May 3, 1886

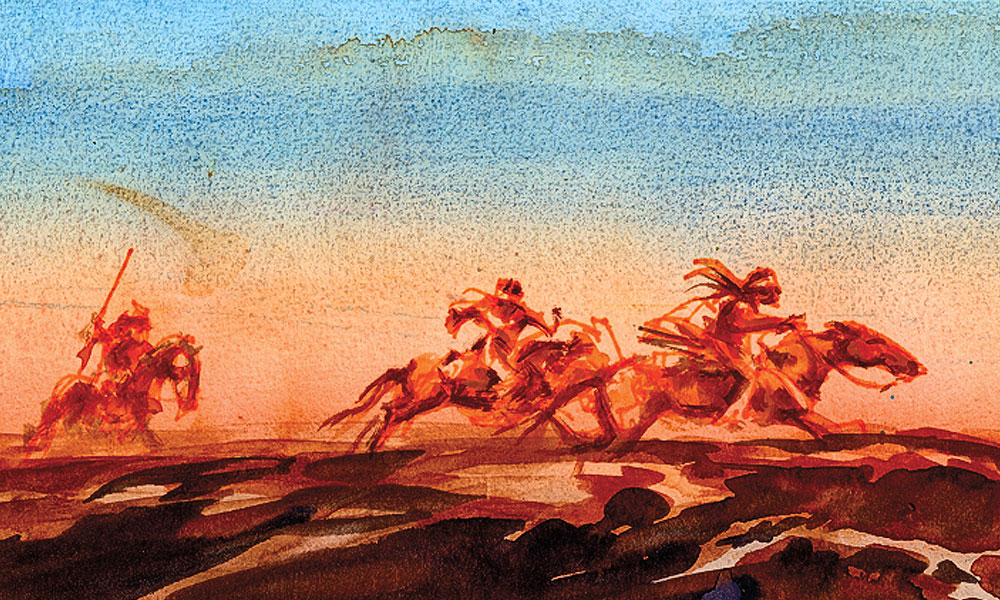

A few dozen elusive Apache holdouts, led by the intrepid holy man-warrior, Geronimo, are being pursued along the Arizona-Mexico border by nearly one-quarter of the United States Army.

Among the units hot on the trail of these last resisters are black troopers and their white officers of the 10th U.S. Cavalry. Captain Thomas C. Lebo commands Troop K as they finally close in on the Apaches in Sonora, Mexico, on May 3. The departmental commander would later laud the “great bravery” of Lebo’s horse soldiers during “this spirited engagement” that took place “against an enemy on ground of their own choosing, among rugged cliffs almost inaccessible.”

“The Indians held their ground and made an attempt to get our horses,” reported Lt. John Bigelow Jr., in the February 1887 edition of Outing. But these efforts were “frustrated by a covering force and a detail sent to drive the herd to the rear. Each side in the fight numbered about thirty men. Three Indians were seen to fall and to be dragged back out of fire, a pretty sure indication that they were killed or mortally wounded.”

