Willie B. Rude vs. Apache Raiders

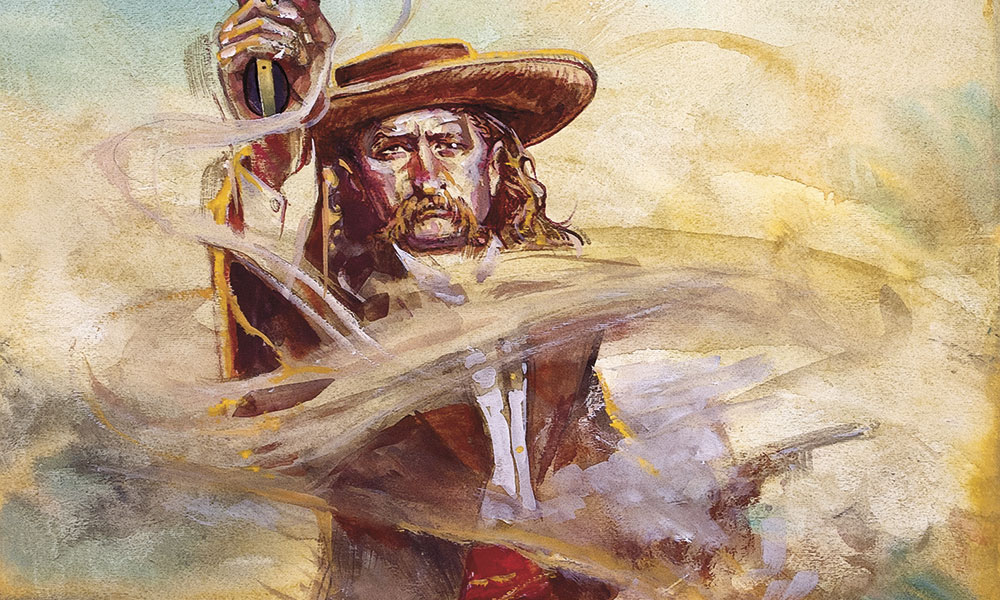

Against overwhelming odds Rude reloads with deadly efficiency.

