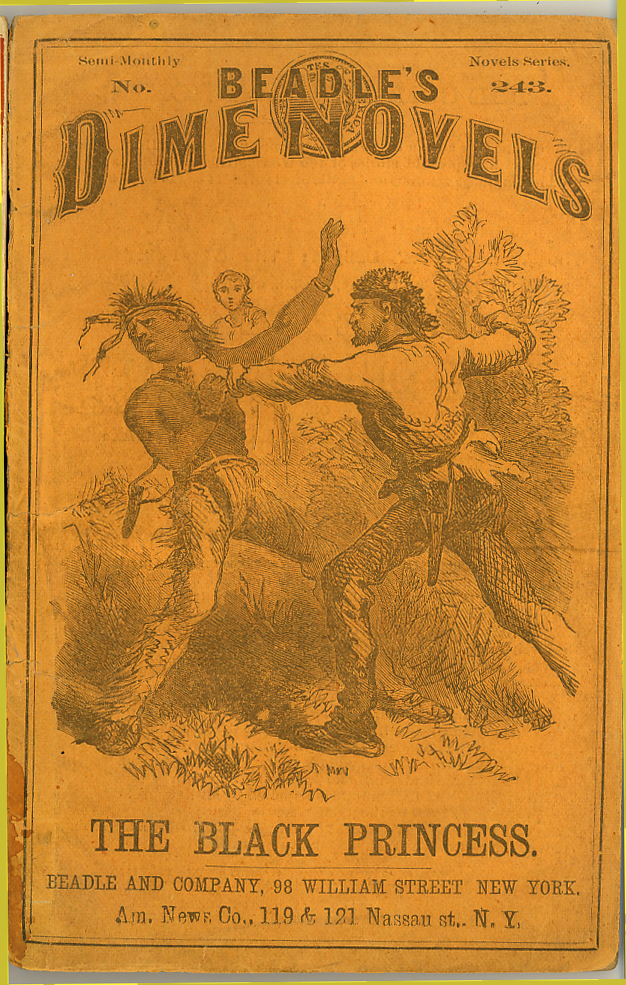

Dime novelists fed the voracious public appetite for daring exploits and hero-making. Much of the violent image of the West was due to pulp westerns published by Beadle and Adams. In 1869, Edward Z. C. Judson, writing under the nom de plume, Ned Buntline, went west to persuade Major Frank North, leader of the legendary Pawnee scouts, to appear in a Wild West show. North was a legitimate western hero. He was no fan of Buntline’s pulp novels and turned him down cold. Undaunted, Buntline found a young man named Bill Cody sleeping under a wagon. They struck up a fast friendship and Ned returned to the East where he cranked out a series of dime novels heralding the adventures of Frank North but used Cody’s name. The legend of Bill Cody or “Buffalo Bill” was born. Then Buntline persuaded Cody to participate in a stage play. Soon after, Cody formed his own Wild West show and, as they say, the rest is history.

In 1887, dime novelists introduced Buck Taylor as the “King of the Cowboys.” He and others of his ilk became the original gunfighter heroes of folklore.

In 1903, Owen Wister wrote the prototype of tight-lipped heroes, “The Virginian.” That same year Edwin S. Porter filmed “The Great Train Robbery,” the first motion picture with a story, in the wilds of New Jersey. Audiences loved it and demanded more. Ironically, at the same time, real outlaws were still robbing trains out west. Two desperadoes, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid may have visited a movie theater in New York City and saw themselves portrayed on the silver screen in Edwin S. Porter’s “Great Train Robbery.” The two outlaws were robbing a train and shooting passengers indiscriminately. That must have been a particular shock to Butch, since he’d never shot anybody. They also saw themselves gunned down by a posse at the movies’ end.