During the 1850s no sooner did the Army Corps of Topographical Engineers survey wagon roads to the Pacific than emigrants began painting their wagons and heading West. It was the largest mass migration of pilgrims since the Children of Israel set out in search of Canaan. Those traveling the all-weather routes in Arizona before they reached the Promised Land believed they passing through the gates of hell itself.

One such family was that of Roys Oatman, his 38-year-old wife Mary Ann, who was 8 months pregnant, Lucy 16, Olive 13, Mary Ann 8, Roys Jr. 5, Charity 3, and Roland two.

The Oatmans were members of Mormon group led by James Colin Brewster who split away after Brigham Young. Brewster believed a new Zion, called Gashan awaited the faithful at the mouth of the Gila and Colorado Rivers.

Their wagon train kept breaking off into smaller groups and at Maricopa Wells, near the Pima Indian villages in early 1851, Roys Oatman decided to go on alone. Contrary to the movies, bands of hostile Indians rarely attacked a large party of wagons, although small ones were always fair game.

The Oatmans stopped to camp on a small plateau west of today’s Gila Bend. While making camp a group of nearly twenty Western Yavapai Indians rode in. Roys decided to give them anything they demanded in hopes they would go away. Being generous was, to the warriors, a sign of weakness. They whipped out war clubs and attacked the family killing ten, including Mary Ann’s unborn child. The only survivors were Lorenzo who was badly beaten and thrown over a bluff and left for dead. Mary Ann and Olive were carried off.

When Lorenzo regained consciousness, he saw the carnage and walked back to Maricopa wells. Meanwhile, the two girls forced to walk barefoot some 90 miles to the Yavapai camp in the remote desert further north where they were enslaved and brutally treated before being traded to the Mohave where they were taken in by the kindly chief and his wife. Soon after they adopted into the tribe. During a severe famine in 1854 Mary Ann died of starvation.

In 1856, a Quechan from the Yuma Villages came to the Mohave and gave warning that thousands of American soldiers were planning to converge on the Valley and slaughter them all if they didn’t set Olive “free.”

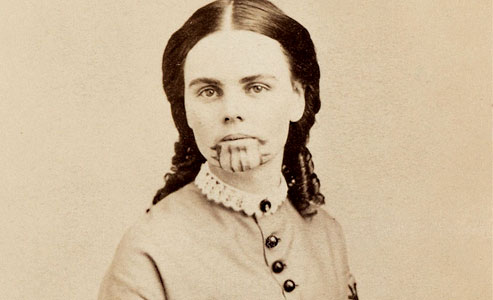

The Mohave chief reluctantly agreed to send Olive to Yuma. His daughter accompanied her on the trip. As with custom of Mohave women when they reach the age of marriage, they are tattooed. By this time Olive was eighteen-years old, well past the age when most were married. There’s good reason to believe Olive was married and gave birth to two children.

When they reached the outskirts of Fort Yuma, Olive, wearing a birch bark skirt and naked from the waist up, insisted they bring her a dress before returning to white society. At Fort Yuma, Olive was reunited with her brother Lorenzo, who’d never given up hope of finding her.

That same year a Methodist minister named Royal Stratton wrote a sensationalized book, the Captivity of the Oatman Girls that become a best seller. Stratton’s wild, hair-raising tales were mostly conjured up in his fertile mind. He was careful to avoid the subject of whether or not she married and had children.

Many lurid tales were told about Olive including the poor girl died in an insane asylum as a result of her ordeal. Truth is she lived a long and productive life. In 1865 she married a lawyer named John Fairchild and died in Sherman, Texas in 1903. And, she never had her tattoos removed.