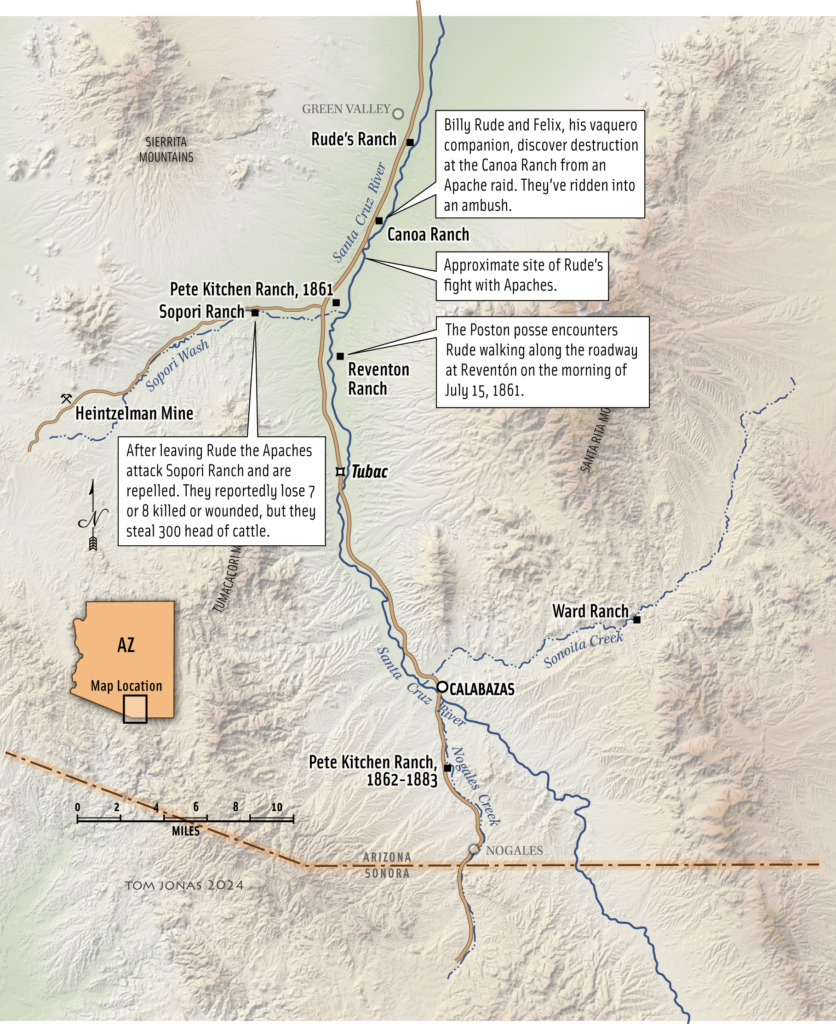

Map by Tom Jonas. Based on the research of Greg Scott.

July 14, 1861

An American ranchero named Billy Rude, along with a Mexican vaquero named Felix, are riding from Tubac, Arizona to retrieve some horses which Rude had left on his abandoned farm, after a series of very aggressive Apache raids.

The farm is about 18 miles from Tubac, on the road to Tucson. Riding through Canoa, a stockade inn, 14 miles from Tubac, they meet two Americans who were in charge of the place cooking dinner, Rude and his Mexican helper told the two they would return with their horses for dinner. After a half-hour ride and successfully rounding up the horses, they return to Reventon, where they secure the loose horses in the corral, and then turning toward the inn, they spy a bloody shirt hanging on the gate. Approaching the dwelling, they spot a large party of Apaches (estimated at about 100 in number) lying low on their horses about a hundred yards off the road. They put the spurs to their horses and take off for Tubac with the Apaches in full pursuit. About a mile from the inn, Rude’s horse started giving out, and the two split up with Rude striking off the road toward the mountains.

Finding his horse failing, and having an arrow through his left arm, Rude left the road, hoping to make it to a thicket he remembered having seen on the trip up. With the attacking Apaches about 200 yards in the rear, Rude threw himself off his horse and took cover in the thicket. He later said it was very dense, with a narrow entrance leading to a dry mud-hole, or charco, in the center. Lying down, he spread his revolver cartridges and caps before him, and broke off the arrow shaft in his arm, painfully pushing it through and out, then buried his profusely bleeding elbow in the damp earth to stanch the bleeding. By then the Apaches had surrounded his leafy location, surrounded the thicket and began volley after volley into the defenseless position. A steady aim of the old frontiersman brought down the first Apache who charged the thicket. Each succeeding attacker met the same fate, until he had fired six shots. Then, believing him to be out of bullets, the Apaches charged with a loud yell. But the cool ranchero had loaded after each shot, and a seventh ball brought down the leader of the charge and then the eighth one brought down the attacker behind him. Volley after volley was fired into the thicket in the hopes of killing Rude, but he was tucked down into the dirt and survived the fuselage. The Apaches tried another charge, but Rude brought down another Apache and so they yelled at him: Guierrmo—Come and join us; you are a brave man and we’ll make you a chief.”

Rude laughed and yelled back, “Oh, you devils, you! I know what you’ll do with me if you get me!” A moment went by, then Rude heard a loud shout: “Sopori! Sopori!” the name of a neighboring ranch and the entire attacking party rode off.

The intense battle is over and now Rude got ready for a long walk.

A modern photo taken at the battle site of the possible mesquite thicket Rude may have sought refuge in. Photo by Bob Boze Bell