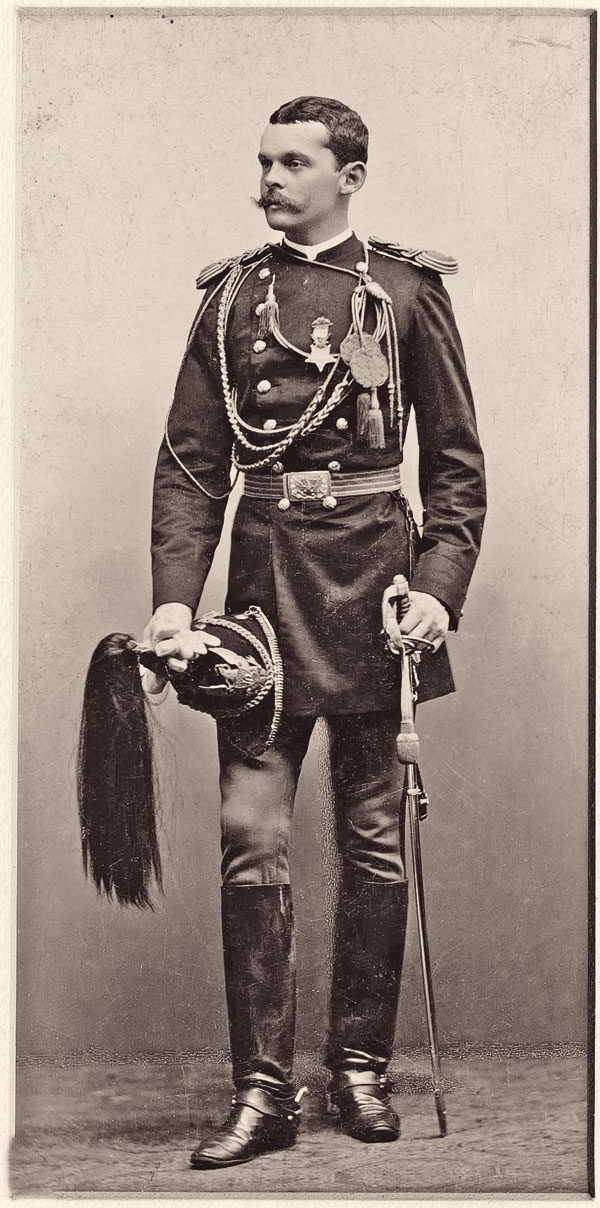

But the Apaches struck down Troop K forces too, killing Pvt. Joseph Hollis, while another soldier, Cpl. Edward Scott, “was severely wounded and lay, disabled, exposed to the enemy’s fire….” In a selfless act of courage, Lt. Powhatan H. Clarke, Capt. Lebo’s second in command, carried Scott to safety.

Clarke wrote his father soon after the lethal exchange took place. His terse description captured some of the tense moments when he came under “flank fire from inaccessible rocks” 200 yards from the cavalry column.

With Cpl. Scott wounded in both legs, Clarke rushed to aid his comrade. He told his father: “I had some close calls while I was trying to pull the corporal from under fire and succeeded in getting him behind a bush and you can be sure it was a very new sensation to hear the bullets whiz and strike within six inches of me and not be able to see anything.”

The lieutenant went on to observe: “Our men were played out to begin with and from the position we were in all of us would have been struck….”

Despite the desperate situation, the troopers held their ground. Clarke concluded, in a letter to his mother, “The wounded Corporal has had to have his leg cut off…. This man rode seven miles without a groan, remarking to the Captain that he had seen forty men in one fight in a worse fix than he was.”

The gravely injured, stalwart soldier was forced into medical retirement, while his rescuer, Clarke, was singled out for his daring deed. After five years, the slow wheels of bureaucracy led to the shavetail’s bravery being recognized by the Medal of Honor.

Aftermath: Odds & Ends

Geronimo continued to strike on both sides of the U.S.-Mexico border, killing dozens of civilians before finally agreeing to meet Gen. Nelson Miles. He accepted Geronimo’s surrender at Skeleton Canyon, in September 1886.

Powhatan H. Clarke continued his work in the field. He received another citation for conspicuous gallantry, this time for chasing down some of the last Apache holdouts at Salt River in Arizona Territory, on March 7, 1890. And, on June 20, 1890, Clarke, along with fellow 10th Cavalry officer G.E. Stacks, co-commanded a special detachment of 30 White Mountain scouts near Rucker Canyon, on the trail of the Apache Kid.

During his Arizona years, Clarke went into garrison variously at San Carlos and at Forts Apache, Grant (his main quarter when Remington visited) and Thomas.

Recommended: From Cochise to Geronimo: The Chiricahua Apaches, 1874-1886 by Edwin R. Sweeney, published by University of Oklahoma Press, and The Apache Wars: The Hunt for Geronimo, the Apache Kid, and the Captive Boy Who Started the Longest War in American History by Paul Andrew Hutton, published by Crown.