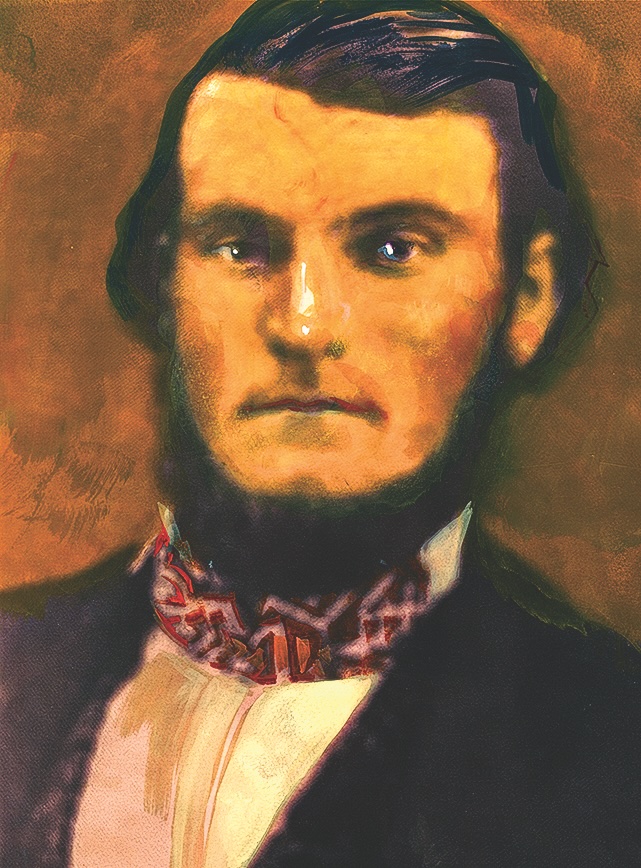

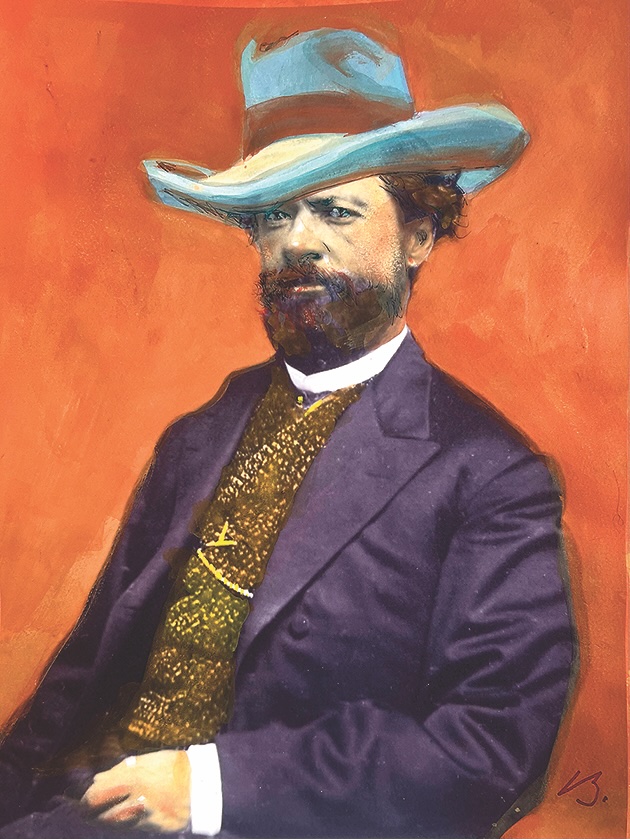

The King of Santa Cruz Valley

In addition to being the leader of the Sonoran Mining Expedition near Tubac which was capitalized with a $2 million secured investment and proceeded to produce an alleged $3,000 per day. Charles Poston was known as “the Colonel” and he printed his own money and officiated marriages and divorces and baptisms of children and he was the acting promoter and mayor of the place (see quote below) until Bishop Lamy in Santa Fe came to investigate. Allegedly, a payoff, I mean—a donation!—of $700 sanctified the unions. Poston also surveyed the townsite of Colorado City (later Yuma) and sold it for $20,000 before returning to San Francisco.

“We had no law but love, and no occupation but labor. No government, no taxes, no public debt, no politics. It was a community in a perfect state of nature.”

—Charles Poston, on the Santa Cruz Valley

A Rude Map of The Fight

Rude’s Reloading Layout

We asked our gun editor, Phil Spangenberger to walk us through the steps Rude had to take in order to reload his Colt after each shot.

In the mesquite thicket that Rude holed up in, he probably had his defensive layout looking something like this. After each shot was fired and the Apaches temporarily backed off, he wisely reloaded his six gun, keeping it ready for any onslaught his attackers might throw at him. To reload his caplock six-shooter he’d have to first bring the revolver to the half-cock position and manually rotate the cylinder so the now empty chamber was located just to the right of the barrel assembly, allowing him to pour a fresh charge of black powder (contained in his pistol flask at left on belt pouch) into the fired chamber of the gun’s cylinder.

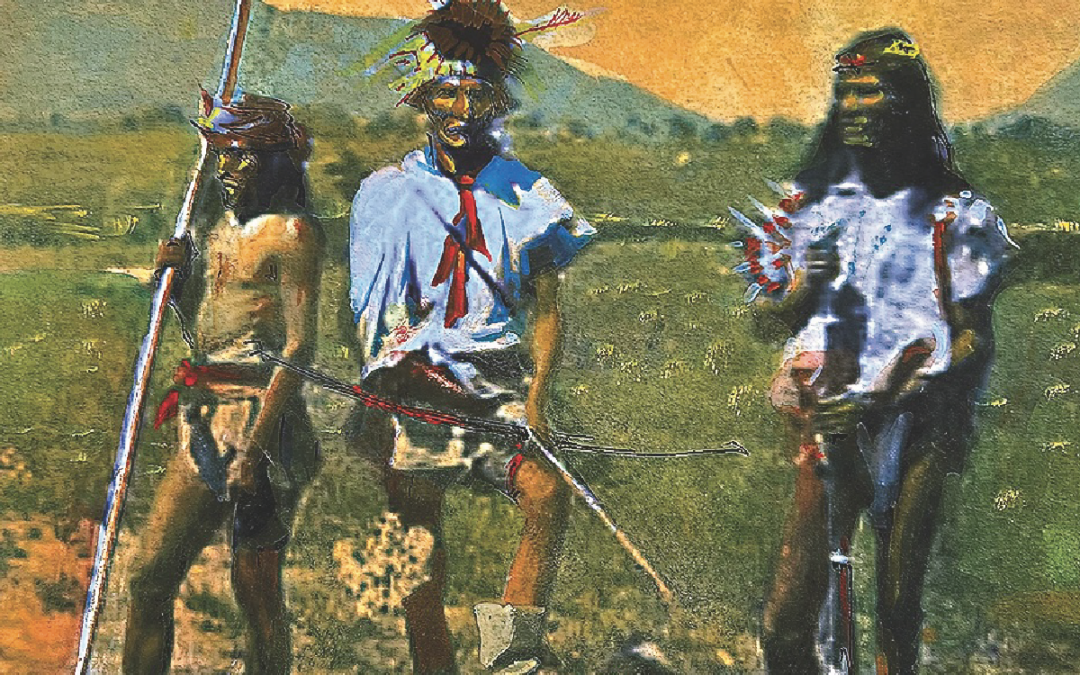

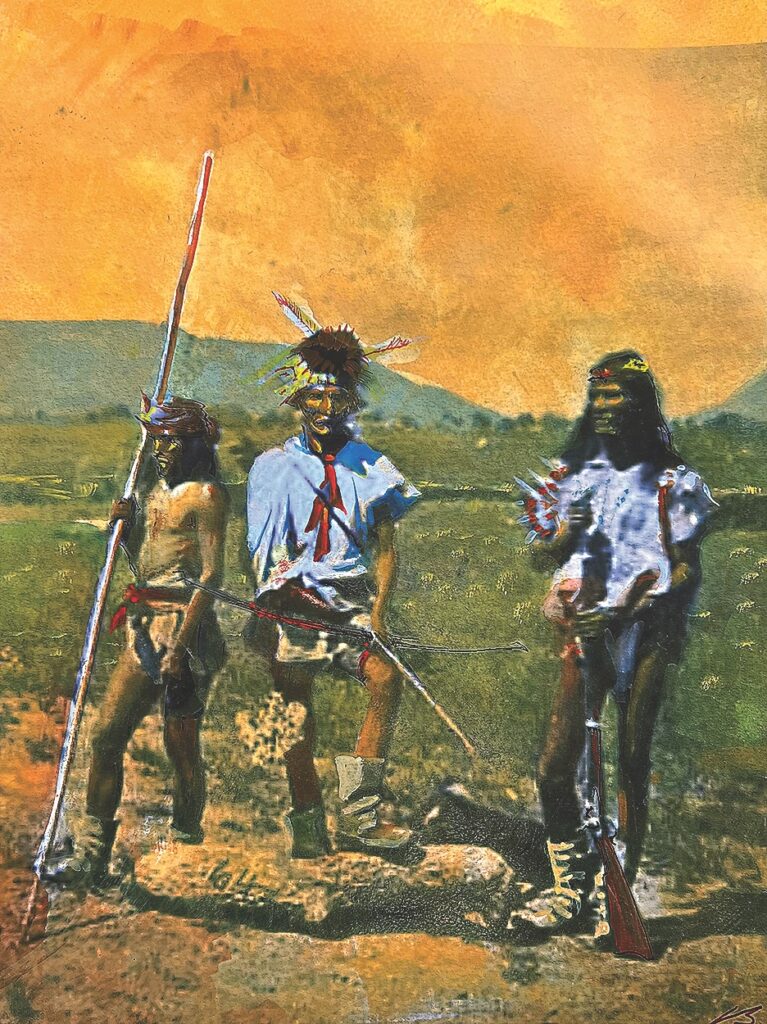

Although this illustration is based on an 1873 photograph of Apache warriors, this is likely how they were armed against Rude in the 1861 era: the trusty Apache lance, bows and arrows and single-shot long guns. it’s still amazing he even had a chance.

Then he’d take a lead pistol ball from the small pouch (fringed buckskin bag) where extras were carried, place the ball over the powder in the chamber, then using the under-barrel loading lever, seat the ball firmly over the powder charge. Once the ball had been seated, he’d rotate the cylinder to the cutout capping portion of the frame so he could place a small copper percussion cap, taken from the little round cap box (seen just above the buckskin pouch) and thumb press it over the empty nipple at the rear of the revolver’s cylinder. He then had his smoke wagon fully loaded and ready to greet any of his attackers. It takes longer for an experienced six-gunner to write this caption than to accomplish the loading of a single, or maybe even a couple of fired chambers in a cap-and-ball six-gun…as the Apaches found out!

—Phil Spangenberger

The upstart settlers called his new region “The Purchase” short for “The Gadsen Purchase.”

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Rude’s companion, the vaquero Felix made it safely back to Tubac, where he related this harrowing escape to Colonel Poston and Charles Pumpelly.

In the morning Poston led a heavily armed group out to bury the bodies and search for survivors. One of the posse members, Pumpelly relates that to their great surprise the first man they met was Rude, walking with his arm in a sling.

Not long after the Apache-mesquite fight near the Canoa Ranch, Rude and the other American rancheros had to abandon the Santa Cruz Valley for safer climes, and Rude ended up along the Colorado River, about 40 miles north of Yuma where he established his Rancho de los Yumas and began farming and raising cattle. He reportedly did quite well for some time, but on April 29, 1870 he and his ranch foreman, Alex Poindexter, crossed the river to pay Indian woodchoppers and on the way back, their raft hit a snag and Rude drowned. The foreman claimed he clung to the raft and made it to safety. After Rude’s death, rumors of hidden gold brought out the treasure hunters who picked at his walls and dug up the floors until only a shell of the house remained.

After a twenty year career in Washington and hopscotching around the globe, Charles Poston settled in Florence, Arizona and tried to build an eternal flame memorial on the nearby hillock. When that failed he moved to Tucson and became a lecturer and writer and after a few more government jobs he ended up in Phoenix in the 1890s where he sank into obscurity. The Territorial Legislature came to his rescue and provided him with a $25 month pension and increased it to $35 a month. Poston died of a heart attack in 1902. He became known as the Father of Arizona.

Recommended: The account of the fight was first published in a book, “Across America and Asia,” in 1869 by Raphael Pumpelly, a mining engineer who was in the small, five man posse led by Poston who encountered Rude at Retention after the fight. It contains the most accepted version of the Rude fight.